George Grosz

Grauer Tag (Grey Day) 1921

Nationalgalerie Berlin

© DACS, 2018

Introduction

Aftermath explores the impact of the First World War on the art of Britain, France and Germany between 1916 and 1932. More than 10 million soldiers died and over 20 million were wounded during the war, while large areas of Northern France and Belgium were left as ruined wastelands. The exhibition explores how artists processed the physical and emotional effects of this devastation.

The First World War was a global event, with fronts in Africa, Asia and Europe. Aftermath does not attempt to give a complete picture of the conflict but looks at its role as a catalyst for major developments in western art. It centres on the art worlds of Berlin, London and Paris.

The shared experience of loss and destruction inspired divergent artworks. Aftermath encompasses depictions of landscapes after battle, war memorials and reflections on post-war society. Works include personal meditations and official commissions. Some artists looked back to earlier art forms to create scenes of longed-for harmony and regeneration. Others pushed art in new directions to represent bodies and minds fractured by war.

The First World War also touched the lives of millions of people who did not experience battle first hand. ‘Aftermath’ was originally an agricultural term meaning new growth that comes after the harvest. Society as a whole was reshaped in the years that followed the war. Artists reflected on the social and technological changes with anxiety and optimism.

Room 1

Remembrance: Battlefields and Ruins

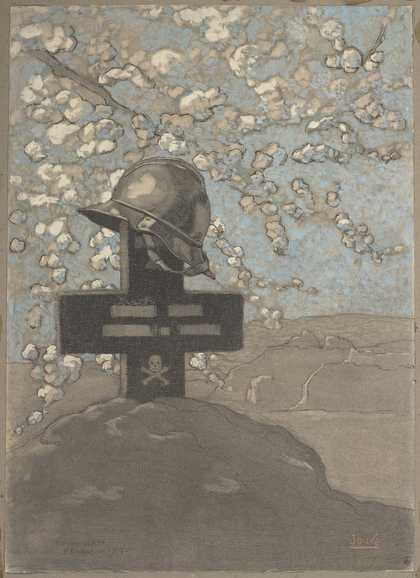

Paul Jouve

Tombe d'un soldat serbe à Kenali 1917 (Grave of a Serbian solider at Kenali 1917)

Musée de l'Armée (Paris, France)

During the war, artists were already creating works reflecting on its impact. Many of the artists whose work is in this room saw military service. They struggled to show a civilian audience what they had experienced. In depictions of battlefields, the loss of human life is indirectly expressed by mud, shell craters and broken trees. These scenes evoke the silence and absence once the fighting has stopped, but also signal the violence that came before. After the war, ruined towns and battlefields became sites of pilgrimage, documented in guidebooks and postcards.

Heavy artillery and automatic weapons resulted in a previously unimaginable death toll. Some artists tried to communicate the scale of this loss while others focused on individual tragedies. The abandoned helmet became a poignant symbol of a single soldier’s death shared by British, French and German artists. Artists who showed the brutal realities of conflict more directly sometimes experienced state censorship.

Governments also shaped visual representations of the war to different degrees. Britain launched an Official War Artists Scheme in 1916 which commissioned artists to create eye witness images of the front line and home front. Also in 1916, France established a ‘Mission aux armées’ which allowed artists to visit the front at their own expense. German artists could apply for a private permit to visit the front line.

Room 2

War Memorials and Society

Ernst Barlach

Der Schwebende (The Floating One) 1927, cast 1987

The armistice of 11 November 1918 declared the end of the war. Ceremonies of communal mourning promoted unity in the times of social and political unrest that followed. In July 1919, Britain and France marked the end of the war with public processions. Both used an empty tomb, or cenotaph, as a focus for national remembrance. The tomb of the unknown soldier specifically commemorated the absent and unidentified dead.

These memorials were inaugurated in London and Paris on 11 November 1920. The end of the war and the culture of commemoration were disputed in Germany. No national memorial existed until 1931. Instead, individual cities commissioned their own memorials. Local monuments were also erected in France and Britain, giving communities a site for remembrance. In the military cemeteries in France and Belgium, memorial sculpture marked the sacrifices of men in all three armies.

Architectural memorials such as the Cenotaph were deliberately abstract to represent all citizens. Memorial sculptures included both symbolic figures and detailed representations of contemporary soldiers. These predominantly depicted white bodies. There were few official memorials to the servicemen from Asia, Africa and the Caribbean who served with the British, French and German armies.

Room 3

Traces of War: Wounded Soldiers

Otto Dix Prostitute and Disabled War Veteran. Two Victims of Capitalism 1923

LWL-Landesmuseu

Soldiers’ wounds represented an alternative memorial, visible in flesh rather than stone, and a reminder of the terrible cost of war. Disabled veterans in all three countries struggled to resume the lives they had led before military service, but were represented in very different ways.

During the war the skills of artists were in demand to record the work of military hospitals and in Britain soldiers’ war wounds were rarely depicted outside a medical context. The visibility of men with facial injuries – in daily life and art – was particularly sensitive. In France disabled veterans were highly visible. They attended the signing of the peace treaty at Versailles and featured prominently in the commemorative events in 1919. The campaigning of the organisation Les gueules cassées (‘the broken faces’) ensured their continued prominence in the 1920s. In Germany, images of wounded or psychologically traumatised men circulated widely in anti-war literature and art. Artists such as Otto Dix and George Grosz criticised post-war German society by showing the marginalisation and mistreatment of disabled veterans.

The language and definitions of disability have changed significantly over the last 100 years. The titles of several works in this room include words that are now recognised as offensive. The term ‘cripple’, used to identify someone with a physical disability, was commonly used in the early twentieth century without the negative connotations it holds today.

Room 4

Traces of War: Dada and Surrealism

Max Ernst

Celebes (1921)

Tate

Dada emerged in Switzerland during the war and soon became an international art movement. The artists involved felt the senselessness of the conflict called into question every aspect of society. Other groups, such as the surrealists, set out to destabilise conventional gender roles and social order. In the 1920s dada artists Hannah Höch and John Heartfield made collages that contested how the war was being remembered. George Grosz and Edward Burra depicted figures that combined flesh and machine parts. These echoed the use of prosthetic limbs by war veterans and evoked anxieties about the fragility of the male body.

War damage inflicted on bodies and particularly minds also shaped surrealist art and writing. Many soldiers suffered post-traumatic stress disorder, known at the time as shell shock or war neurosis. Symptoms included acute anxiety, paralysis and inability to reason and communicate. Surrealism channelled these symptoms in approaches that rejected rationality and conscious thought, such as Max Ernst’s irrational juxtapositions of images and the automatic drawing practised by André Masson.

Room 5

The Print Portfolio

The print portfolio was an important medium for artists in France and Germany commenting on the impact of the First World War. The format had an established audience in these two countries. Produced in editions of tens or hundreds, compact and relatively inexpensive, it had a broader reach than painting or sculpture. It offered the opportunity to create a narrative with a thematic set of images. It was also a medium that could be consumed at home rather than in the gallery, making it easier to present critical responses to the war that countered official propaganda.

Max Beckmann’s Hell series was made in 1919, during a period of intense political upheaval. It presents post-war Berlin as a violent and lawless society in chaos. Otto Dix’s The War encapsulates the horror of the trenches through shocking depictions of dead soldiers and shattered landscapes. Käthe Kollwitz’s War, one of the most powerful anti-war statements made in Germany, focuses on the war from the perspective of mothers and children. Georges Rouault worked on his series Miserere et Guerre (Mercy and War) for fifteen years between 1916 and 1931, adapting biblical imagery to reflect on contemporary experience. In it, he connects the population’s suffering with Christ’s agony on the cross.

Room 6

Return to order

Georges Braque, Bather 1925

Tate

Georges Braque © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018

Artists’ experience of the catastrophic impact of war often prompted a radical change in their work. Geometric and mechanised forms had been central to avant-garde movements before the war. Many artists turned instead to realism and traditional genres such as portraiture, religious painting and landscape. This revival became known as the ‘Return to Order’. But more than revisiting old approaches, it took realism in new directions, rendering everyday life with precision and clarity amidst a chaotic economic and political climate.

Classicism was used to align values of civilisation and tradition with national identity. Artists also depicted biblical stories in contemporary settings to reflect on the consequences of war. There was a revived interest in landscape painting in this period. Pastoral scenes reflected nostalgic longing for a time of peace before the onset of war, and unpopulated landscapes evoked the pervading sense of loss. Women’s roles had changed dramatically and contrasting imagery of maternal femininity and the emancipated ‘new woman’ presented different views of their place in post-war society.

Room 7

Imagining Post-War Society: Post-War People

William Roberts

The Jazz Club (The Dance Party) 1923

Leeds City Art Gallery

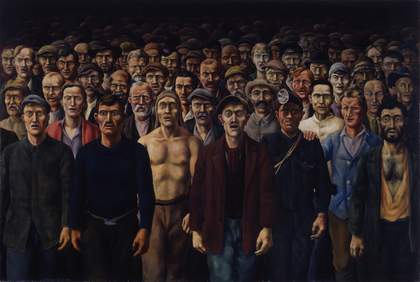

Social unrest and political upheaval were intense in the 1920s, particularly in Germany, where inflation and mass unemployment resulted in acute inequality. Many New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) artists tackled social themes from a political perspective. George Grosz’s Grey Day explores the impact of the war on a series of social types, suggesting that despite the upheaval society has reverted to its old class divisions. Artists also commented on the unequal fortunes of those who had stayed at home and those who had fought for their country. The figure of the profiteer who benefited financially from the war frequently provided a focus for social critique.

Urban society could be shown either as a hotbed of decadence and moral corruption or as a site for new opportunities. Many artists were committed socialists in this period and used their work to argue for a more equal society. The ordinary worker was often presented as a heroic figure. Jazz and dance culture swept London, Berlin and Paris as pleasure-seeking offered a release from the problems of daily life. In Britain and Germany many women were able to vote for the first time and their increased presence in the workforce also gave them greater economic freedom and independence in city spaces.

Room 8

Imagining Post-War Society: The New City

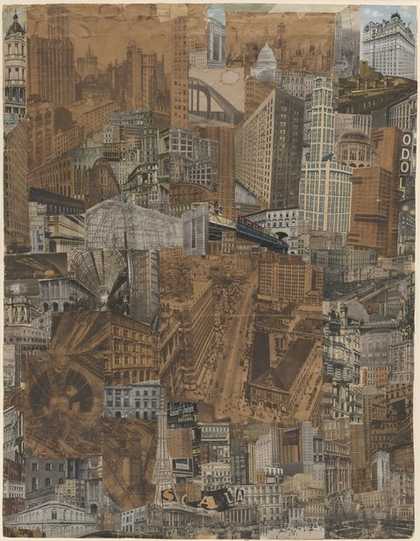

Paul Citroen, Metropolis 1923

Leiden University, Study Centre for Photography, Leiden Abb.S.9

Artists responded to the technological changes shaping and reconstructing the modern city with a mixture of hope and anxiety. In the 1920s many looked to the United States as an example of technical progress and modernity. The skyscrapers of New York feature in cityscapes by CRW Nevinson, Paul Citroen and El Lissitzky. Fernand Léger extolled the beauty of machinery and was fascinated by the automated production processes of American factories. The photomontages of

Alice Lex-Nerlinger present a less positive view of these new developments, showing workers becoming part of the factory machinery and subject to its relentless schedules.

The Bauhaus, a German school of art and design founded in 1919, aimed to shape the modern world by integrating art into society. Professors and students there imagined how the city might be transformed by new design and architecture. Bauhaus teacher Oskar Schlemmer’s abstracted figures offer a universal representation of humanity for modern times.