I couldn't find images of us that I recognised. I could find lots of parodies of Black womanhood, so something new was needed, something that I felt was more authentic.

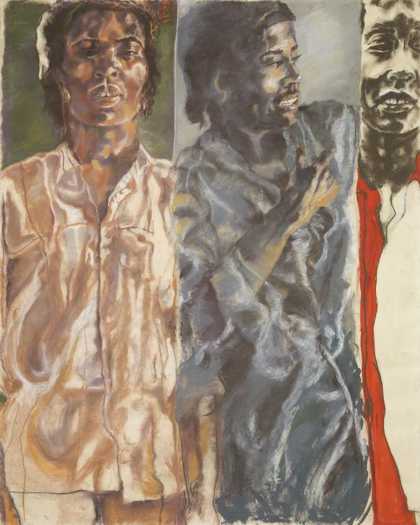

My name is Claudette Johnson. I'm an artist. I make large-scale drawings, usually of Black women, sometimes of Black men. I wanted to tell a different story about our presence in this country.

If I'm drawing from life, which is my preferred way, I almost always start with the head, with the forehead and cheek. I don't know why. Usually, by the end of the drawing, I've had to revise that because it's been wrong, but it’s a place where I start.

It's easier for me to work with people I have some kind of prior contact with. I think there was a point when I was almost looking for a particular set of features or particular angles. In more recent years, that hasn't been so important to me. The relationship has been more important because, as I say, I want to be able to get close enough to project the presence of this person. And it does feel like collaboration.

When I made my first series of work in my final year at Wolverhampton, I hit on something. I thought, Ah, this is what I do. This is where I go. I wanted to get away from the spectrum that's most respected here in, let's say, European painting.

Kind of Blue is the work that's based on a photograph I saw by a South African photographer called Peter Magubane. I'd always loved the face of this adolescent boy who's featured in his work, so I've transplanted him to a blue colour field. And again, the blue just got bigger and bigger as I made the work until it was practically three-quarters of the work.

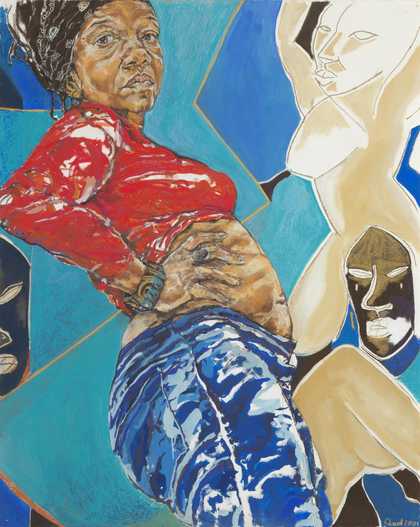

Standing bigger with African masks, it does refer to the Demoiselles d'Avignon by Picasso. The first time I saw it, I thought, Wow, those women are just not to be messed with. These are women in their power, and that's what I wanted to take from it. As well as a reappropriation of his appropriation, in the sense that I've been trying to understand my relationship to African art. I wanted to bring his women in, but my version of his women. I was going to call it Call of the Ancestors because the figures alongside her, I feel, are ancestral presences. She's negotiating a relationship with them, and I still don't know exactly what that relationship is.

Being the '80s, there was a whole movement of collective building. We were part of that moment where everyone understood how powerful it was to work, to join with other people, to try and make your voice heard. What was then the Wolverhapton Young Black Artists became the Black Art Group. We were all making work that was about the experience of being Black and British in the '80s. There was quite a strong political focus, and so it chimed with some things that I was doing in my own work. I was really pleased to come into the group and then help to organise a conference that we held in Wolverhampton in 1982, the first National Black Artists Convention.

We couldn't assume that institutions were going to be interested in what we were doing, and we had to make our own spaces for that. It felt like this ground swell of energy, which was carrying us forward.

Some of my influences are authors like Toni Morrison, who was an African-American author. Key work for me was The Bluest Eye. There's a passage in that book where she describes an encounter between the central character, Pecola and a shopkeeper. Because Pecola is Black, poor and not pretty, it's impossible for the shopkeeper to actually register her presence in any significant way. He can't really see her, so to all intents and purposes, she is invisible. And that chimed for me.

As a child here, I can remember sitting on a bus, my seat being the only one that was empty on a wet, rainy day in Manchester. The bus was crowded, people were getting on, but the only space that was available was next to me. I was a child. This woman did not want to sit down beside me. Maybe she had some other reason, but I felt it was this issue of not wanting to be up against a Black person. Certainly, being in art college and being in such a minority didn't feel unfamiliar. It didn't surprise me. So, in a way, I almost had to reverse it and think about what it was like being in a space where there were mostly Black people for the first time to understand what I’ve been negotiating all these years.

That experience was going to Jamaica. I was almost overcome by how people were with their bodies in the space. There was no fear or revulsion about skin brushing against each other. It was so liberating, so new, this sense of my body not being contaminating, being liberated from that sense, was extraordinary.

There's something quite powerful about just giving space to the presence of a Black woman. Something that's quite hard to define, but it's about trying to offer something that maybe somebody may have missed, this, this presence. I don’t know if that gets anywhere near it. It's so hard to define.

My name is Claudette Johnson. I'm an artist.

Artist Claudette Johnson uses painting and drawing as a means to explore representations of Black women (and sometimes men). Johnson's subjects are people she knows well, often drawn from life; a process which allows her to project the presence of the person she is drawing. Each large-scale artwork boasts a rich colour palette. Completed at the time of filming is her most vibrant yet, Kind of Blue, which features throughout the film.

Claudette Johnson is nominated for the 2024 Turner Prize, hosted by Tate Britain. The winner will be announced on 3 December 2024.