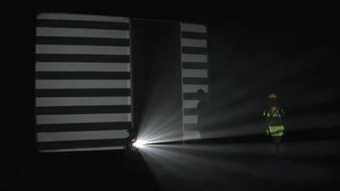

Photo: © Laura Cugusi 2019

London based Sophia Al-Maria has created Beast Type Song by weaving together music, literature, oral history, film and dance. It is a film that is based on personal heritage and how one's identity changes and adapts according to the way history is told and revised.

A series of protagonists, including Al-Maria herself, reflect on the narratives and languages they have inherited as children of various colonial legacies. Beast Type Song considers how violence impacts the body but also invites us to consider how storytelling can be a violent act with its own consequences.

What is Beast Type Song?

A lucid dream.

Where does the title come from?

That is a secret, but hint: the acronym is significant.

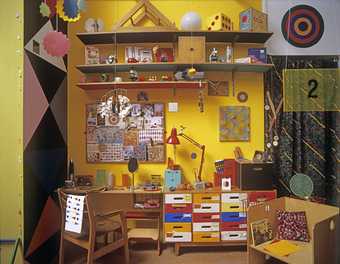

Sophia Al-Maria, Beast Type Song 2019 Photo: © Tate (Sam Day)

Sophia Al-Maria, Beast Type Song 2019 Photo: © Tate (Sam Day)

What interested in you in these stories?

The stories in the film accrued. I did not collect them. I wanted it to remain malleable without a fixed order – like a documented dream. The songs, the found footage, the snippets of text, the arrangement of scenes, the voice notes from mothers, the moments of eye contact with the camera – these were all gathering and landing of their own accord. Like the research process – the making was a derivé.

So much of the beauty in this project came from conversation and correspondence and chance encounters with the people I was collaborating with. For example, Yumna’s kinship to the poet Ghassan Kanafani only came up chatting late into the night. Similarly, the casting of Elizabeth was serendipitous. Without having any idea where we were going with the conversation, we ended up talking in depth about mother tongues (in her case Igbo) and our shared interest in the poet and activist Ken Saro Wiwa. Another example is that I was reading the essay on Battle of Algiers, which is included in the film, and on the same day a correspondence came from Farida Khelfa and I was tremendously amazed at her generosity in translating and reading the text. Patterns started to emerge – of language, of assassination, of politics and poetics, and creation, and destruction, and what the future might bring should we remain trapped in a certain war with words. Words – which I was and am becoming increasingly mistrustful of when forged into blunt meaning objects called complete sentences.

This is why poetry came to my rescue. When I began to read Etel Adnan's The Arab Apocalypse, the character of the solar war veteran with her tongue cut out came into mind. And because boychild’s work so brilliantly articulates what is felt but cannot be said and pushes at what kind of expression is possible without words – I asked if she would take this role in the film and then finally the vessel was full and Beast Type Song was sung.

Sophia Al-Maria, Beast Type Song 2019 Photo: © Tate (Sam Day)

How did it feel being in front of the camera telling your own story?

Uncomfortable.

Sophia Al-Maria, Beast Type Song 2019 Photo: © Tate (Sam Day)

Could you tell us more about the poem, The Arab Apocalypse, that you have used as a foundation for the piece?

When I began reading Etel Adnan's poetry (only this year!) – I had a profound sensation of return. It really was as if I’d wandered a very long way only to find myself in the motherland I had forgot. I had been given her books, people had spoken to me about her, I vaguely knew of her painting. But reading the first lines of The Arab Apocalypse – it felt like a return from exile. As if I had found the foundations of a home I had lost and could build from.

I had given up on writing after the brutalism of doing it for commercial television. The way in which Adnan struggles against language through gesture, through trying to learn a new language later in life, not to mention the uniqueness of her person and lived loves in life – these are not small feats of grace. This is why the film is dedicated to her.

Sophia Al-Maria, Beast Type Song 2019 Photo: © Tate (Sam Day)

Shakespeare’s The Tempest is referenced throughout the film. What does this play mean to you in the context of your film?

Chance was and is my guide. And really the wreckage of another project ended up washing me up on the shores of Shakespeare. This isn’t a surprise I guess, because of his outsized influence on the English language. Love poetry, fantasy and narrative structure in western drama - these are all subjects I can definitely say are the root material of what the dream is about. I think the thing which brought me to The Tempest originally was Prospero declaring 'I’ll drown my books', because I had become so disillusioned with writing. Then I came to read about the Algerian witch, an unseen and unspoken character – Sycorax. And her adoption in post-colonial studies as the silenced ‘other’.

Is there an overall feeling or thought you would want your audience to have when seeing the film?

Speechless. With an overwhelming urge to make some noise.

Sophia Al-Maria, Beast Type Song 2019 Photo: © Tate (Sam Day)

Art Now: Sophia Al-Maria Beast Type Song is on at Tate Britain until 23 February 2020.