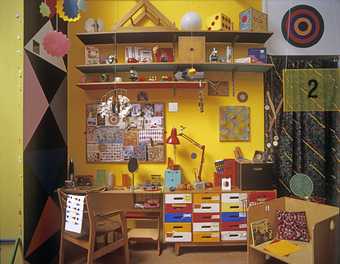

Chapters One to Five, 2012, Production Still © Sophie Michael

Where does the title of your exhibition Trip (the light fantastic) come from?

When I was in Devon shooting my latest film, The Watershow Extravaganza 2016, I flicked a particular switch behind the scenes of the organ by accident and tripped the circuit causing the whole show to go out of sync. That got me thinking about how all of the works in this exhibition involve some kind of tripping of light and sound. Within each film sound and image is choreographed to constantly move in and out of sync – like a sort of dance sequence. To 'trip the light fantastic' means to dance nimbly on your feet.

Trip (the light fantastic), 2016, Install shot © Tate

How do the three films relate to each other, notably the relationship between abstraction and figuration?

The three films shuttle between abstraction and figuration, albeit Chapters One to Five 2012 less obviously. But for me it's mostly to do with their approach and tone. All of the works dance lightly around potentially heavy subject matter or try to make light of a situation. It has something to do with performing innocence, and a relationship with the past which is distant and ambiguous.

How did you start working with 16mm film?

I studied at Slade in the Sculpture department, and arrived at film only in my final year of the BA after experimenting with 35mm slides. I would still say that I am a sculptor who makes film. When I got to the Royal Academy Schools for my postgraduate I built installations based on 1960s and 1970s home improvement manuals and educational films. I spent months collecting and arranging objects in one space, and these spaces inevitably became sets.

Chapters One to Five 2012 Courtesy of Sophie Michael, Seventeen Gallery © Sophie Michael

How did you come about 99 Clerkenwell Road 2010, the only silent film in the exhibition, and the most abstract of the three?

I made this film in an empty shop. At the time I was watching a lot of Oskar Fischinger films on mute, visual music minus the music, with silence as an alternative soundtrack. Although 99 Clerkenwell Road is the only silent film in the exhibition, silence constitutes the soundtrack and should be perceived as a presence rather than an absence.

What impact did the architecture of the space have on the process of making the film?

I made the animation using the few elements left in the space - the spherical lights as shapes, pillars as masks and shop shutters as stencils. Most of Fischingers' films occupy a flat space, so in this film I wanted to begin on a similar 2D plane then slowly reveal the 3D elements of the shop's architecture.

I made the elements move by tilting the camera up towards the ceiling, using coloured glass filters over the lens and a dolly to drive the camera around. Because I was looking up into the viewfinder as I was filming, it was difficult to see what was in my path, so sometimes I would bump into a pillar or wall and that would be the end of the shot. Being 'blind' and chance played a big part in the making. Another way in which I let the process take over was using multiple exposures in-camera.

99 Clerkenwell Road, 2010, 16mm Film Still © Sophie Michael

Can you explain how you worked on this process of multiple exposures?

I composed it almost like a piece of music that starts off quietly and finishes with a visually noisy climax. I began with one exposure, then gradually added a second, then third, ending up with five or six layers towards the end. I always roughly log the frame count on paper so I can look back and see the points at which I rewound the film to each time. I also noted colours and directions of movement. The log looks a bit like a score.

Do you apply the same process to all of your works?

Technically speaking, the Astrid series is very different. With the exception of those works I use the process of layering exposures time and time again. I used it in the second half of The Watershow Extravaganza, with the addition of a matte box to block out parts of the image. But in another way the films with Astrid are not so different, because she is the substitute for in-camera effects. I can't control her will any more than I can control what goes on inside the camera! In all of my work there has to be some unpredictable elements, a double authorship, a point where I relinquish control of the process and the film takes on a life of its own somehow.

Trip (the light fantastic), 2016, Install shot © Tate

Is the bus in 99 Clerkenwell Road one of these unpredictable elements?

I’d say the bus was the happiest accident in this film, because it completely shatters the illusion of flatness. It also stops the work from being a rigid structuralist film straight out of the 1970s, which I have a love hate relationship with. I love colour, light, materiality of 16mm and admire its stubbornness not to break its own rules.

How do you situate the medium of 16mm film in the digital age we live in?

I’m interested in the anachronism of using 16mm today, in the same way that I am curious about how Astrid responds to a period which neither I nor she grew up in. Both are out of place and time but what I am interested in is how different generations get cross-wired in the now. Most of us have some level of familiarity with retro objects and analogue film paraphernalia that relates to our lives now. A piece of repro- furniture represents an approximation that children refer to as ‘The Olden Days’ – a sort of Instagram fantasy. 16mm has taken on that meaning now. I wanted to make the work look as if it could have been found in someone’s attic, that the girl in it might now be in her 50s.

The Watershow Extravaganza 2016, Courtesy of Sophie Michael © Tate

Is this artificial anachronism the subject of your new film, The Watershow Extravaganza?

Part of the reason why I was so drawn to the Watershow attraction was because it is cobbled together using parts from different decades throughout the 20th century, from the 1920s paper roll organ, to the 1952 water tray to the 1970s mechanical clapping hands, to the 1980s fake plants. I suppose the idea of ‘retro’ is common to every time, and it just keeps building up layers on layers to make the present.

Looking back at those past moments in time creates a sense of nostalgia in your work.

I think it is important that the films layer and stretch time in an attempt to get closer to an idea of the present. It’s important that the films are self-contained in their own miniature worlds, and that characters or objects are detached and solitary. Astrid plays alone, as I want to indulge this sense of nostalgia. I hope the viewer might even project onto her.

The Watershow Extravaganza, 2016 © Sophie Michael

Could one see in The Watershow Extravaganza an analogy between analogue film and the mechanical organ?

There are a lot of synesthetic connections in the film that are to do with mixing film grain and water to the point where you can’t tell them apart. I really enjoy how the film fuzz and water droplets to dance together on the surface of the film, and the projector purr gets absorbed in the low water fuzz.

Is this intended to be a celebratory film then?

Not exactly, I think the tone is bittersweet. The Watershow is relentlessly playing the national anthem, waving its flags, demanding applause but its original audience has grown up and it is too old to reach the top notes or fountain positions. There’s no doubt it is spectacular, but at the same time the patriotic climax now seems naïve, out of date, tragic.

Trip (the light fantastic), 2016, Install shot © Tate

Art Now: Sophie Michael Trip (The Light Fantastic) was exhibited at Tate Britain until 30 October 2016.