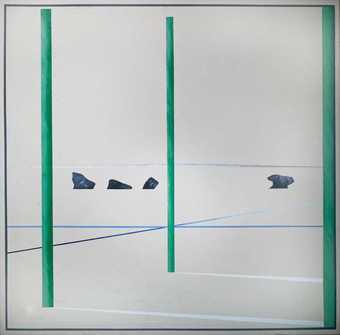

Derek Jarman

Avebury Series II 1973

Oil on canvas, 1219mm x 1219mm

© Estate of Derek Jarman, photo: Derby Museums and Art Gallery

In 1971 Derek Jarman made a 10-minute film called Journey To Avebury, documenting a summer walk through the chalklands of southern England. At first it seems more pastoral home movie than avant-garde artefact: sheep graze, footpaths dwindle into the long distance. Gradually, though, an eeriness builds. Where are the people? Who is holding the camera? The landscape feels emptied rather than empty. A psychic weather communicates itself to the viewer: close, clammy, threatening. Scenes part-repeat themselves, with inscrutable intent rather than by accident.

Vital to this unsettled atmosphere is the Super-8 film on which Jarman shot the work. Super-8 flickers and blebs. It bleeds. Colours thicken within it. Its scratchy textures suggest another set of frames underneath, showing through here and there: other stories trying to pry their way out, buried forces rupturing the surface.

After eight minutes, the film reaches the standing stones of Avebury. These are the upright sarsens (sandstone blocks) that form the site’s ceremonial henges. Hunched, silhouetted, organised – the stones appear alarmingly animate; dark figures shaken into movement by the agitations of the camera. Jarman’s film shivers throughout with suppressions: of power, of sense, of explanation. It is unsettlingly anti-scenic. Bucolic dreams of cultivation and consolation are disrupted. In place of the rural, the ruderal; in place of the serene, the eerie.

A tradition of eeriness runs through British art of the 20th and 21st centuries. It runs, though, not as an overground river might – with a traceable and continuous surface route – but rather as groundwater runs; surging out here and there, springing up at times of heavy weather. For this eerie art has often emerged at or after times of crisis, martial or fiscal: during the economic collapses of the 1970s and 2000s, or in the years around and during the Second World War. There is no mystery to this pattern. The eerie represents a counter-narrative to the recognisable traditions of the picturesque and the pastoral in British place-art. Where the pastoral encodes order and comfort, the eerie registers dissent and unease. It is drawn to what Christopher Neve memorably called ‘unquiet landscapes’, and it is born of unquiet times.

The etymology of the word eerie is appropriately unclear. It materialises first in Middle English (eri, hery) to mean ‘fearful’, then gathers a specific sense of sourceless unease, malingering dread. The eerie is alarming because its cause can rarely be explained or even detected. This sourcelessness distinguishes the eerie from the horrific, and is also the reason that eerie art – like eerie literature (MR James, Algernon Blackwood) – deals often in glimpses, tremors and forms of failed detection or observation technology (binoculars, tape recorders, notebooks, radar, sound mirrors). The eerie is monstrous precisely because it will not demonstrate itself (to demonstrate, from the Latin demonstrare, meaning to show or reveal).

Alan Reynolds

Keeper of the Dark Copse II (1951–2)

Tate

In Alan Reynolds’s remarkable painting Keeper of the Dark Copse II 1951–2, for instance, it takes the viewer time to perceive the pale standing figure among the black trees – and longer still to notice the larger dark figure stood behind and to its right. ‘Copse’ swells into ‘corpse’; shadows set the imagination skittering; questions proliferate. Who is the keeper, what does he guard and on whose authority? What casts the cruciform silhouette across the foreground – and then, how can it be a shadow, given that the light source is at the back of the painting? I am reminded of Iain Sinclair’s description in his 2015 book Black Apples of the Gower of a moment walking in west Wales when he imagined he witnessed, heart-stoppingly, that the shadows of trees and buildings were falling towards the sun, such that they seemed to ‘precede the structures to which they belonged’.

Certain key preoccupations are visible in modern British eerie art, returning across the decades (tropes as revenants). These recurrent motifs include trees, crops and foliage (especially elms and oaks); stones (often standing); fields and woods; dark humanoid figures (usually still, sometimes cowled); running men (often fleeing an unspecified pursuer); power sources (in terms both of energy and of authority); recording and surveillance devices; agents that see but are not seen; camouflage and militarism; relics and burial; and abandoned infrastructure. Its aesthetics include tangled undergrowth and the cross-hatch of branches, textures of fray and decay, echoes, hollows and shadows, concrete, bark and skin, skeuomorphism and mimicry. Intuition is preferred to positivism, mirage to transparency, repetition to progress. The best of this art is astonishing, and the worst is woo-woo. All of it is animated by an understanding of landscape as a site of contest rather than of comfort.

Paul Nash

Monster Field 1938

Photograph

17 x 30 cm

Photo: Tate © Tate Archive

As often, Paul Nash was a pioneer. His 1938 series of black-and-white photographs, Monster Field, documents dead oaks that have crashed to the earth. Supine, their branches resemble fingers and their trunks arms: to Nash, these forms possessed what in 1937 he had called ‘the mysticism of the “living animate”’ (to the pop-gothically minded contemporary viewer, they might also recall the Addams Family dismembered hand, dragging itself across table-top and floor). Around the same time that Nash was photographing his monstrous field, Edward Burra was beginning his fascination with cabbages: vegetables that bulge and distort in his canvases until, in Giant Cabbages 1970–1, they have become extruded, tumescent, hostile. Eileen Agar’s undated photograph of foliage, taken from a subservient position looking upwards at huge gunnera leaves, also figures a mutatedly powerful vegetable force, as do many of Graham Sutherland’s tree works. All of these images feature a damaged nature, repressed but returning – malign in consequence if not in intent.

Christopher Neve, writing with typical excellence on Burra, observes that the landscapes the artist painted in the last 15 years of his life (1961–76) were ‘odder and more potent than anything else he did’. Their power to disturb is unmistakable, but hard to articulate. Valleys twist into tightness; vanishing points first lead on and then engulf the eye. Hillsides are flensed by mining, or incised by river-cuts. Human presences are pale labouring ghosts (Sugar Beet, East Anglia 1973) or hooded black wanderers (Black Mountain 1968). From 1965 onwards Burra’s sister, Anne, would drive him to lay-bys with long views across moor or valley or field. Burra would sit and watch for hours, in silence. ‘He watched the countryside as though craving extremes,’ writes Neve, ‘and painted it as though something terrible were about to happen… Burra shows us a distraught countryside, never limited by its usual benign appearance, in the hope that we may be unsettled enough to have some feelings of our own.’

Reynolds’s paintings of the 1950s also confront and confound the bucolic-benign. Summer: Young September’s Cornfield 1954 clearly invokes Samuel Palmer’s crop paintings, but where Palmer presented scenes softened by moonlight and shadow, Reynolds’s fields are all spike and jag: pincushion teasels, caltrop corn ears and darting thorns. Their sharpness blades the eye; agriculture feels a temporary imposition on a self-willed landscape.

George Shaw’s recent enamelled edgelands are differently distraught from those of Burra or Reynolds. He shows us unpeopled playing fields, or strips of weed-strewn tarmac running between garage lock-ups. Sutherland’s pollarded riverside willows return as Shaw’s municipally lopped sycamores in estate-fringe woodlands. Bonfires and graffiti assume the status of ritual marks, alluding to ceremonies past and to come. ‘For the most part,’ writes Shaw, ‘these painted sites remain dark and the intentions of their creators obscure.’ Where his canvases thrive on emptiness, Joanna Kirk’s vast and intricate pastel works intensify detail towards the point of incomprehension. In The Battle of Nant y Coed 2013, for example, interlaced branches disperse and disrupt the gaze – again, it takes time to notice the figure among the weft: a young boy staring back at the viewer from the deep blue hue of the pastel.

Jeremy Millar

XDO XOL (film still) 2014

HD video/stereo, 48min 21sec

© Jeremy Millar, commissioned by Whitstable Biennale 2014

In film, I think of Jeremy Millar’s XDO XOL 2014, of Dan Walwin’s escape-and-evasion sequences, or of Ben Rivers’s Two Years At Sea 2011. Hermits and fugitives populate these films: people either hiding out or fleeing, always for unclear reasons. Millar’s film is set in and around a derelict pillbox on an eastcoast saltmarsh. Louise K Wilson’s video A Record of Fear 2005 was made on Orford Ness, the former nuclear weapons test site located on a shingle spit off the Suffolk coast. Rust-slurred concrete, decaying laboratories, Cold War listening stations and the pounding North Sea: the Ness feels like a stageset co-designed by Turner, Ballard and Tarkovsky. The photographer Jason Orton has also been drawn to the North Sea coasts, especially the Essex littoral, in his study of what he calls ‘the new English landscape’. His photographs imply invisible networks of surveillance and presence. A white horse stands spookily still behind a fence; massive concrete defences protect the coast against attacks from the sea or from an unspecified enemy. The eerie also flickers fascinatingly through recent digital art, especially that working in and with the sense of unease from our interactions with the not-quite-human, what has been called the ‘uncanny valley’ (itself an interestingly topographic term for a purely affective phenomenon). The artist Ed Atkins has mapped his own physiognomy on to the features of a standard avatar, who then represents him on screen: disturbingly close to, but skewed from, its human correspondent. His computer-generated imagery has a material counterpart in Millar’s Self- Portrait of a Drowned Man (The Willows) 2011. Millar cast his own body in silicone, dressed it in his own clothes, then gouged ‘his’ face and skull with odd puncture wounds, as occurs in Blackwood’s 1907 novella The Willows. The disconcertingly lifelike (deathlike) ‘drowned man’ that resulted was displayed prone on the gallery floor. First shown at Glasgow’s CCA, it proved so unnerving to audiences that advance warnings had to be issued.

George Shaw

The New Houses 2011

Humbrol enamel on board, 560mm x 745mm x 50mm

© George Shaw, courtesy Wilkinson Gallery

Jon Rafman’s ongoing 9-Eyes project exhibits a series of stills retrieved from Google Street View footage. Many are severely disquieting. In one, a cow drags its broken back legs across a highway towards a bloody yard. In another, a pair of seemingly identical twins walk with identical gait along a river shore, seen from a bridge; the shadow of one figure is impossibly truncated. Is it a glitch of the ninelensed (nine-eyed) car-mounted camera that Google uses to harvest its footage – or an uncanny doubling in real time? Shorn of explanation or outcome, these images exist in strange suspension, at once static and unsettled. Faces and data are often pixelated out, in keeping with GSV’s pseudo-privacy policy, to create floating spectral blurs.

The Rafman image to which I find myself most often returning shows what I take to be a roadside vineyard, somewhere in Europe. But there appear to be two plumes of smoke rising in the background, perhaps over the horizon, and the view is largely hazed out. The vines themselves are blackened and contorted: they resemble ranks of clutching hands, thrust up from the earth. It has the feel of a seared scene of post-apocalypse – or a digital re-take of one of Nash’s Monster Field stills, almost 80 years on. The rhyme between these two images, and the other patterns of connection that shimmer between the artists mentioned here, suggest that there exists a tradition of eerie modern art perhaps as rich as that of the pastoral – and certainly far stranger.