David A. Ross

Both of you have worked in the medium of video, but starting in different decades and different cultural environments. For example, Peter, when you showed your video installations at the Bykert Gallery in 1975 there wasn’t much cable television. However, what you have in common is a deep and serious engagement with cinema. I know you are both fans of Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, a film that underscores the idea of looking, the psychological complexity of being looked at, the gaze of the camera, but also the obsession of recording and filming – all aspects that relate to both your bodies of work.

Douglas Gordon

One of the things I recognised when watching Peeping Tom again was a schism between Peter’s generation and mine – between the ways we received those images in the first place. Peter, you used to go to the movies, while I, like many of my generation, would lie in bed and watch television. We saw cinema through the conduit of television.

Peter Campus

We went to the movies as a family, twice a week at least. We had television, but it showed things such as Hopalong Cassidy. Did you like that programme?

Douglas Gordon

I was more of a Buck Rogers man… I think the socialisation of the way you receive things does make a difference, including, for example, who you’re in bed with when you see the film. And it is different again if you’re very small and watching TV in bed with your parents.

Peter Campus

We didn’t have a TV in the bedroom. It was still an odd thing, the focus of the living room. Our communal thing was going to the packed local movie theatres.

Courtesy Kölnischer Kunstverein

© Peter Campus

Douglas Gordon

The ‘televisualisation’ of cinema is a very important difference between my generation and your experience. Perhaps not a generational issue, but an experience issue. When the video recorder came along, it just so happened that Glasgow, where I was brought up, had the highest percentage of recorders per capita in Europe, because it had the highest unemployment under Thatcher. So the way that my generation would look at films was really interactive. There’s a difference between interaction and participation, and I think when you’re twelve years old watching Baywatch, you don’t understand the fine line between participatory action and Pamela Anderson walking along the beach time and time again, and in slow motion. Then I learned that there had been a previous generation who were looking at film frame by frame in order to exercise the desire for the truth of a movie. It was the same process, but with an entirely different motive. So when I screened 24 Hour Psycho in an art environment, it gave me a half-way house between the university and the bedroom. And wherever you watched it, the great thing was that you didn’t know who you were standing next to.

David A. Ross

Peter, what was it that led you to begin the exploration of the link between visuality as you experienced it as a filmmaker (and film viewer) and your interactive live video works?

Peter Campus

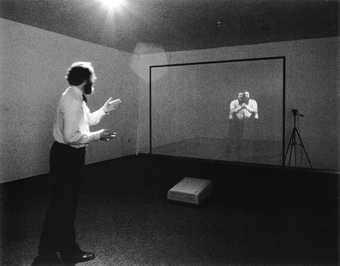

My earlier education was in psychology and my studies were in cognition. In these interactive pieces I was trying to open up areas of thought through the physical experience of interacting with the works. I made situations to call attention to our relationship to geometrical things, the space of a room and our position in that space. I wanted people to be aware of them moving through space (of a gallery) and the relationship of that space to the video space; the experience of both, and how they relate to each other.

David A. Ross

But what were you constructing – stages or sculptural spaces? It wasn’t a narrative, but were you creating situations in which choreographed narratives could occur, blank spaces for others to inhabit?

Peter Campus

I think the problem is that art making is not verbal. As a professor, I get paid to verbalise things that aren’t meant to be verbal. Often the descriptions are after the fact and always come up wanting for me. To describe works always feels like cheating, but for me Optical Sockets was a way to understand the original ideas behind geometry. The relationship of the mind-body to structures. Ideally, you would be aware of your presence in the space, defined by the cameras in the corners (the sockets) of an imaginary pyramid; the loci of the interaction determines the three-dimensional form, but only if you make a temporal summation of your actions and those of others in the space.

David A. Ross

What are you trying to do in your work? What do you think your job is, your responsibility as somebody putting artworks into the world?

Peter Campus

I have no idea. What aligns me with Douglas is this interest in the viewer of our work, although we do it in very different ways. In my interactive work the viewer has to be part of the piece to exist, but I think Douglas is a very generous artist to his audience.

Douglas Gordon

I think your work is incredibly wordless. When you talk about needing a person to activate it, I’m not sure what a man like me thinks about that, because when I saw your exhibition at the Albion Gallery, I enjoyed watching other people responding in a physical state, without words, without explanation, quite literally. I took a lot of pleasure watching people walk out of the camera shot. I identified with the game scenario, formally, literally and beyond.

Peter Campus

Okay, but 24 Hour Psycho is moving at such a slow rate frame by frame that it just throws everything back on the viewer, and if anything, if you’re not aware of yourself while watching 24 Hour Psycho, what are you doing?

Douglas Gordon

My big plan was that 24 Hour Psycho doesn’t really need to exist anymore. The idea of the future is not happening fast enough to be tangible and the past has slipped away too fast, so you don’t need to see an image at all.

David A. Ross

Do you know anyone who has watched it straight through?

Douglas Gordon

Yes, a few people. They are no longer with us…

David A. Ross

Peter, many people are familiar with your single-channel works – especially Three Transitions. Can you speak for a moment about how it evolved from your earlier single-channel works such as Double Vision?

Peter Campus

Three Transitions 1973

Film stills

Courtesy Kunsthalle Bremen

© Peter Campus

Peter Campus

Double Vision was about the evolution of vision, starting with the simplest eye, progressing through binary sight and ending with conceptual seeing. In Three Transitions I was stating something about the implied space in video, changes of time and space presented simultaneously. It looks magical, but it is simple and logical in the video medium.

Peter Campus

Double Vision 1971

Film still

Courtesy Kunsthalle Bremen

© Peter Campus

David A. Ross

It’s a work which follows your transitions in the cut, distorted image. It seems that you were interested in the mirror as a means of creating a different sense of space – of fracturing space – such as in the sequences in Third Tape 1976 of the portrait being constructed by reflections in fragments of a mirror placed at different angles. In that way I think you were involved with a vocabulary that was very much in the air, along with Robert Smithson and Dan Graham.

Peter Campus

Third Tape 1976

Film still

Courtesy Albion Gallery

© Peter Campus

Peter Campus

Correct. Mirrors were very important to me, as they were in works such as Kiva (a small mirror is hung as a mobile in front of the lens of a camera) and Interface, which I made in 1971 and 1972, and definitely under the influence of Bob Smithson.

David A. Ross

Are you interested in the specifically psychological dimension of your work?

Douglas Gordon

It is difficult to answer why you’re interested in something. I can only suppose that it’s the same for Peter as it is for me – that I stumble around in the morning and have a cup of coffee and a piece of toast, and then sometimes I think: wait a minute, that piece of toast… is looking right back at me. And you want to explore this little piece of phenomenology that you’ve experienced. You don’t go to university to study psychology or psychiatry and then make work about it. My fantasy is, Peter – say in relation to the sequence in Third Tape – that you were sitting there one morning over breakfast and started playing with these rectangular hand mirrors, and then suddenly you found yourself pursuing something with them which took you somewhere other than where you initially wanted to go.

Peter Campus

And after the fact we talk about Picasso breaking up space. The first impulses to make art are totally non-verbal for me. Only afterwards do I find a way to talk about it that refers to art history or some such thing. Thinking logically limits my thinking, so I allow rapid, illogical, non-verbal thought; in some ways it is more like the computer making rapid associations all over the place.

David A. Ross

When anyone watches a finished production or film, they obviously don’t see the effort that’s gone into it – or the grief and heartache, the financing problems…

Douglas Gordon

I went to art school for six long years and I studied film. The main thing that happened there was that I got to a point where I couldn’t enjoy film anymore. If I was watching a clip of Peeping Tom, for example, I would know exactly where the camera was, exactly what Powell and Pressburger had read, and I just couldn’t enjoy it.

David A. Ross

Maybe that was the necessary step for you to start filling the void with things that would entertain you?

Douglas Gordon

There is entertainment and there is enjoyment.

David A. Ross

Let’s just talk about pleasure…

Douglas Gordon

No. No pleasure. I’m from the west coast of Scotland… I suppose if you dig coal for five years, you might end up making a work about burning something. Whatever you study, what comes after is not a residue, but more a distillation of one’s interests. If we read Lacan and Derrida, then why wouldn’t we illustrate their texts? But I tried it once and didn’t like it.

Peter Campus

At art school we are constantly talking about Derrida and Lacan. But why do we do it? It’s just the wrong way to go at this. Art is a different way to explore philosophical issues. Philosophy can get bogged down in language; in art we use images and concepts to explore issues that are relevant to ourselves and our culture.

David A. Ross

Is it because to describe an experience that is so interior is so difficult to do?

Peter Campus

Yes, but before Derrida there was Picasso’s Cubism. There was the idea of deconstruction visually in the paintings of the Cubists long before it was presented to our culture on a verbal plate.

Douglas Gordon

I used to take my son to MoMA in New York every Sunday and walk around the modern collection. His favourite painting was Picasso’s Girl Before a Mirror. He would demand to go and see it every time and he would say: ‘Daddy, why is she looking at herself in a mirror for so long?’

David A. Ross

After 24 Hour Psycho you made a radical jump in Feature Film 1999. It seemed to be an attempt to move beneath the surface of action, to find a different kind of resonant visual code for the types of relationships Hitchcock (and others) explore in conventional cinema. Can you speak a bit about this?

Douglas Gordon

Feature Film 1999

Film still

Courtesy Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg

© Douglas Gordon

Douglas Gordon

Feature Film 1999

Film still

Courtesy Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg

© Douglas Gordon

Douglas Gordon

When Artangel asked me to do a project about fifteen years ago, I was listening a lot to film scores. With such a score you have an image that goes along with it. I thought if I dislocated the score, how much of the original image would still ‘see’? So I filmed James Conlon conducting Bernard Hermann’s score Hitchcock’s Vertigo with the Orchestra National de Paris. The only thing you is Conlon conducting, and his gestures are, for me, as important as Jimmy Stewart or Kim Novak in the film. It became a game for me to see how people might remember Vertigo. There were those who swore they had seen a frame of Novak in my film, so I told some people that I had inter-cut it with some frames, and others that I hadn’t. So we will keep that mythology alive.

David A. Ross

Does the idea of the hidden action behind underscore the whole structure?

Douglas Gordon

Well, yes, the two layers of hidden stuff – the first layer being that there really is an orchestra, so he looks like he’s acting, and then there is the film that you know, or at least your memory of it, that is ‘hidden’ beneath the orchestra.

David A. Ross

Both of you seem to be aiming to reach an essential space, the essential narrative. Do you believe that it is possible for a work of art to have a transcendent impact?

Peter Campus

One of my teachers once told me that your work should always transcend what you are doing, I like that, and I always tell my students that too. In other words, you set out to do something, but it is always something more.

Douglas Gordon

Or even just something else, not necessarily more. I’m really not going to make out that I’m from the gutter and had a terrible life, but I think the idea that art has to be more than something else is really disgusting to me; the idea of inspiration and gift and talent makes me puke. I despise the idea that art should elevate itself through the desire of the artist to elevate his or herself. With football it’s okay though…

Peter Campus

That’s a disagreement we have.

David A. Ross

But why elevate? The notion of to transcend doesn’t necessarily make a hierarchy. It really means going beyond in a way…

Douglas Gordon

Well, is it a sideways shift or an upwards shift?

David A. Ross

From the core to the outside.

Peter Campus

I just don’t know why it’s such a dirty word.

Douglas Gordon

You don’t know where I’m from… I’m from a Calvinist tradition and, believe me, I’m trying to shake it off…

David A. Ross

You think it’s okay for an artist to aspire to produce works that create the possibility of a transcendent moment?

Peter Campus

I would put it differently. I do think that was the huge limitation of postmodernism, and I see my young students moving away from that. I never bought into it anyway, so I don’t know why your generation did, Douglas.

Douglas Gordon

It’s not so much that you buy into something because you think it’s going to be good; it’s that you are coerced into it through the cultural environment of Baudrillard and others.

Peter Campus

But I always thought it was a reaction to people such as Rothko and all that…

Douglas Gordon

After about three years of not being able to engage with something because I couldn’t enjoy it, I went up to Glasgow to see the British Art Show in 1990, and I saw this beautiful piece by Bethan Huws, made from dried rushes tied into a knot, that stood up on its end and looked like little boats. That piece worked for me. It was like finding a wee key or something that I had lost.

Douglas Gordon

Feature Film 1999

Film still

Courtesy Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg

© Douglas Gordon

Peter Campus

Really enjoying an artist’s work is something we can agree on. I think it’s pointless being an artist if you don’t. However, I don’t totally believe you, because when I look at your work I see some variance between that and what you say.

Douglas Gordon

I only say that to make myself feel good, in public. When I go home I’m really into it… Inspire me please, God!

Peter Campus

Granted.

David A. Ross

Did you ever worry about what your job was as an artist?

Peter Campus

Not until maybe the past five or ten years, and it is also what my job is as a teacher. I am trying to see how we relate to our culture, how we artists contribute to our culture. I feel our function is very important – to expand understanding of self, community and our environment.

David A. Ross

But you know those are different?

Peter Campus

No, they’re not so different. I’m constantly questioning what our relationship is to society in general. I always pose that question in the first or second week of class, so, yeah, it is an issue for me. For example, we are submerged in this war, but what is our reaction to the war as artists. It is either to disengage from it and pretend there’s actually something else going on, or to try to relate to the violence. I think both those positions are part of our job as artists – to talk about all those things, and all the possible positions in-between.

David A. Ross

But a relationship to social violence, violence in any form, is just another colour in the palette, isn’t it?

Douglas Gordon

It is an important colour, maybe a primary colour at the moment. I remember when I was a student some of my teachers saying you have to question what your responsibilities are, and I thought, yeah, right, sure, no one else does it. But you see soldiers coming back from Afghanistan and the Gulf and they want to question it, but they don’t have a support system in place to help them through their questioning. It is perfectly valid if you’re an honest human being to give yourself an existential question before you go to bed at night. Peter – do you enjoy what you do?

Peter Campus

I do…

Douglas Gordon

Do you enjoy it when it is being seen?

Peter Campus

Not so much, I feel vulnerable then. I like looking at other artist’s work. I like best working on my art, being submerged in it, thinking about it. I remember that a piece ‘appeared’ to me when I was bored out of my mind on a train. I imagine that Psycho did not appear to you in any random way.

Douglas Gordon

Well, I have a story to tell. When I was a student at the Slade, I was bored, so I went up to Glasgow where my mum and dad live. The pubs were closed, all my pals were in bed, my family were asleep, but I wasn’t sleepy. I was in my brother’s room. Being a good Jehovah’s Witness boy I had never seen Psycho, because my mum had told me not to watch it. Said it was bad. But then I thought, damn it, Mum’s in bed so I can watch it, so I did. There’s a scene where Janet Leigh takes her bra off, and I thought: I’m going to watch that again, in slow motion. Then I thought, well, I’m going to watch the whole thing in slow motion, and it turns out that it was about 24 hours long.

David A. Ross

So out of repressed boredom came an idea to create a work that put people into a very different space.

Peter Campus

Boredom is a powerful tool.

David A. Ross

I think Warhol introduced boredom into art again in an interesting way, but video made it really possible.

Douglas Gordon

It’s a fairly crucial and horrific fact that people spend longer looking at a video monitor that isn’t working than a painting, waiting for something to happen, while there is a Barnett Newman just round the corner for them.

David A. Ross

Well, I think our training and our certain expectations of an aesthetic experience create the tension when you see videotape works in a gallery. Now it’s become rather common, but there was a time when it was a dissonant moment to see a TV in a public space. As John Baldessari said, video is just another pencil. I understand that both of you do drawings. Has drawing become important to you?

Peter Campus

As my education was in psychology, I never had an opportunity to draw in school. I have thought that what I make are diagrams. They are always after the fact, always after the ideas have gelled in my head.

Douglas Gordon

The only time I stopped drawing is when my teachers at art college told me not to stop drawing. So I stopped, and then I thought – what an idiot. I have thousands of drawings that are very ‘dark’. They’re not drawings of video installations, or anything like that.

Peter Campus

I’m so happy I never went to art school. I took some film classes, and that was helpful to see and hear in a different way, and then I ‘studied’ with three artists independently, Bob Grosvenor, Ian Wilson and Chuck Ross. I sat at their feet and listened to what they said, and what they said to me about my ideas.

David A. Ross

Douglas, you came out of a generation where art school was quite important, but you’ve never taught, or you don’t now?

Douglas Gordon

No. I kind of enjoyed teaching, but when I taught it was directly after I was a student, so it was just a continuation of art school actually. If you have been privileged enough to have been with a peer group of argumentative, nasty, loving bastards who are your friends at art school, it is very difficult to find that again. One of the ways is by being a teacher and you can force conflict between people, and I really prefer that in my private life.

Douglas Gordon

Feature Film 1999

Film still

Courtesy Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg

© Douglas Gordon

David A. Ross

Peter, you did collaborate a lot in your art when you worked with actors, but now you just see the world alone.

Peter Campus

I do think having two jobs, being an artist and a teacher, makes the collaboration not so important for me, because I’m constantly in dialogue, which I enjoy tremendously. I don’t need that in my art making to exist, but I wish that there was more opportunity for long unrecorded dialogue. It is one of the things that is missing in the art world.

Douglas Gordon

Come to my house for dinner.

Peter Campus

Okay, what night?

Douglas Gordon

I’m free every Tuesday. We have beef Wellington on Tuesdays.