Douglas Gordon Pretty much every word written spoken heard overheard from 1989 2010

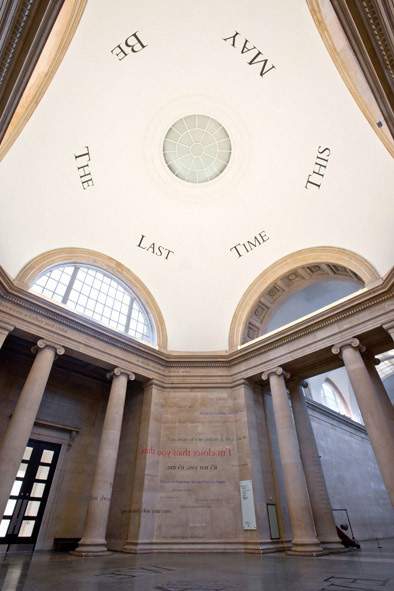

Douglas Gordon's work embraces a wide-range of media including video, photographic, audio and text-based works. A defining feature of Gordon's approach is an acute sensitivity to the associative power, whether actual or potential, of a particular site. In 2009, he was commissioned to create a site-specific work at Tate Britain, to be installed in the Octagon and alongside Art and the Sublime, a display of historic sublime works in the adjacent gallery. These spaces are remarkable for their austere, neo-classical grandeur, with barrel-vaulted ceilings and a central dome designed to make the gallery a 'temple of art'. Gordon's response was to utilise and animate the architecture itself with a complex yet cohesive installation of over eighty text-based works entitled Pretty much every word written, spoken, heard, overheard from 1989… 2010.

I always liked the idea that words, which are supposed to be concrete, when spoken by a different person at a different time can have a completely different meaning.

Douglas Gordon

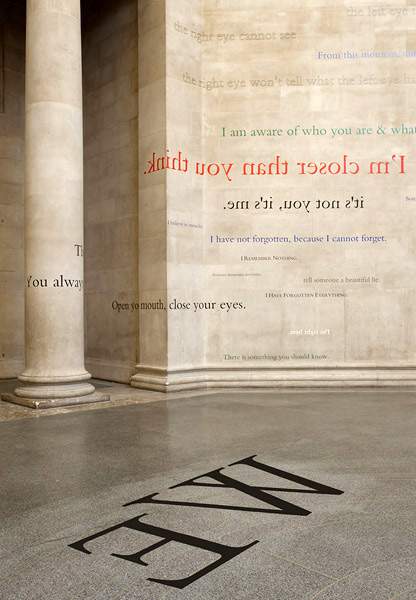

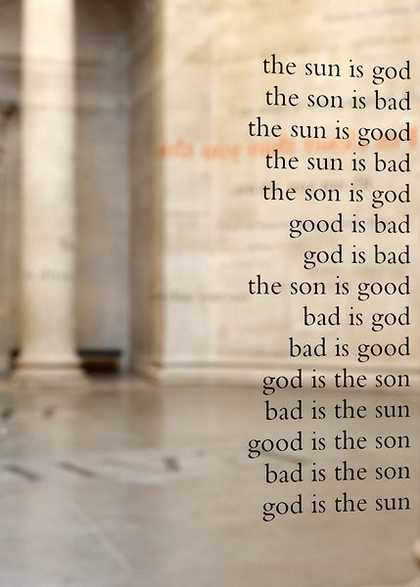

On one level, the effect seems to articulate Gordon's idea of art operating as 'a dialogue between artist and viewer', hence many of the texts address us directly, employing 'I', 'You' and 'We'. On another, it underlines the artist's fascination with language and its potential for ambiguity, obscurity and multiple meanings. As the title suggests, the origins and style of these texts are wide-ranging, both personal and universal. Some have a rhetorical or Biblical tone, such as the declamatory 'We Are Evil' on the floor of the Octagon, or the contemplative rendering of 'Read the Word…Hear the Voice' on the ceiling above the historic painting display in Gallery 9. The latter is positioned opposite, and thus in dialogue with, a text set as an ellipse that quotes one of the sayings of Jesus Christ, 'Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in paradise', spoken during his crucifixion, as related in the Gospel of St Luke (23:34) and here installed in powerful juxtaposition with John Martin's Last Judgement trilogy. The quotation is not, however, as straightforward as it first seems, hence Gordon's interest in it. Indeed, various translations of the Bible over time have changed the punctuation and thus the meaning, with the comma appearing either before or after the word 'today'. Will redemption come today or sometime in the future? Both interpretations are represented in Gordon's text work.

Douglas Gordon Installation shot from Pretty much every word written spoken heard overheard from 1989 2010

Douglas Gordon Installation shot from Pretty much every word written spoken heard overheard from 1989 2010

Douglas Gordon Installation shot from Pretty much every word written, spoken, heard, overheard from 1989... 2010

Others texts utilised by Gordon are from popular culture, including 'This May Be the Last Time' on the domed ceiling, a line taken from a song by The Rolling Stones (that was, in turn, adapted from a gospel song). Of course, the act of looking up into the dome takes us back to the literal meaning of 'sublime', that is, something 'set or raised aloft'. Indeed the dome itself has powerful cultural and spiritual resonances, being the signature feature of Byzantine, Renaissance and Baroque architecture and of temples, churches and mosques: a symbolic expression of religious aspiration. Gordon's words certainly look appropriately vast and oratorical thus chiming with the kind of authoritative inscriptions often employed in monumental interiors. But, given that it's a line from a rock song, is the artist challenging our expectations for appropriately elevated meaning?

The installation by Douglas Gordon and Art and the Sublime in Gallery 9 form part of The Sublime Object: Nature, Art and Language, a research project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, under the Landscape and Environment Programme.