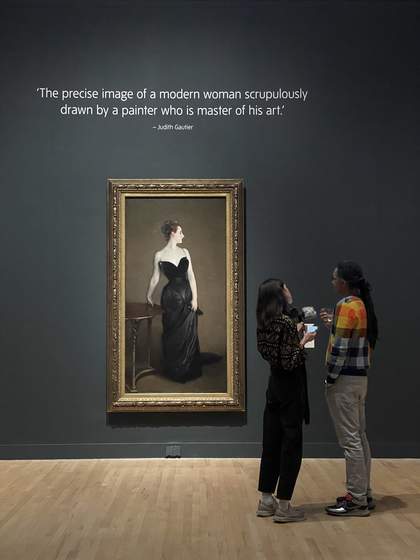

Kimathi Donkor and Jelena Sofronijevic recording in front of Madame X at Tate Britain, 2024

The Tate Interpretation team invited five contributors to tour the exhibition and respond to a number of John Singer Sargent’s artworks. They provided responses based on their expertise and lived experiences, as well as personal and familial connections to the works.

You’re invited to listen to the audio tracks below and to consider the power of fashion and how it can make us reflect on our lives, identities and positionalities.

LADY SASSOON

Sargent and Fashion, Installation View at Tate Britain 2024. Photo © Tate Photography (Liam Man)

Listen to art historian Richard Ormond talk about the way Sargent manipulated fashion to paint this portrait of Lady Sassoon.

MADAME X

Sargent and Fashion, Installation View at Tate Britain 2024. Photo © Tate Photography (Recce Straw)

Listen to artist and academic Kimathi Donkor discussing the hidden legacies of imperialism within Sargent’s portraits of Virginie Gautreau.

MRS FISKE WARREN

John Singer Sargent, Mrs Fiske Warren (Gretchen Osgood) and her Daughter Rachel 1903, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of Mrs. Rachel Warren Barton and Emily L. Ainsley Fund

Listen to art historian Richard Ormond talk about the experience of sitting for Sargent.

‘WONDERFUL POSSIBILITIES’ (ROOM 4)

Sargent and Fashion, Installation View at Tate Britain 2024. Photo © Tate Photography (Liam Man)

Listen to journalist and novelist Tom Crewe discuss Sargent’s work and queer Victorian life in 1890s London.

W. GRAHAM ROBERTSON

John Singer Sargent, W. Graham Robertson 1894, Tate. Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1940

Listen to journalist and novelist Tom Crewe respond to W. Graham Robertson’s portrait and discuss the tensions between private life and public persona.

MRS CARL MEYER (ADÈLE LEVIS) AND HER CHILDREN

John Singer Sargent, Mrs Carl Meyer (Adèle Meyer) and her Children, Frank Cecil and Elsie Charlotte 1896, Tate. Bequeathed by Adèle, Lady Meyer 1930, with a life interest for her son and grandson and presented in 2005 in celebration of the lives of Sir Anthony and Lady Barbadee Meyer, accessioned 2009

Listen to teacher and curator Tessa Murdoch’s response to this family portrait of her great grandmother Adèle Meyer and her children.

Indian Shawls

Detail of: Unknown maker, Shawl c.1908, Private collection

Suchitra Choudhury is an expert in English postcolonial literature associated with India. Listen to her reflections on the use of Indian shawls in Sargent’s paintings.

Cashmere

John Singer Sargent, Cashmere c.1908, Private collection

Suchitra Choudhury is an expert in English postcolonial literature associated with India. Listen to her reflections on the painting Cashmere.

The Chess Game

John Singer Sargent, The Chess Game 1907, Allen Family Collection

Suchitra Choudhury is an expert in English postcolonial literature associated with India. Listen to her reflections on the painting The Chess Game.