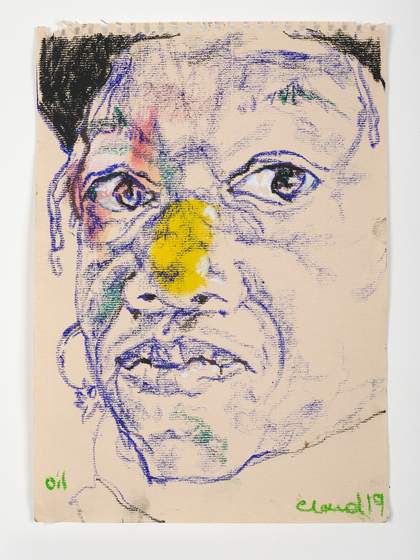

Delaine Le Bas’s layered installations interweave paintings, collages, costumes, soundscapes and performances. Her work explores ’un-painting’* her British Roma heritage and stories of her own life as well as feminist mythologies and herstories.

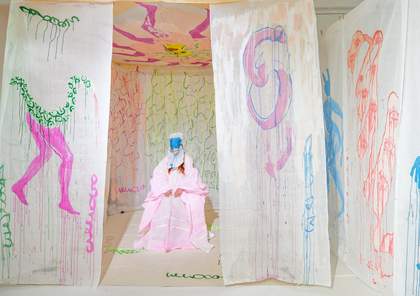

Le Bas has transformed her Turner Prize rooms into an immersive environment, splitting the galleries into corridors and small spaces. The artist uses a variety of materials to offer access points into her art. Organdie, calico and reflective foil cover the walls, floors and ceilings. Painted fabrics and sculptures sit alongside personal items she has remade. Le Bas says, ‘I’m interested in creating different doorways. The fabric is another way of engaging with people because it’s not behind glass … you are physically in the same space as it.’

Le Bas takes us on a journey through a psychic landscape, from chaos to reflection and, ultimately, a transformation. First, we encounter Marley, a hanging ghost inspired by the character created by Charles Dickens. Le Bas asks, ‘How can you make art in chaos and when someone is dying?’ The artist started making the work when her Nan was ill and her family life was in chaos, so it is infused with her memories of this time. A horse, stuffed with hay, is modelled on her Grandfather’s black china horse. The red boots underneath it are enlarged replicas of her first shoes. The horse and the original baby shoes were permanently on display in her Nan’s glass cabinet. Finally, painted footprints lead us to the ancient Greek priestess Pythia. Pythia, who guarded the Oracle at Delphi, asks us to confront and reflect, with the command ‘Know Thyself’.

Le Bas’s Turner Prize presentation is titled Incipit Vita Nova (Thus Begins a New Life). She says that’s what she wants people to take from it: ‘Many people at this moment in time and different parts of this planet … are not in a good place … they are in chaos and it’s terrible … you can be at that really dark place but then you can come out of it.’

*un-painting is a term coined by the radical feminist philosopher Mary Daly to describe a process that the Self must carry out. It is an expression of creativity and hope.

British Gypsy, Roma and Traveller Peoples

Gypsy, Roma (or the gender-sensitive term Rom*nja – the female plural term for Roma is Romnja) and Traveller are terms used in the UK to represent several ethnic groups that share certain common historical and social traits. The principal commonality is their history of nomadism. The umbrella term GRT is used officially by the British Government and Travellers’ rights organisations. The English word ‘Gypsy’ is often used in a demeaning way, but many people in the community use the term proudly.

Le Bas asks, ‘Who puts who in the boxes and who labels the boxes? … Who has the right to call who what? What rights do we have as individuals?’