Leonor Fini, Little Hermit Sphinx 1948. Tate. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2025.

Monsieur Vénus

10 rooms in Media Networks

This room brings together different approaches to the human form, exploring the body’s capacity to disrupt and question traditional hierarchies and gender categories

The emergence of new scientific, psychological and philosophical ideas in the early 20th century challenged traditional concepts of society and the self. Feminist writings focused on gender expression and women’s political and economic freedom. Ideas interrogating gender roles and the social order began to appear in the works of artists and writers. These radical changes brought the male-dominated world view into question. Distinctions between the binary categories of human and machine, mind and body, male and female became blurred. They made space for a more fluid understanding of the world and human relationships.

The artworks on display reflect this shifting worldview. They highlight connections between the visual and literary networks where these new ideas circulated. The room’s title Monsieur Vénus is taken from the 1884 novel of the same name by the French writer Marguerite Eymery (1860–1953), who published under the gender-neutral pseudonym Rachilde. Monsieur Vénus tells a subversive love story where traditional gender roles are reversed. Like many of the works on display, the novel is an exploration of sexuality and the fluidity of identity.

The works in this room reveal artists’ complex and often conflicting ideas. More traditional approaches to identity and the human form are in dialogue with works examining new subjectivities and the unconscious. Women and queer artists on display interrogate the male gaze and traditional gender categories. Together, these artworks reveal a remarkable range of networks, identities and stories from a transformative era.

Henri Matisse, Nude Study in Blue c.1899–1900

Traditionally, studies of the human form were central in art teaching studios and academies. Here Matisse adopts a new approach to the familiar subject and steps away from the then common sexualisation of the model’s naked form. However, he retains its objectification, utilising it for aesthetic purpose to explore the chromatic qualities of pure bold colour. Nude Study in Blue marked a crucial stage of Matisse’s artistic development. From this point onwards women and their form will populate the artist’s work almost exclusively.

Gallery label, September 2024

1/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

Natalia Goncharova, Linen 1913

This painting conveys the bustle of a commercial laundry. The two sides of the work are divided between traditionally male (shirts, collars and cuffs) and female (lace, blouses and aprons) items. This suggests an intimate relationship between two people. The text interspersed within the composition reflects Goncharova’s collaboration with transrational poets on the designs and illustration of artists books. These books brought together images and text with nonlinear styles that produced new, unexpected meanings.

Gallery label, September 2024

2/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

Edgar Degas, Little Dancer Aged Fourteen 1880–1, cast c.1922

The model for this sculpture is ballerina-intraining Marie van Goethem (1865–c.1900), then 14 years old. The artist first made a wax study while she posed, later adding real fabrics. When the wax sculpture was first exhibited in 1881, viewers were shocked by its realism. Van Goethem’s defiant pose and expression were described by critics as a ‘face marked by the hateful promise of every vice’. Young students at the Paris Opera from disadvantaged backgrounds were often exposed to sexual exploitation by wealthy patrons of the Parisian entertainment world.

Gallery label, September 2024

3/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

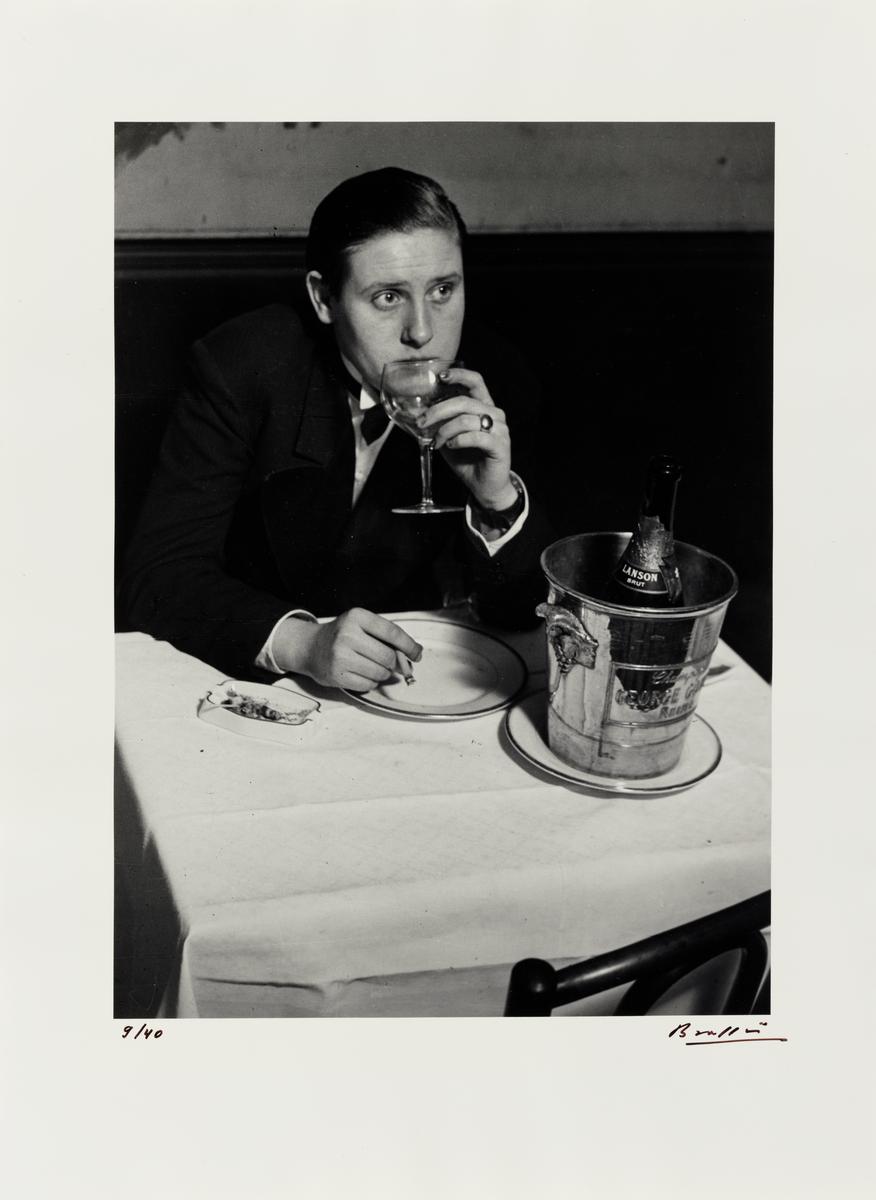

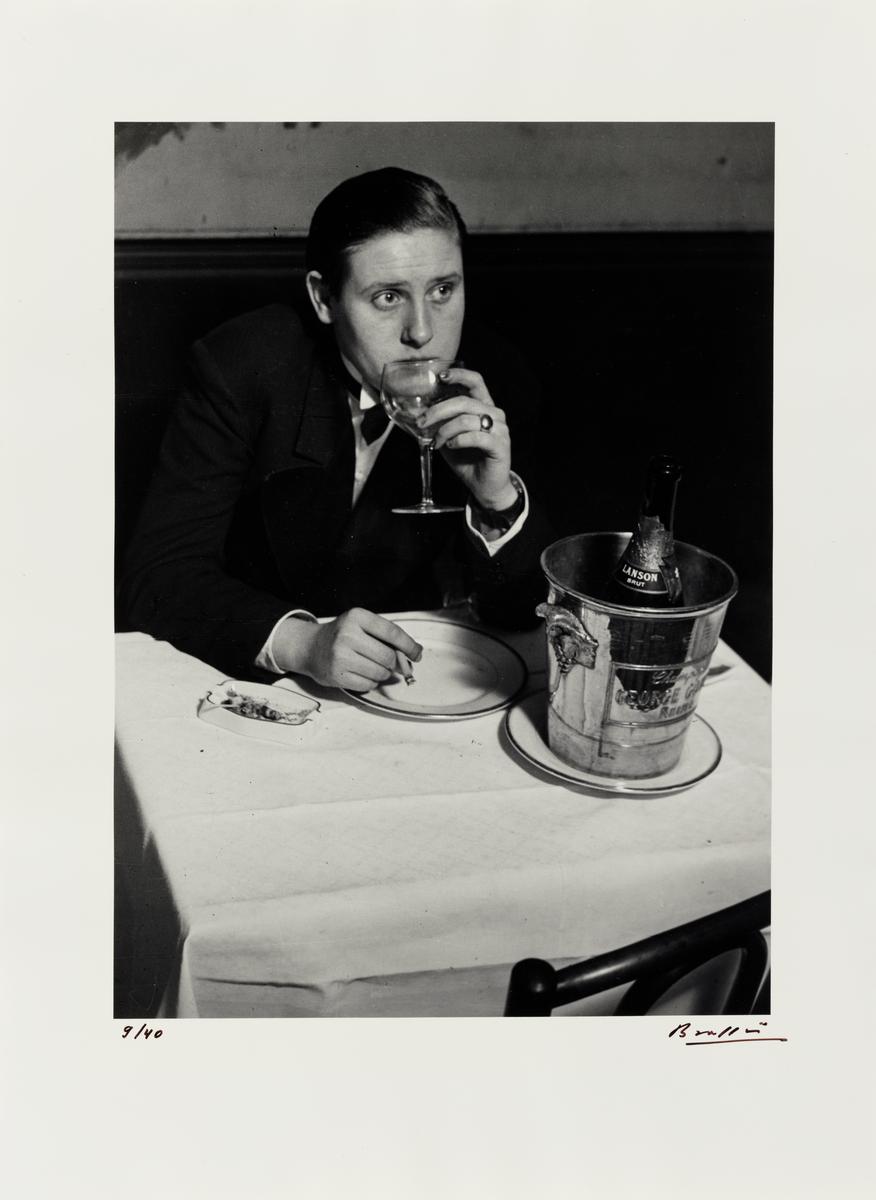

Brassaï, Young Lesbian at Monocle 1932, printed later

This is one of a series of photographs of Parisian nightlife taken by Brassaï throughout the 1930s. Its subject is Lulu de Montparnasse, owner of the renowned bar Le Monocle, one the first lesbian nightclubs in the city. Brassaï believed that ‘this underground world represented Paris … at its most alive, its most authentic’. His search for a new artistic vocabulary was influenced by modernist thinkers such as Marcel Proust (1871–1922). Proust’s novel In Search of Lost Time (1913–1927) unveiled a world full of queer undertones and references.

Gallery label, September 2024

4/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

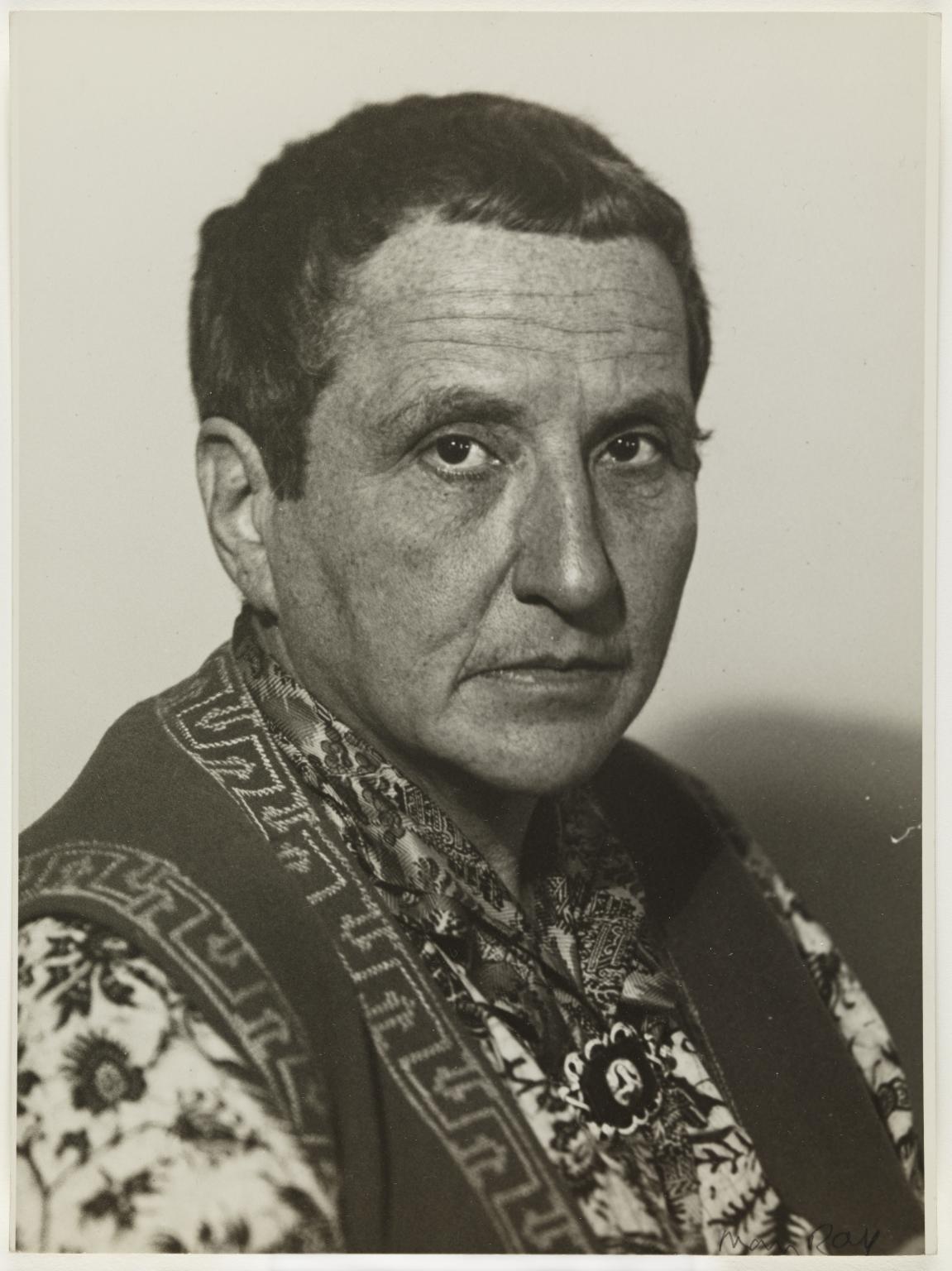

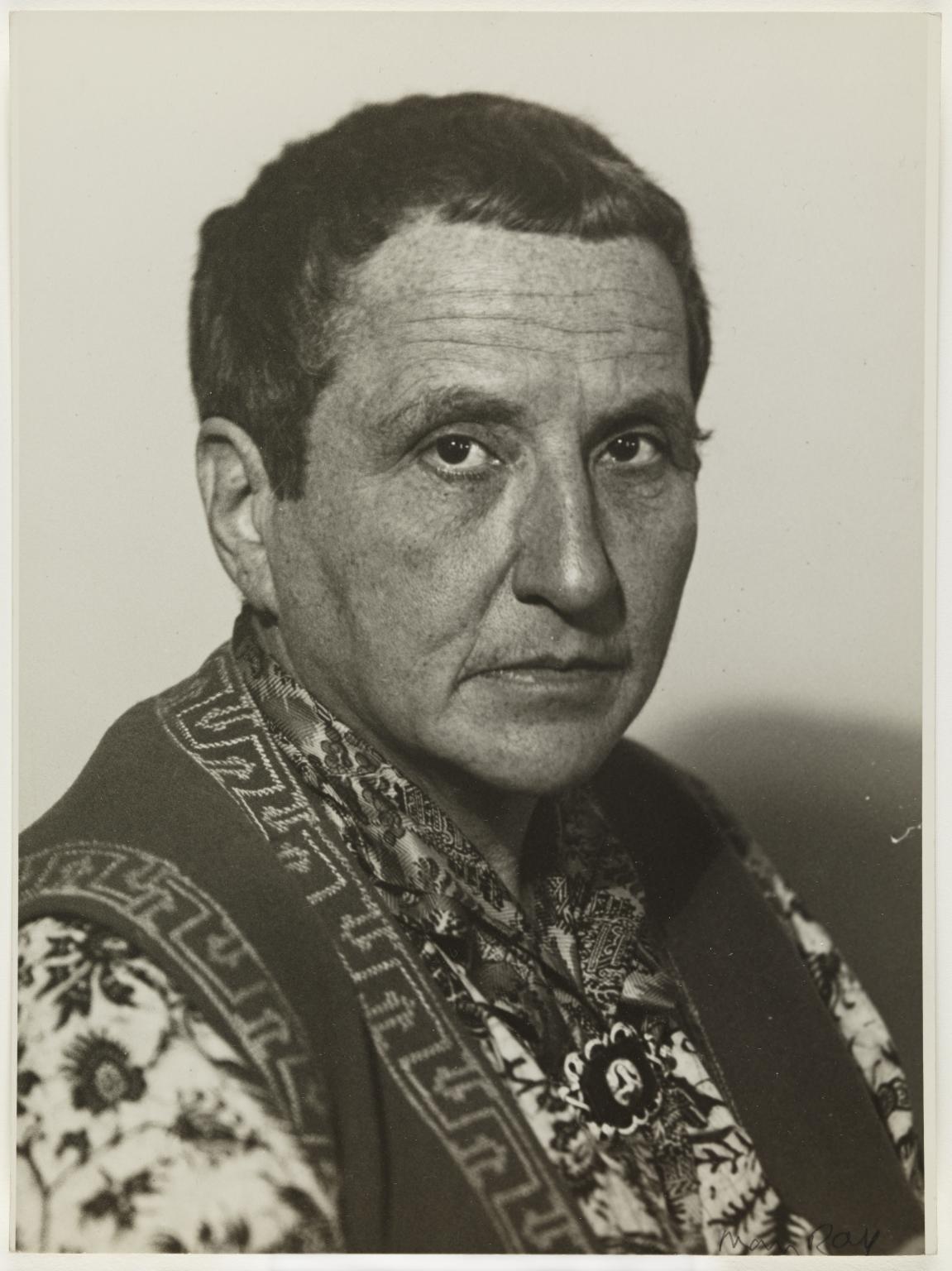

Man Ray, Gertrude Stein c.1920–9

This portrait of novelist and poet Gertrude Stein (1874–1946) is one of many photographs that Man Ray took of his friends, lovers, and contemporaries. The portrait of Stein highlights the poet’s queer identity and self-image that defied dominant gender stereotypes of the time. Man Ray moved to Paris in 1921 and was a prominent force in the development of the dada and surrealist art movements, which experimented with new techniques and visual languages to reflect the modern world.

Gallery label, September 2024

5/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

Pablo Picasso, Seated Woman in a Chemise 1923

Ballet dancer Olga Khokhlova (1891–1955), Picasso’s wife, was the model for this and several other works from the period. These depict idealised naked bodies, bathers and figures dressed in classical robes. Here Picasso paints Khokhlova in the so-called neoclassical manner – inspired by the visual culture of Greco-Roman antiquity. Khokhlova had introduced Picasso to the world of stage performance and theatre design. This, together with 16th and 17th-century drawings and murals, triggered Picasso’s interest in a more diverse stylistic practice. Khokhlova’s influence, however, is rarely acknowledged.

Gallery label, September 2024

6/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

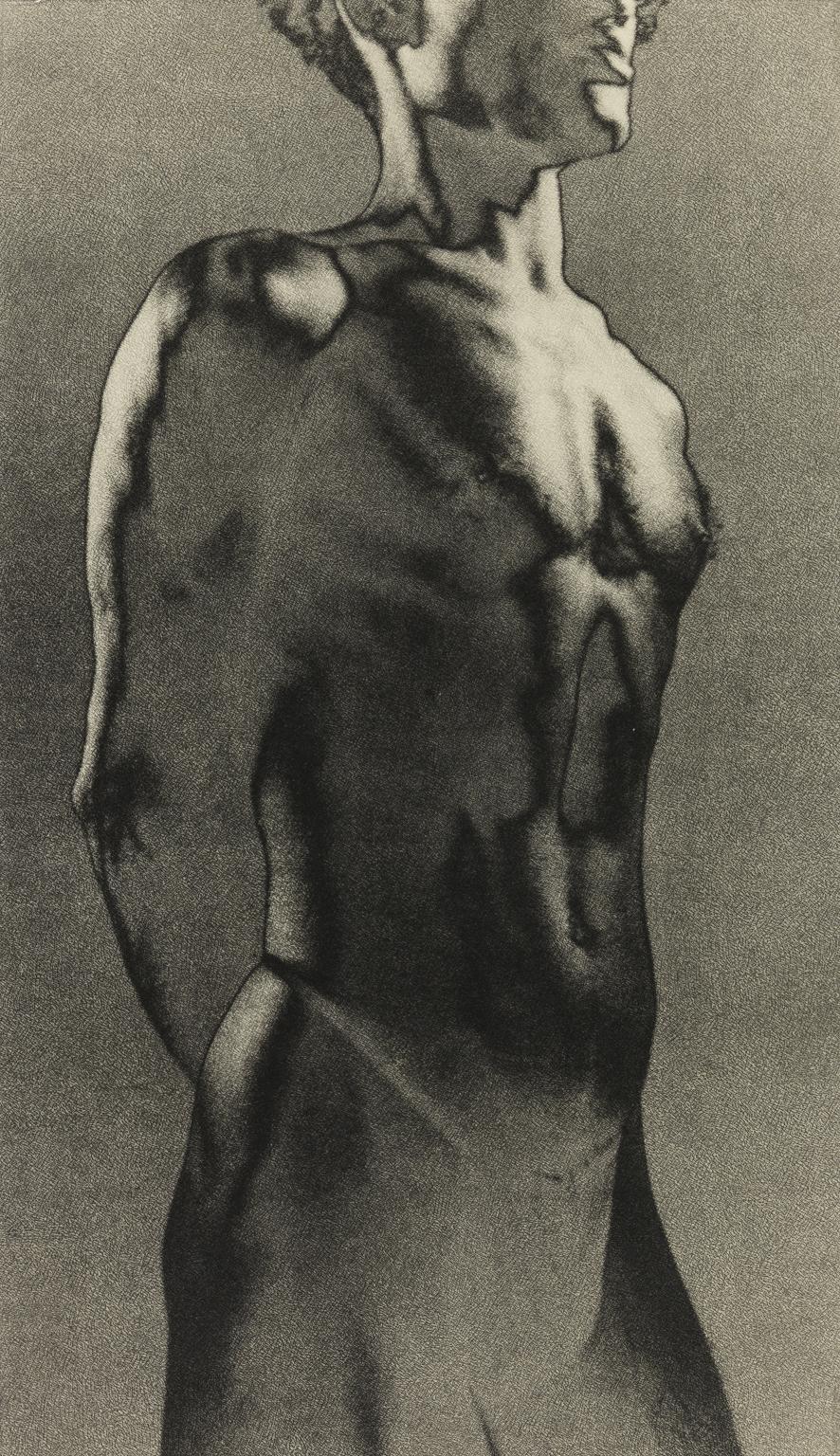

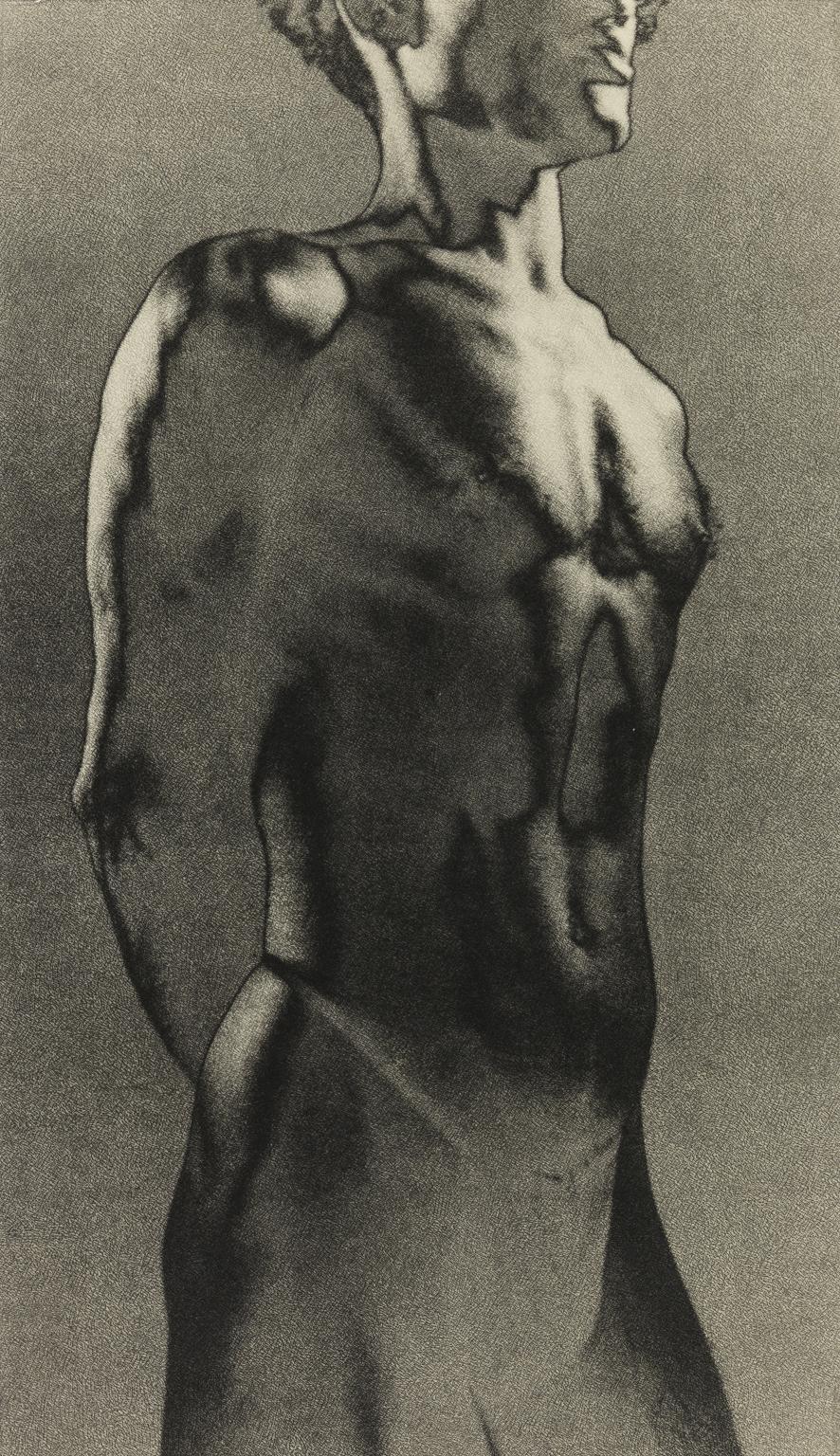

Lionel Wendt, Untitled after 1934

This print is a study of the male form, cut off at the head and thighs. Wendt’s studies were informed by his interest in Sri Lankan dance and music culture, as well as classical Greco-Roman statues. He experimented with techniques such as solarisation, where partially developed photographs are exposed to light, creating a bronze-like sheen. The fragmented appearance of some of these works magnified their seductive and erotic appeal. Through the tight framing of Untitled, Wendt transforms his model into a living sculptural fragment.

Gallery label, September 2024

7/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

Marie Laurencin, The Fan c.1919

Laurencin’s paintings often depict a world peopled exclusively by women. Shown in pairs or groups, they offer a vision of female intimacy and autonomy. The pairing of framed images shown in The Fan is ambiguous. It has been suggested that the woman in the oval frame is the artist herself. The identity of the other woman, however, is uncertain: is she a picture, or a reflection in a mirror? Laurencin created a series of 10 etchings of women with fans to illustrate a collection of poems dedicated to her and written by her friends. It was published in 1922 as a limited edition titled L’Eventail (The Fan).

Gallery label, September 2024

8/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

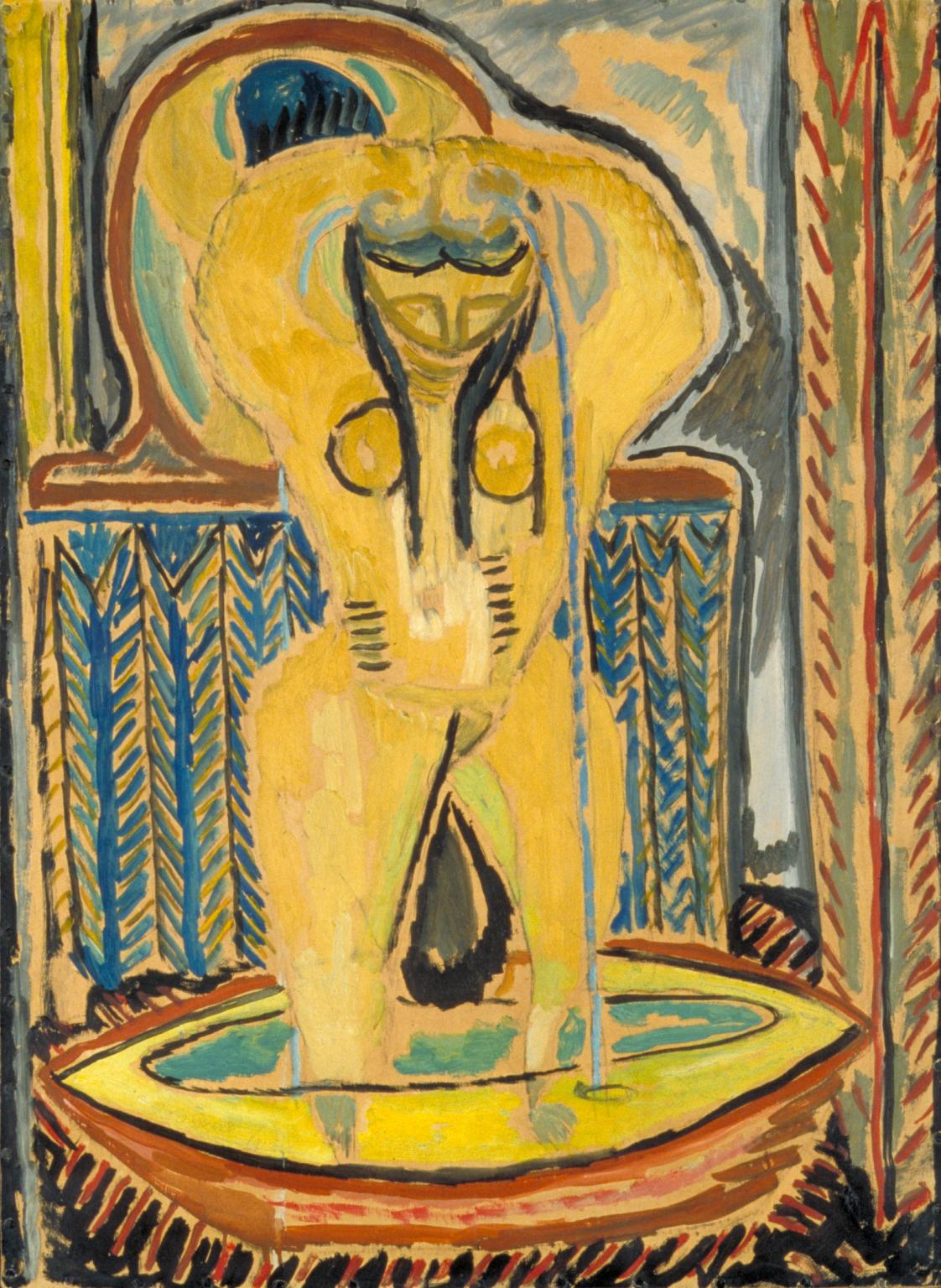

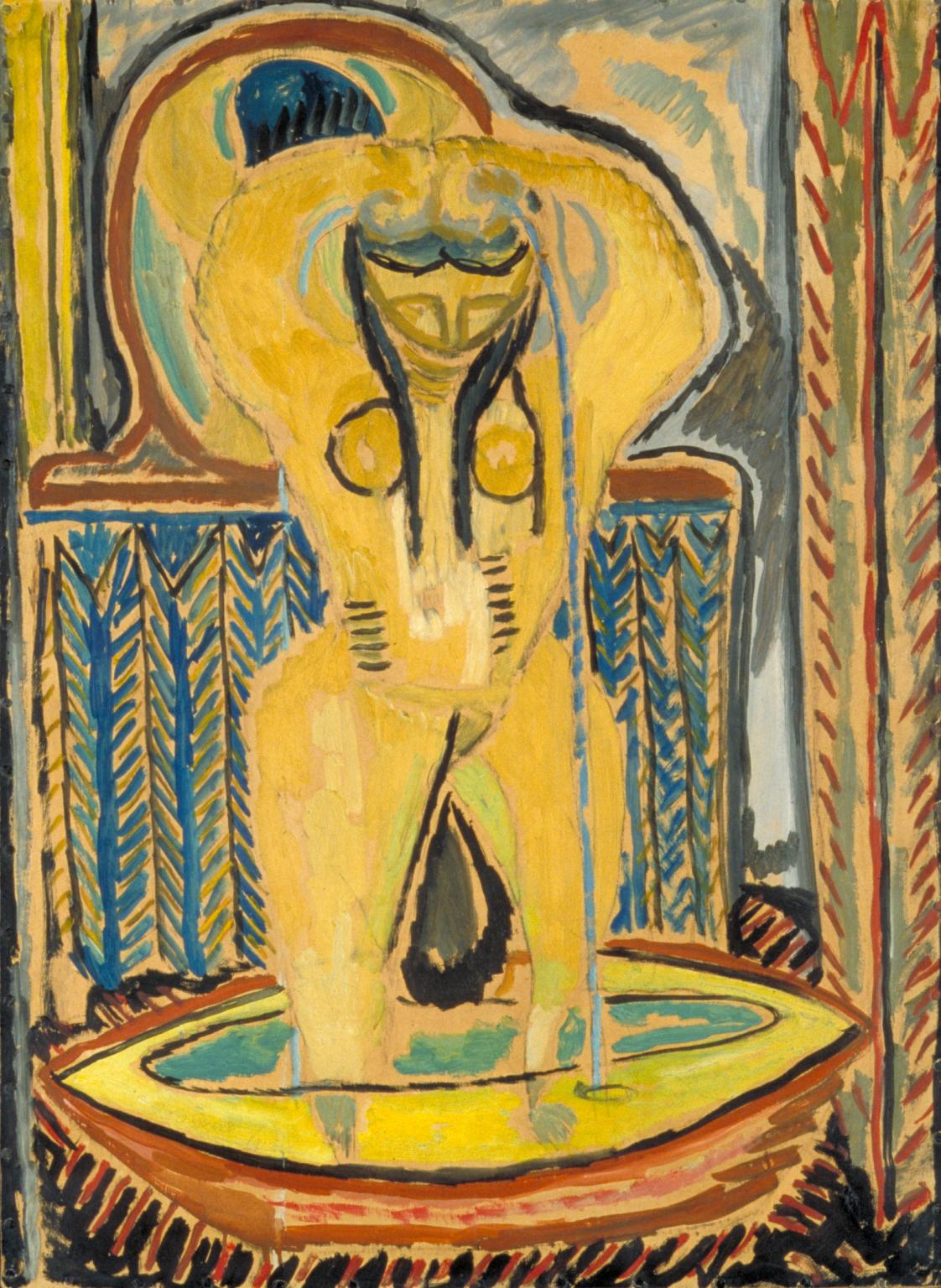

Duncan Grant, The Tub c.1913

The Tub shows a figure with flattened breasts, an accentuated abdomen and broad shoulders. A mirror is placed in the background of the painting, but it is partially covered by the figure itself, hiding its reflection from the viewer. These elements suggest a portrayal of the naked body that is not sensualised. Grant was a member of the Bloomsbury Group, a closeknit London community of artists, writers and intellectuals who embraced a culture of sexual equality and freedom. As is the case here, their works were often influenced by the aesthetics of sculptures arriving in Europe in the aftermath of colonial conquest.

Gallery label, September 2024

9/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Bathers at Moritzburg 1909–26

This painting shows Kirchner’s artist friends and their models bathing in a secluded woodland spot at the Moritzburg ponds outside Dresden, Germany. Kirchner and his friends were members of the Brücke group. Inspired by thinkers such as philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), Brücke artists promoted cultural renewal, a communal lifestyle and a cult of nature by rejecting tradition. Such notions also fuelled the right-wing ideology that culminated in the rise of National Socialism in the 1930s, when ideas around health and the body were used as a tool for the perpetuation of racial purity.

Gallery label, September 2024

10/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

Leonor Fini, Little Hermit Sphinx 1948

Fini’s paintings depict women as complex and powerful beings. Little Hermit Sphinx shows a surreal and unsettling scene. A sphinx sits at the threshold of a decrepit building with a human organ hanging above its head. The sphinx is a mythological creature that is part lion and part woman, with the wings of a bird. In 1947 Fini underwent a hysterectomy. The bleeding flesh above and the broken egg below the sphinx might point to the artist coming to terms with infertility. Here the Sphinx assumes a genderless state, becoming Fini’s alter ego and a recurrent symbol of feminine empowerment in her work.

Gallery label, September 2024

11/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

Sylvia Sleigh, The Bride (Lawrence Alloway) 1949

Here Sleigh paints her partner, art critic Lawrence Alloway (1926–1990), dressed as ‘Hetty Remington’. Hetty was Alloway’s alter ego, who Sleigh described as ‘a mythological character in our love game’. For the portrait, Sleigh picks a private and enclosed setting and pale pastel colours. Alloway’s clothing references the styles worn by powerful women in court in Tudor England. The work offers a touching glimpse into the couple’s intimate life. Too transgressive to exhibit until decades afterwards, this portrait documents the fluid gender play explored by Sleigh and her partner.

Gallery label, September 2024

12/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

Louise Bourgeois, Fillette (Sweeter Version) 1968–99

This sculpture depicts an enlarged phallus, made by layering latex over plaster to create a fleshy, tactile texture. The French word ‘fillette’ translates to ‘little girl’. The phallus is a symbol often associated with power and masculinity. Bourgeois’ choice of title creates gender ambiguity and is in playful contrast with the shape of the sculpture that ridicules the patriarchy. Bourgeois made this work in the late 1960s in the wake of second-wave feminism, a social movement that promoted debates around gender and reproductive rights, sexuality and domesticity, amongst others.

Gallery label, September 2024

13/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

Franciszka Themerson, Stefan Themerson, Frame from The Eye and the Ear 1945, printed c.1950s–1970s

This photograph is a film still taken from the experimental collaborative film The Eye and the Ear (1944–5). The film attempts to translate sounds into visual equivalents. It uses photographic techniques to depict fragmented body parts and abstract, biomorphic forms. The film was made in England, where the artists had established a vibrant creative community. They founded a publishing house, Gaberbocchus Press, which produced over 60 titles.

Gallery label, September 2024

14/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

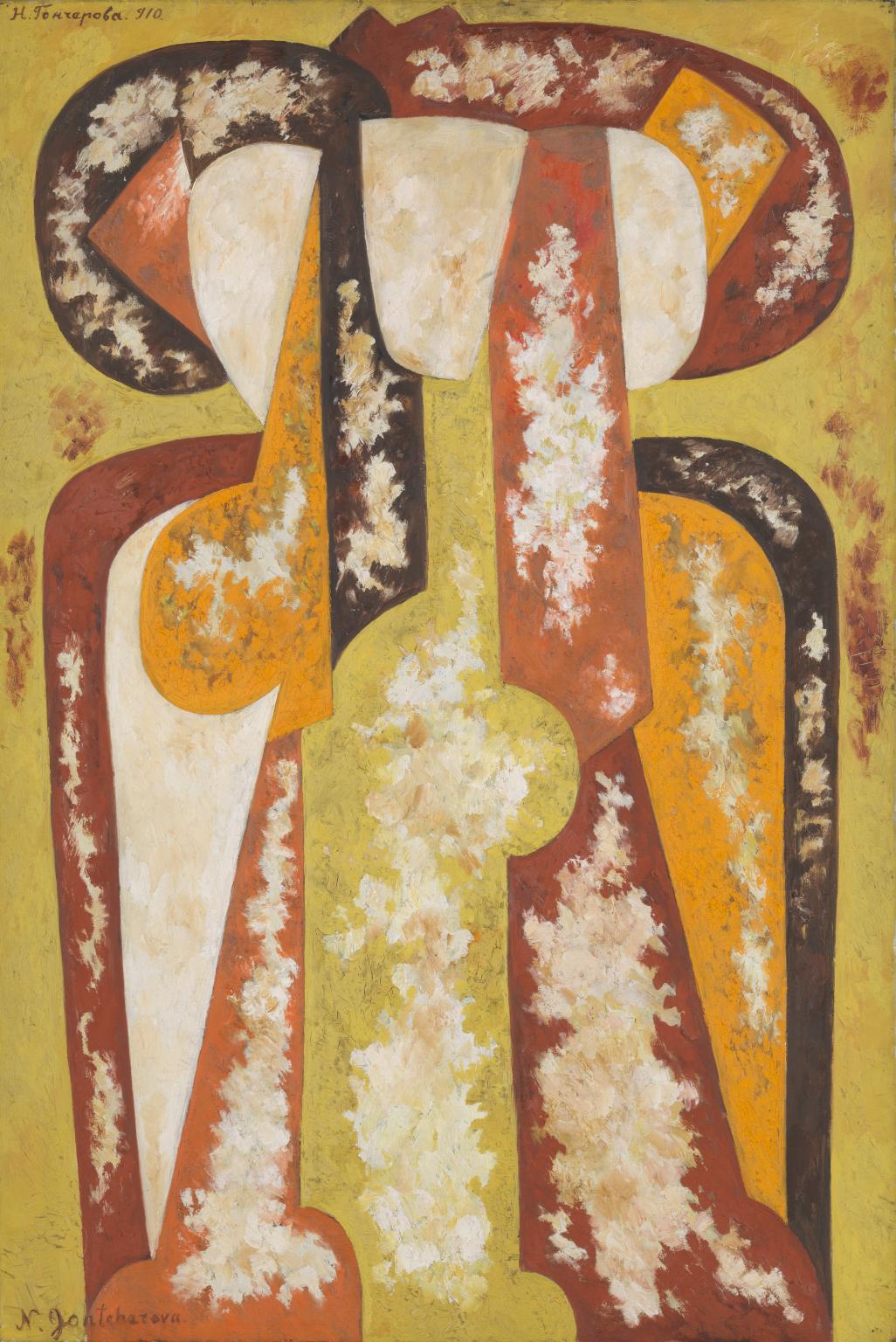

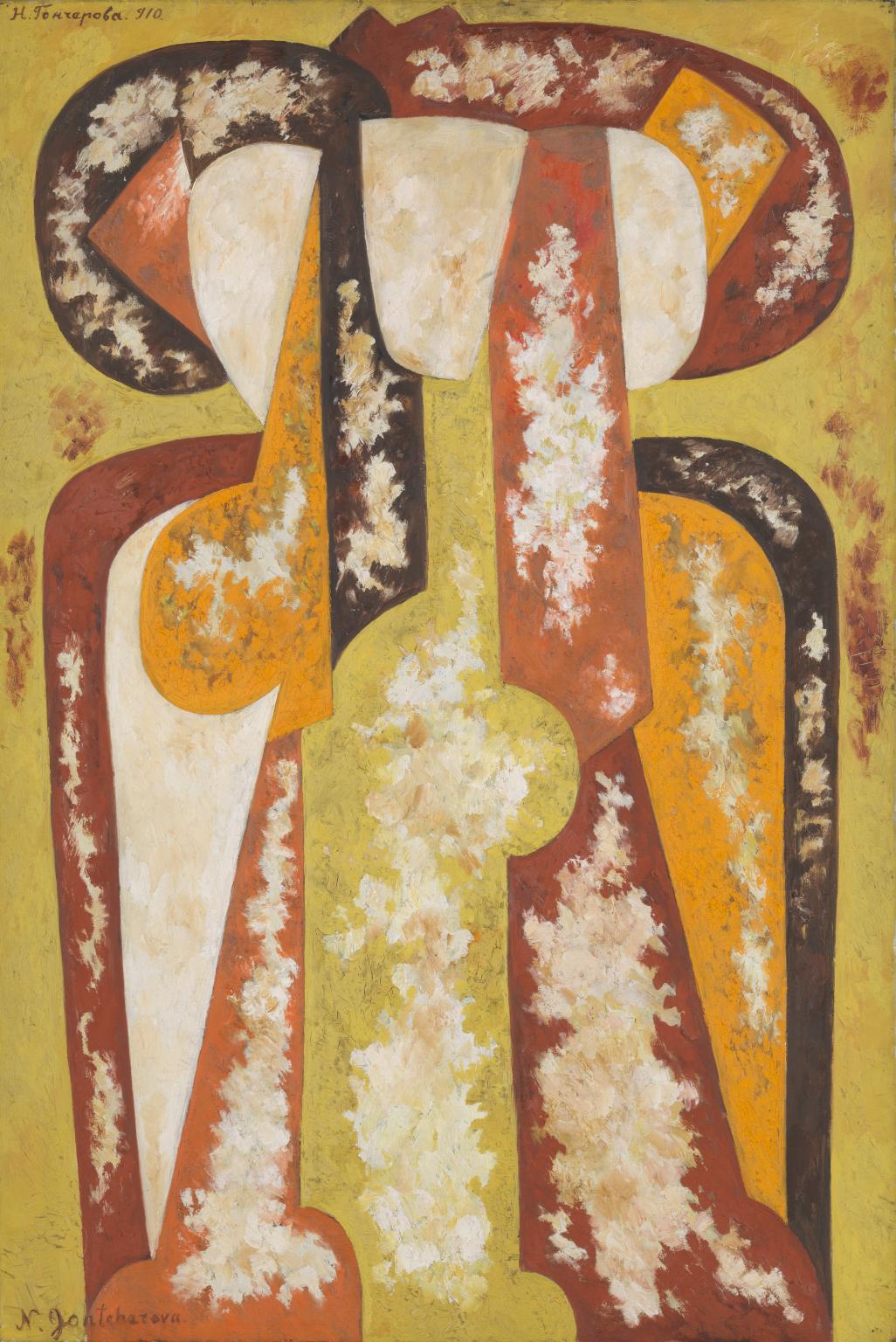

Natalia Goncharova, Three Young Women 1920

The rhythmic forms and restricted colour palette of white and ochre indicate Goncharova’s experience with stencil making. The naked bodies in the painting are not sexualised. This is in contrast with many compositions of Goncharova’s contemporaries, which often objectified women’s bodies. In the 1920s Goncharova established her first professional studio in Paris. She developed a successful practice that encompassed teaching, painting, book illustration, fashion, costume and theatre as well as interior design.

Gallery label, September 2024

15/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

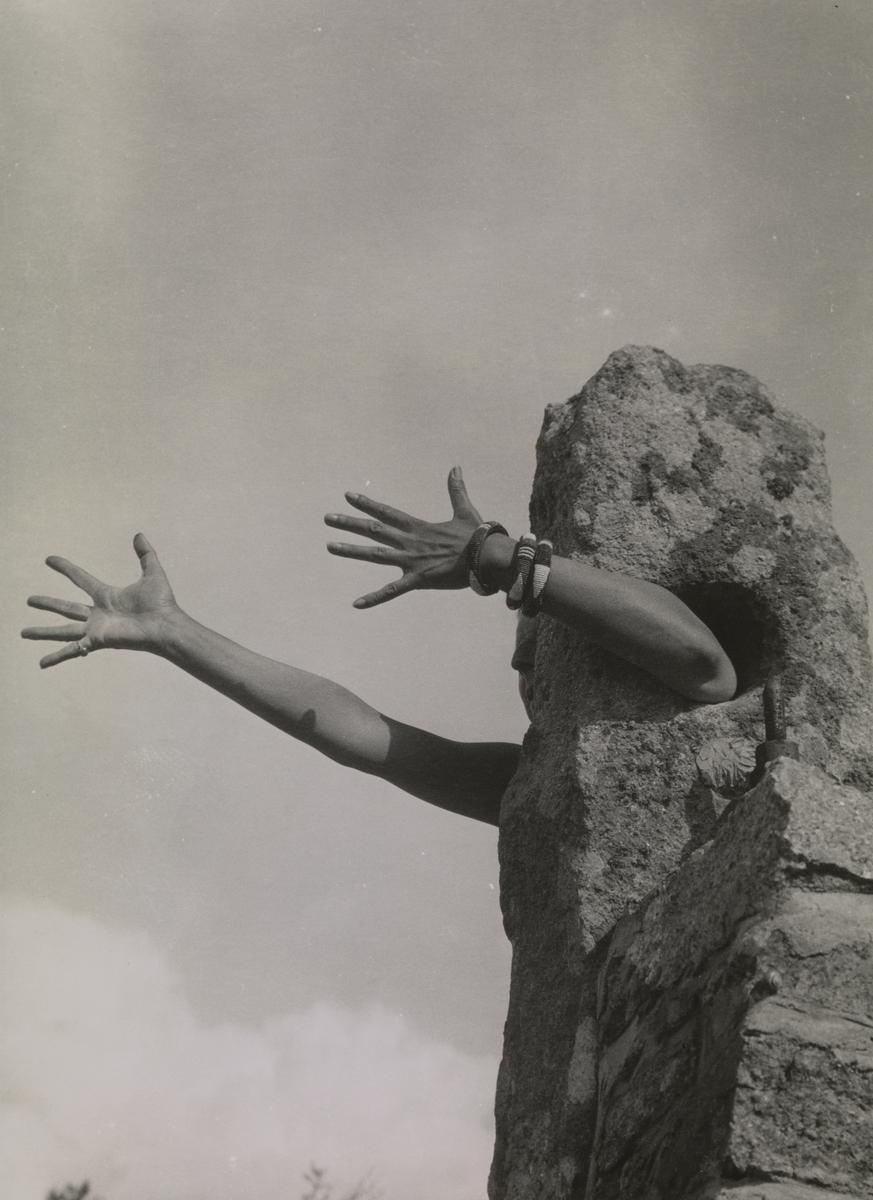

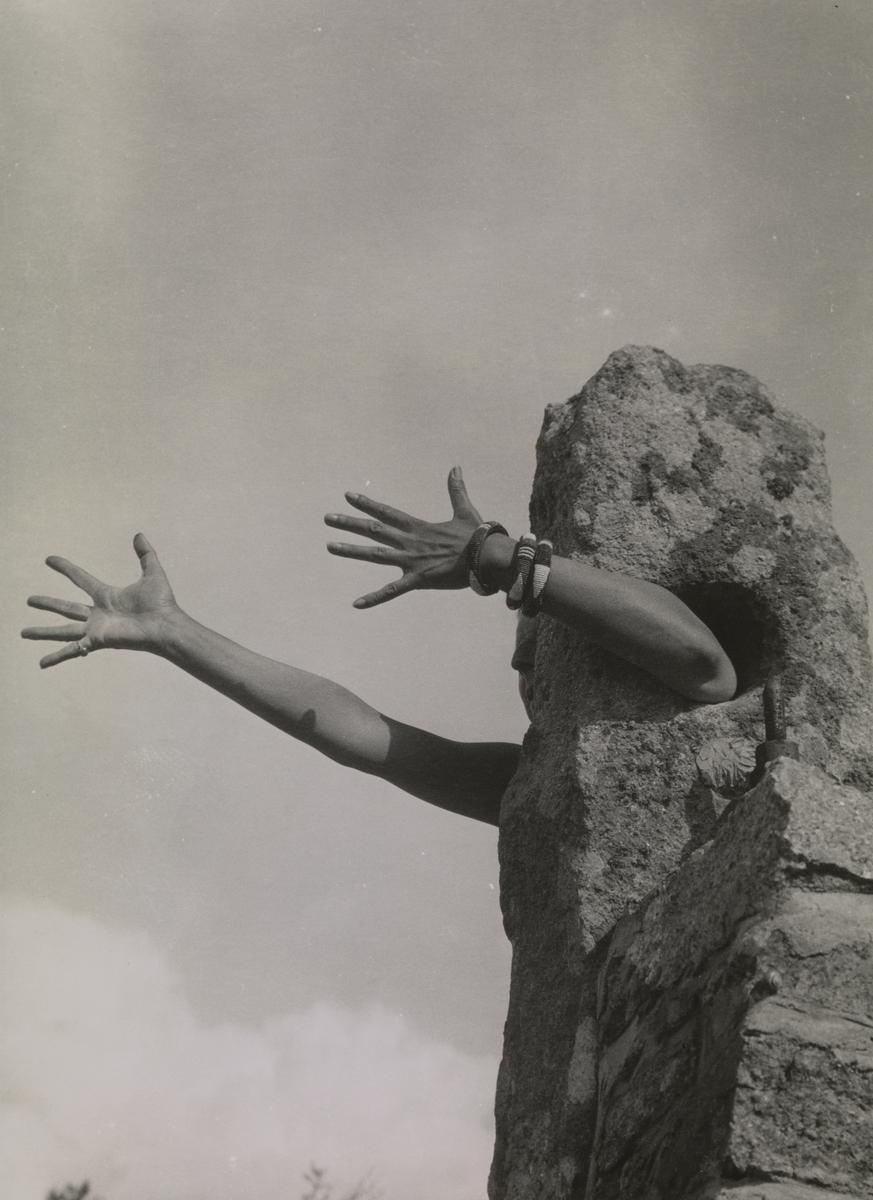

Claude Cahun, I Extend My Arms 1931 or 1932

As photography became more widely accessible, it introduced new ways for artists to explore and project their own self-image. Cahun explored gender fluidity as a photographer, writer and thinker. This self-portrait shows Cahun ‘wearing’ a monolithic rock as a mask or costume. While the rock has a distinct phallic form, the artist’s arms extending from it defy a gendered reading of the image. In the autobiography Disavowals (1930) the artist stated: ‘Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me’.

Gallery label, September 2024

16/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

Kati Horna, Ascent to the Cathedral, Spanish Civil War, Barcelona, Spain 1937 1937

Horna travelled to Spain in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War to document the conflict at the request of the Spanish Republican government. This print’s composition reflects Horna’s work as a layout and photomontage artist for anarchist publications. By blending two images – a portrait of a woman and a brick building with two barred windows – the artist creates a surreal and unsettling scene. Horna’s practice was informed by the surrealist experimentations of the Bauhaus, a German modernist art movement.

Gallery label, September 2024

17/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

Salvador Dalí, Metamorphosis of Narcissus 1937

This artwork is inspired by a poem by Roman poet Ovid where young Narcissus fell in love with his own reflection in a pool. Having realised that his love could never be reciprocated, Narcissus pined away, turning into a flower. Dalí wrote a homonymous poem to be exhibited alongside the work. This literary component adds additional layers of meaning to the painting. Recent scholarship suggests that it evokes the emotional turmoil that followed the murder of the poet Federico García Lorca (1898– 1936) – with whom Dalí had an intimate relationship – and the strengthening of the artist’s bond with his wife, Gala.

Gallery label, September 2024

18/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

Max Ernst, Pietà or Revolution by Night 1923

Ernst was a surrealist artist. Inspired by the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud’s (1856–1939) theory of the unconscious, surrealism used irrational images to portray the working of the human mind. Here Ernst replaces the popular Renaissance scene of Madonna cradling the body of Christ (known as Pietà) with an image of the artist himself, held by his father. Ernst paints his father following the traditional iconography of the Madonna, Mother of Christ. He subverts the original scene, showing instead a father figure in a caring role traditionally associated with women and mothers.

Gallery label, September 2024

19/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

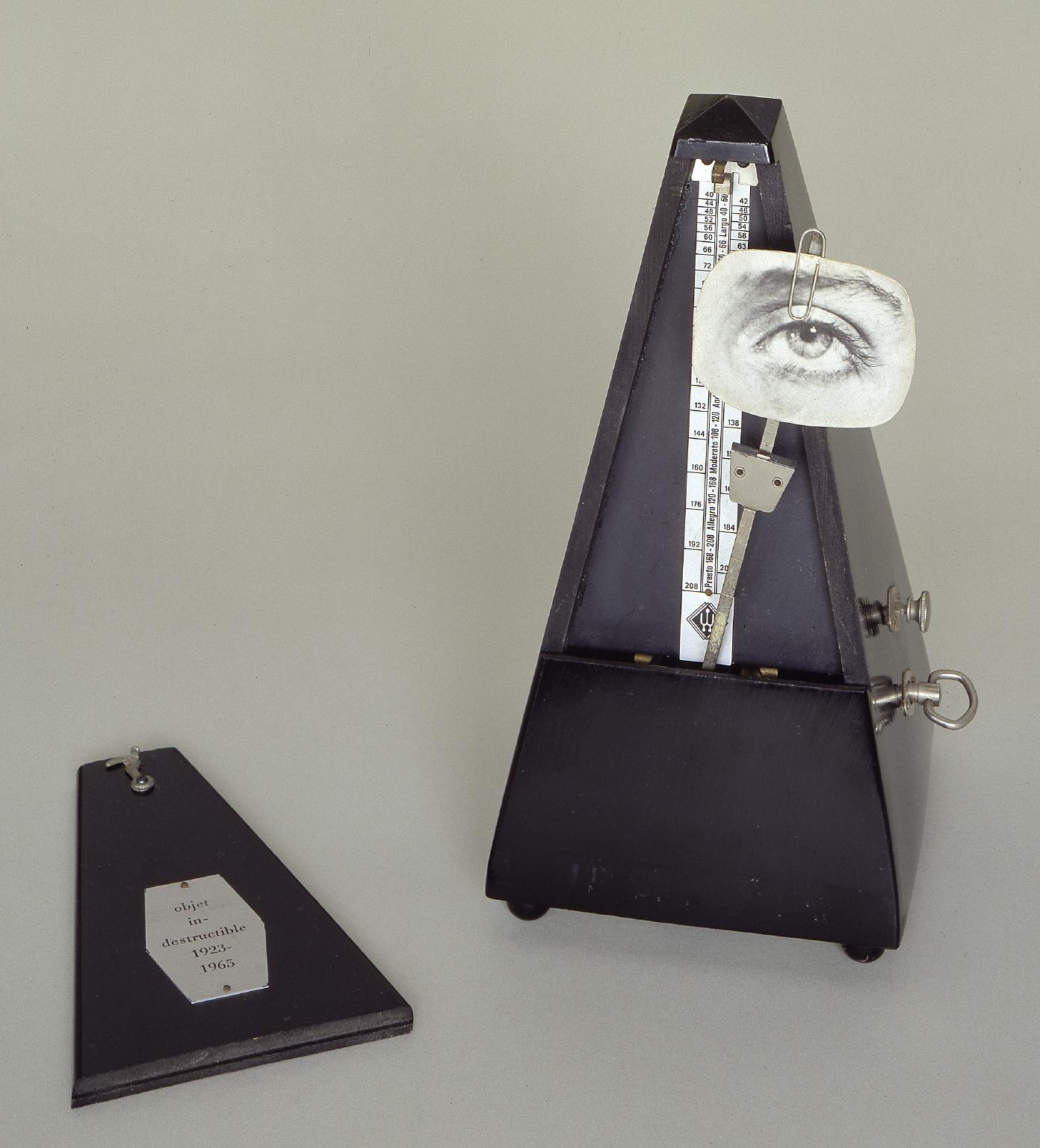

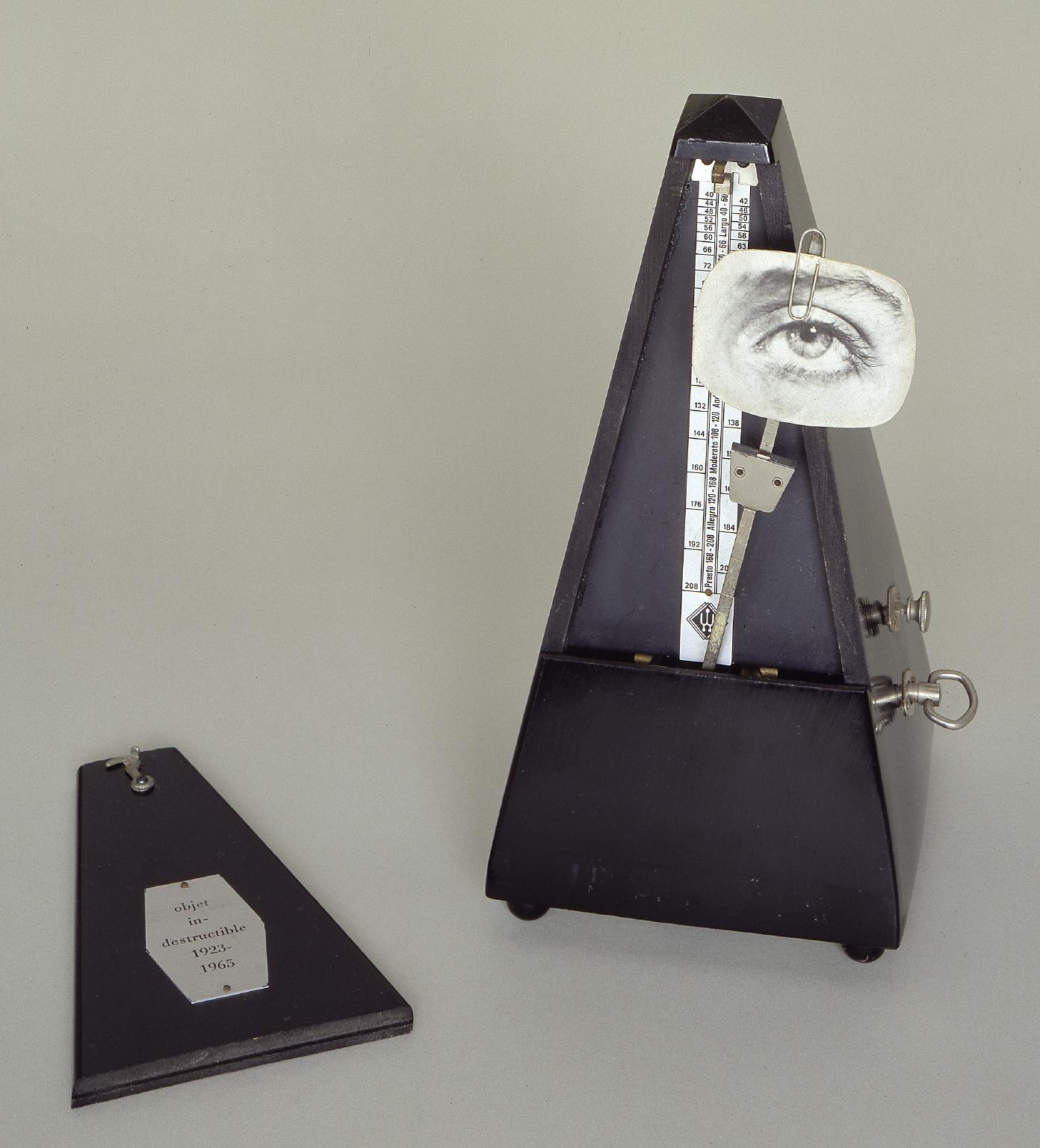

Man Ray, Indestructible Object 1923, remade 1933, editioned replica 1965

Man Ray made the first version of this object shortly after his partner, the photographer and model Lee Miller (1907–1977), left him. Attaching a photograph of Miller’s eye to the metronome, he linked his memory of her to the idea of an insistent beat or pulse that was both irksome and unending. The presence of Miller’s eye also raises interesting questions regarding the gaze. Man Ray recalled: ‘A painter needs an audience, so I also clipped the photo of an eye to the metronome’s swinging arm to create an illusion of being watched as I painted’.

Gallery label, September 2024

20/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

Dorothea Tanning, Nue couchée 1969–70

This is one of Tanning’s soft sculptures that evoke bodily forms. The artist described them as ‘living materials becoming living sculptures, their life span something like ours’. The sculptures are made out of a combination of textiles stuffed with wool and various objects. Here Tanning uses table tennis balls to create the suggestion of vertebrae protruding from the fabric. Nue couchée straddles the divide between object and being, animate and inanimate. Tanning resisted interpretations of her work focused on gender and sexuality. Instead, these soft sculptures are expressions of the artist’s imaginative fantasy world.

Gallery label, September 2024

21/21

artworks in Monsieur Vénus

Art in this room

Sorry, no image available

You've viewed 6/21 artworks

You've viewed 21/21 artworks