The Shape of Words

9 rooms in In the Studio

See how artists explored the abstract and expressive potential of words, letters, signs and calligraphy

This display offers an account of artistic experiments involving text and abstraction, shared by artists whose paths intersected across North Africa, Asia, Europe and Latin America. Their explorations occurred at critical political, social and art historical moments of transformation during the mid-twentieth century. The processes set in motion globally during this period, such as decolonisation, led to a rise in transnational political alliances and cultural solidarities. This era was filled with a sense of rebellion and innovation in the arts.

The connections and exchanges formed by artists as they moved across the globe resulted in a variety of visual expressions, often shaped by their unique trajectories or memories of their distant homes. While some artists pursued these approaches independently, others were part of schools and groups. These included: the Casablanca Art School, CoBrA (acronym for Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam), the Khartoum School, Bauhaus, as well as artistic currents such as Lettrism, Surrealism and Saqqakhana.

Following the devastation of the two world wars, artists across different cities were already experimenting with modes of abstraction, and the figure had all but disappeared from painting. Artists from newly independent countries sought new artistic vocabularies rooted in their local visual heritages. Working within a continuum of forms across history, many experimented with letters and script as the basis for new, anticolonial, abstract languages. These forms often converged to suggest figures, landscapes and cityscapes at the intersection of abstraction and representation.

At the same time, European artists turned to Asia and North Africa for new artistic ideas. These ranged from the interlocking geometric shapes in Kufic script to the fluid brush marks in Japanese and Chinese calligraphy. This display demonstrates some of these transformative encounters, that pushed artists to reconceive ideas of depth, surface and materiality.

Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor

Syed Sadequain Ahmed Naqvi, Four Figures Sitting in Paris 1967

Sadequain, a poet and a painter, was born into a family of calligraphers, a tradition he drew on throughout his career. Between 1960–67, he lived in Paris, socialising with Négritude thinkers (an anticolonial movement centred on Black identity) and exhibiting in spaces where Lettrist artists had shown, like Ibrahim El Salahi. This painting links Sadequain’s text-based abstract expression to 20th-century transnational political movements, with sweeping lines and semi-abstract figures foreshadowing the calligraphic works and murals he created in Pakistan after 1967.

Gallery label, March 2025

1/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

Mirtha Dermisache, Untitled c.1970

Dermisache utilises asemic writing –abstract or invented scripts that resemble letters but are in fact unreadable. Her method involves using black ink on paper to create the impression of personal letters or handwritten books. Situated at the intersection of politics and poetics, her use of illegible text symbolise resistance to state censorship during Argentina’s dictatorship. Through her work, Dermisache addresses themes of communication, incoherence, and cacophony found in Argentine literary culture.

Gallery label, March 2025

2/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

Mirtha Dermisache, Untitled c.1970

Dermisache utilises asemic writing –abstract or invented scripts that resemble letters but are in fact unreadable. Her method involves using black ink on paper to create the impression of personal letters or handwritten books. Situated at the intersection of politics and poetics, her use of illegible text symbolise resistance to state censorship during Argentina’s dictatorship. Through her work, Dermisache addresses themes of communication, incoherence, and cacophony found in Argentine literary culture.

Gallery label, March 2025

3/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

Mirtha Dermisache, Untitled c.1970

El-Salahi combines African and Arab cultural motifs with elements of Arabic calligraphy. Here, strange animal and plant-like forms, faces, and skeletons emerge from the broken calligraphic lines and morph into mask-like, totemic figures. In the wake of Sudan’s independence from colonialism, El-Salahi looked to his local environment for inspiration. He developed a distinctive visual language later identified as the ‘Khartoum School’. He stated, ‘I wrote letters and words that did not mean a thing. Then ... I had to break down the bone of the letter’.

Gallery label, March 2025

4/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

Mirtha Dermisache, Untitled c.1970

Dermisache utilises asemic writing –abstract or invented scripts that resemble letters but are in fact unreadable. Her method involves using black ink on paper to create the impression of personal letters or handwritten books. Situated at the intersection of politics and poetics, her use of illegible text symbolise resistance to state censorship during Argentina’s dictatorship. Through her work, Dermisache addresses themes of communication, incoherence, and cacophony found in Argentine literary culture.

Gallery label, March 2025

5/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

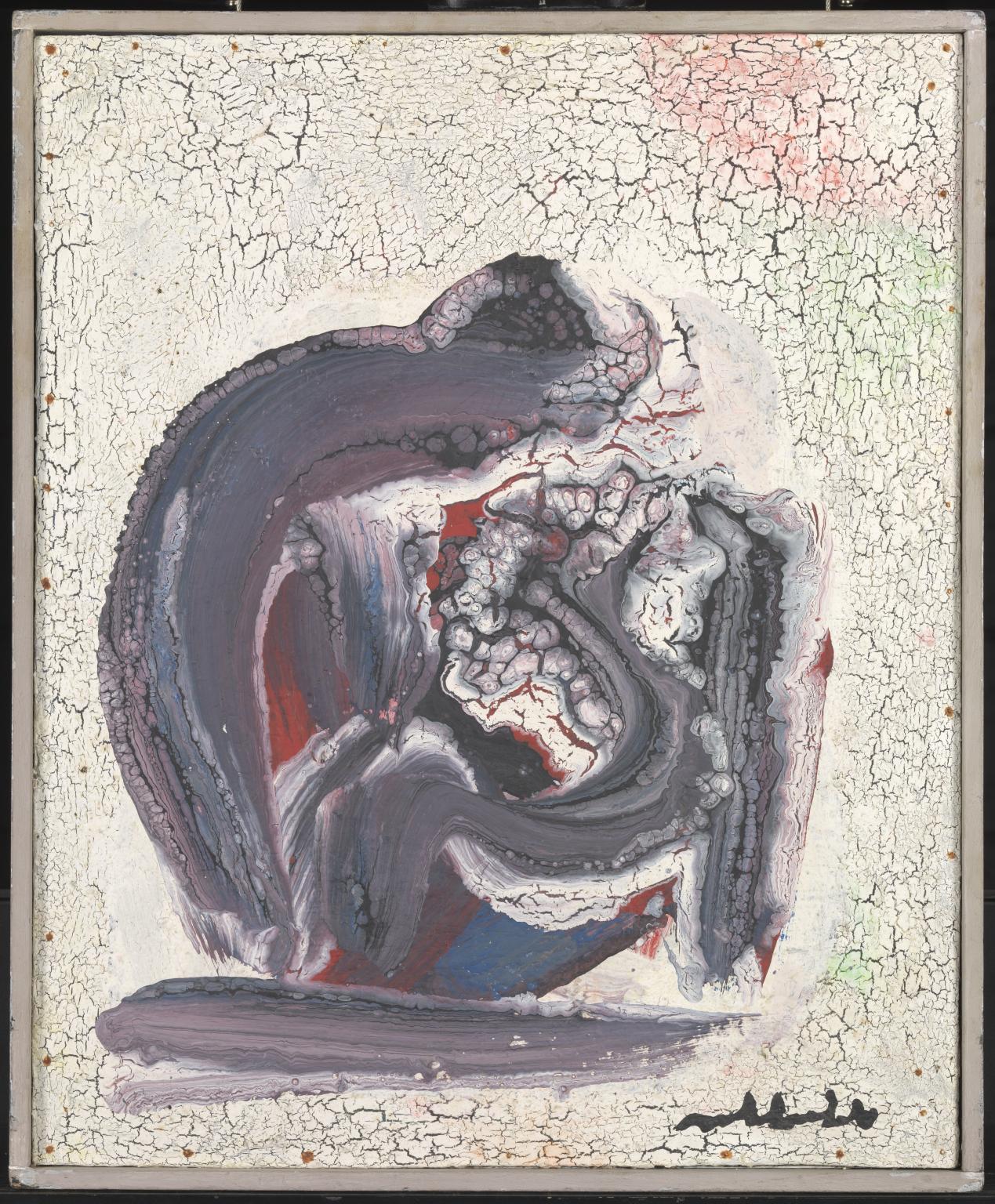

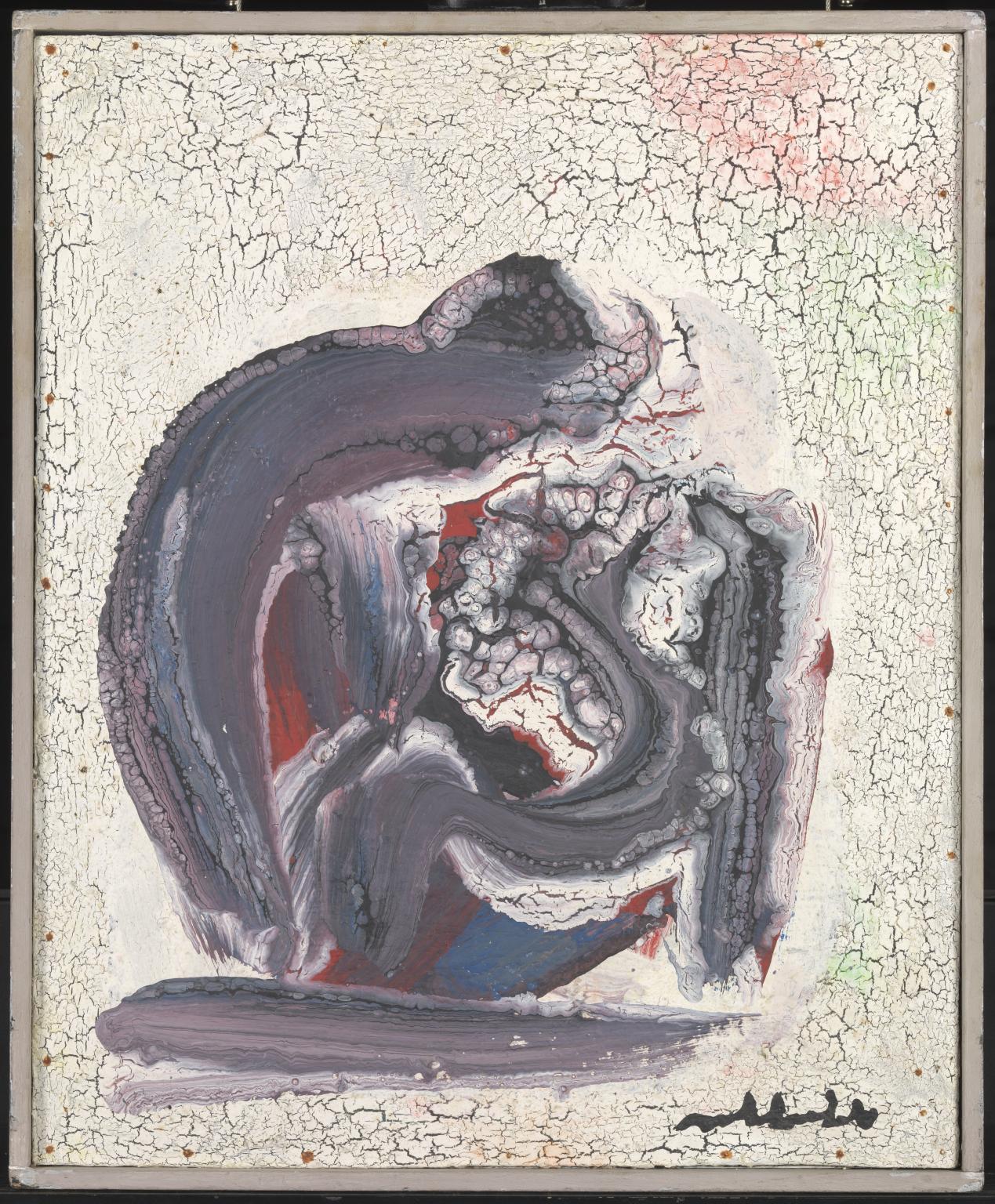

Hamed Abdalla, Lost or Escaped 1966

Abdalla trained in calligraphy and engaged with the principles of Islamic geometry. In this painting, the rounded, interlacing forms allude to bodily shapes or fragments. Together, they make up the painting’s Arabic title, Al Sharida, meaning ‘the mentally escaped’. This analogy of escape reflects the artist’s disillusionment with Pan-Arabism – a political ideology that called for all Arab people to be united in a single state – in his native Egypt in the late 1960s.

Gallery label, March 2025

6/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

Hamed Abdalla, Meditation 1969

Meditation comprises an abstract representation of a human figure curled up at the base of the canvas. Abdalla used gestural brushstrokes to create what he called ‘word-forms’ and a blow-drying technique to produce a crackling effect, adding sculptural depth to the textured grey background. This painting combines Abdalla’s interpretation of Arabic calligraphy with the material experimentation of CoBrA artists, with whom he became involved in Copenhagen. The group, including Pierre Alechinsky and Christian Dotremont, displayed nearby, aimed to bridge the abstraction-figuration divide while celebrating spontaneous creation.

Gallery label, March 2025

7/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

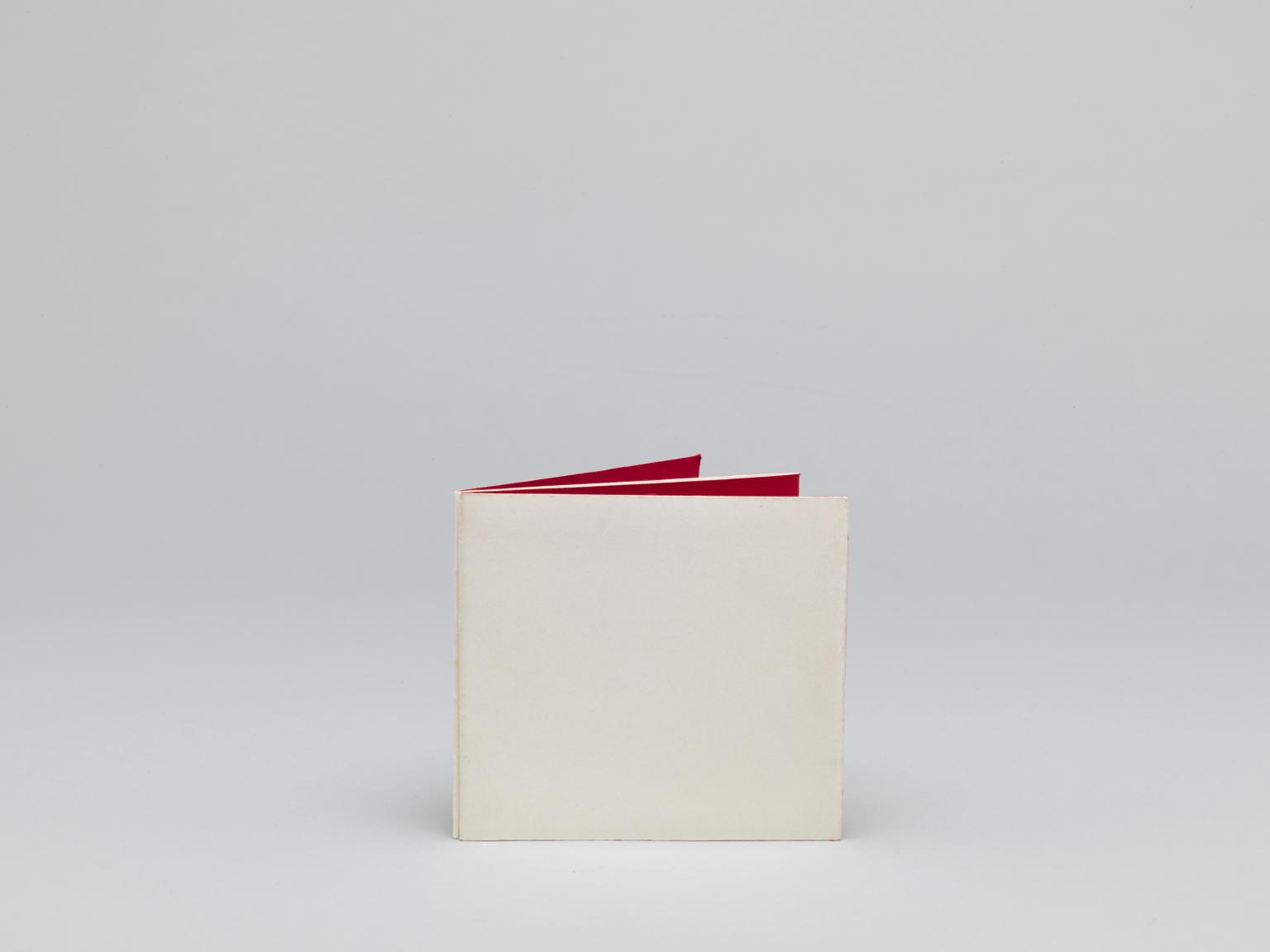

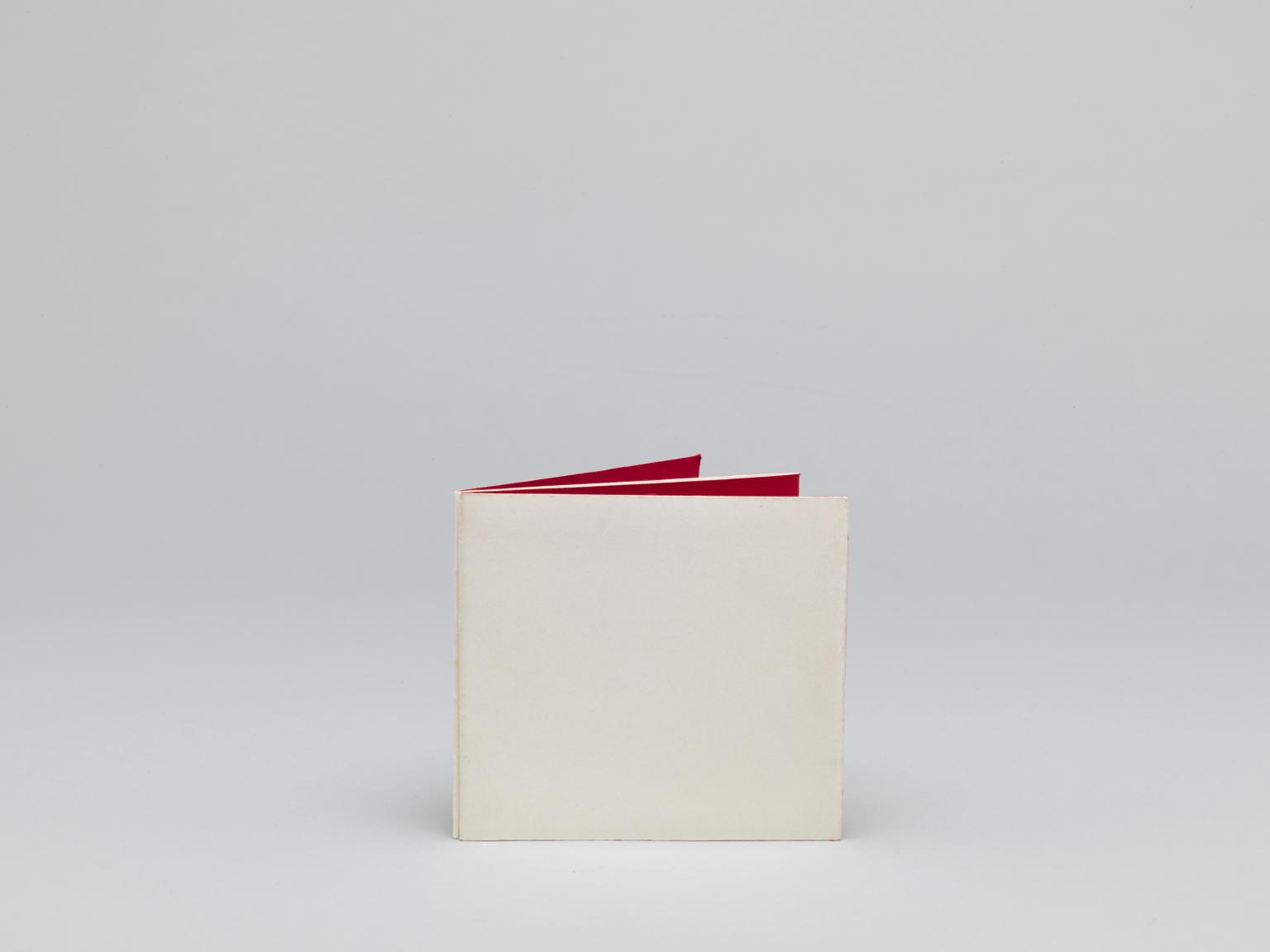

Li Yuan-chia, Calligraphic Book 1963

Calligraphic Book is a prime example of what Li Yuan-chia referred to as ‘Cosmic Points’. These points symbolise the beginning and end of all things. They often appear as simple calligraphic marks, dots of colour, or punctures in the paper. The Cosmic Points explore ideas of infinite space, relativity, and the delicate balance between stability and fluidity. As Li suggested: ‘If you can really understand it, you will feel indeed the great life of the universe and the value of your existence.’

Gallery label, March 2025

8/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

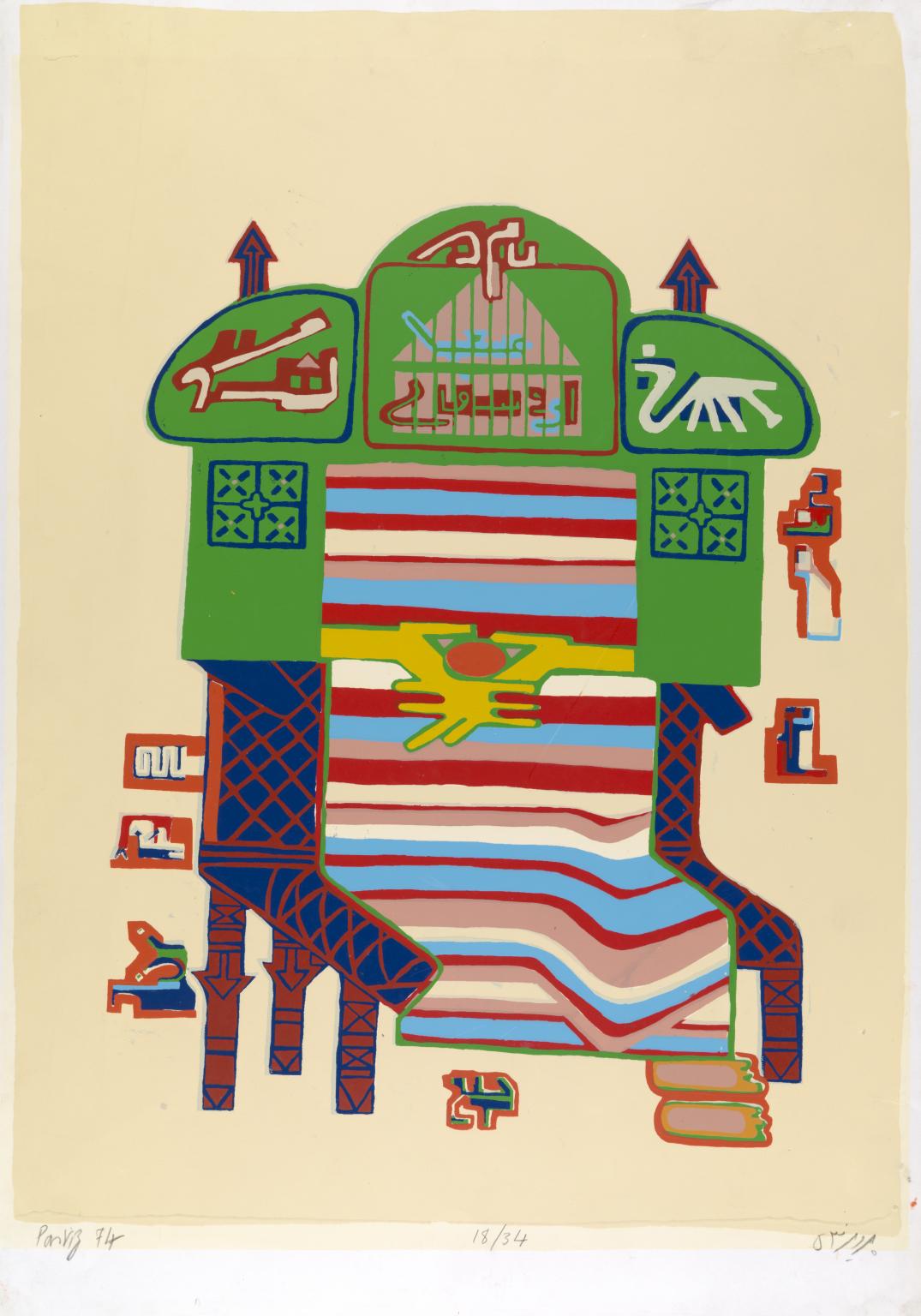

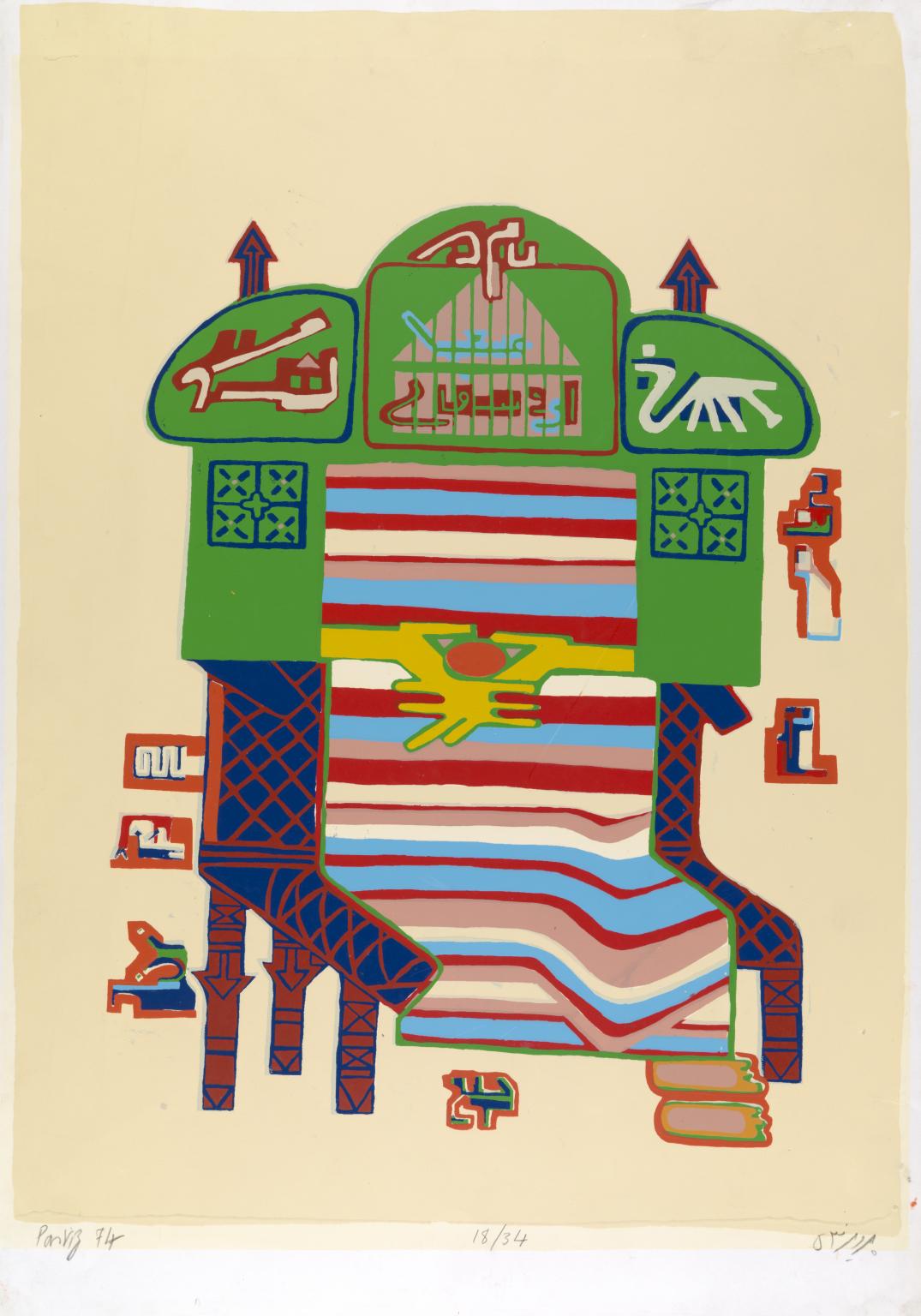

Parviz Tanavoli, Poet Squeezing Lemon 1974

Returning to Iran from Europe in the 1960s, Tanavoli encountered the country’s resistance to western figurative art. He began incorporating symbols, colloquialisms, and calligraphic elements into his work. Tanavoli’s extensive collection and research on Iranian artefacts, such as carpets, richly inform his artistic output. An avid collector, he was also interested in locks, objects believed to have protective powers, and religious posters. The fragmented forms in his prints often originate from these objects. Many of Tanavoli’s works reference Persian poetry and popular religious practices.

Gallery label, March 2025

9/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

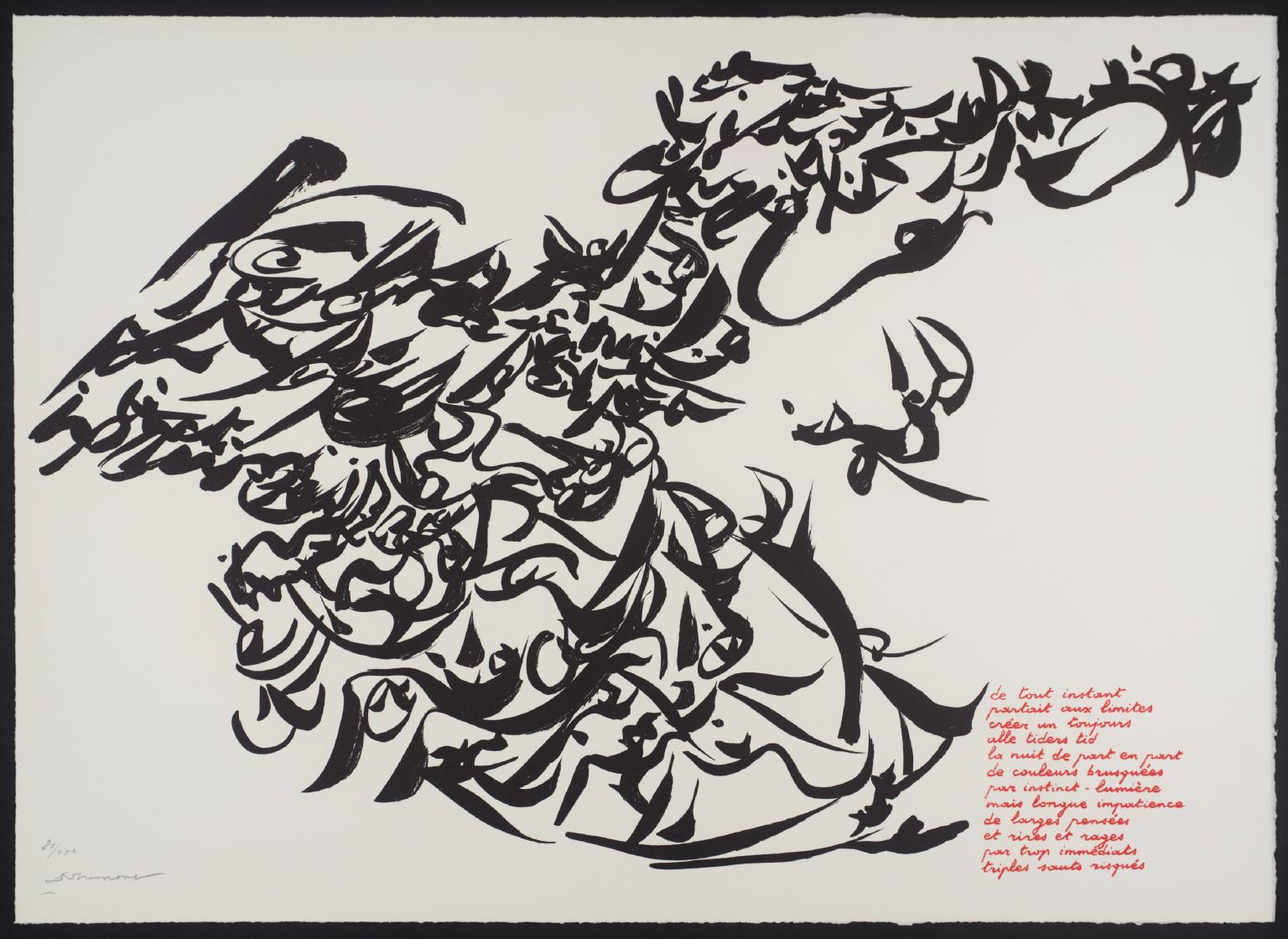

Christian Dotremont, [no title] 1975–6

This work reflects Dotremont’s interest in the relationship between written language and visual arts. In the 1950s, he created word paintings with Pierre Alechinsky, who was also part of the CoBrA group. It exemplifies his style of ‘logograms’ or drawings meant to achieve the ‘unity of verbal-graphic inspiration’. These freely drawn poems are divorced from the need for readability or legibility of writing. He looked to Sumerian, Japanese, Arabic, and Indian scripts to balance drawing and writing. The bottom right corner of the page features a poem, while the rest of the space is dedicated to the visual counterpart of the text.

Gallery label, March 2025

10/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

Mark Tobey, Northwest Drift 1958

Northwest Drift is a meditative response to Seattle’s grey and hazy landscape. Yet, as Tobey once remarked, ‘The Orient has been the greatest influence’ of his life. In 1918, he converted to the Baha’i faith and sought to explore the spiritual in his art and an alternative to surrealism’s automatism. His interest in calligraphy began during his eastern Mediterranean trip in 1926. After studying calligraphy and practising meditation at a Zen monastery near Kyoto in 1934, he developed his signature ‘white writing’ style. Built on thousands of interlaced white lines, this technique forms a calligraphic mesh on the surface.

Gallery label, March 2025

11/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

Mohammed Melehi, Casa 1970

A common abbreviation for Casablanca, Casa features Melehi’s signature ‘wave’ motif, partly inspired by the curves of Arabic calligraphy. Its dynamic, flame-like composition evokes a cityscape. As a professor at the Casablanca Art School (1964–69), Melehi sought to decolonise its academic framework, looking to other interdisciplinary models like the Bauhaus. Alongside Farid Belkahia, Mohammed Chabâa, and others, he developed a modern abstract language by reclaiming Morocco’s visual heritage. Casa also reflects the influence of abstract painting trends from New York, where Melehi lived in the early 1960s.

Gallery label, March 2025

12/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

André Masson, Kitchen-maids 1962

In the mid-1920s, Masson joined surrealist artists who pursued psychic automatism, a technique to express creativity without conscious control. Masson’s 1923 automatic drawings foreshadowed the group’s founder André Breton’s later manifesto on automatic writing. Kitchen-maids exemplifies this process with its loose squiggles reminiscent of east Asian calligraphy. Masson was well-versed in Chinese calligraphy and was particularly fond of Thuluth script. This work’s script-like lines and sense of an all-over aesthetic echo the ink ‘calligrams’ Masson created in the 1940s using a bamboo pen.

Gallery label, March 2025

13/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

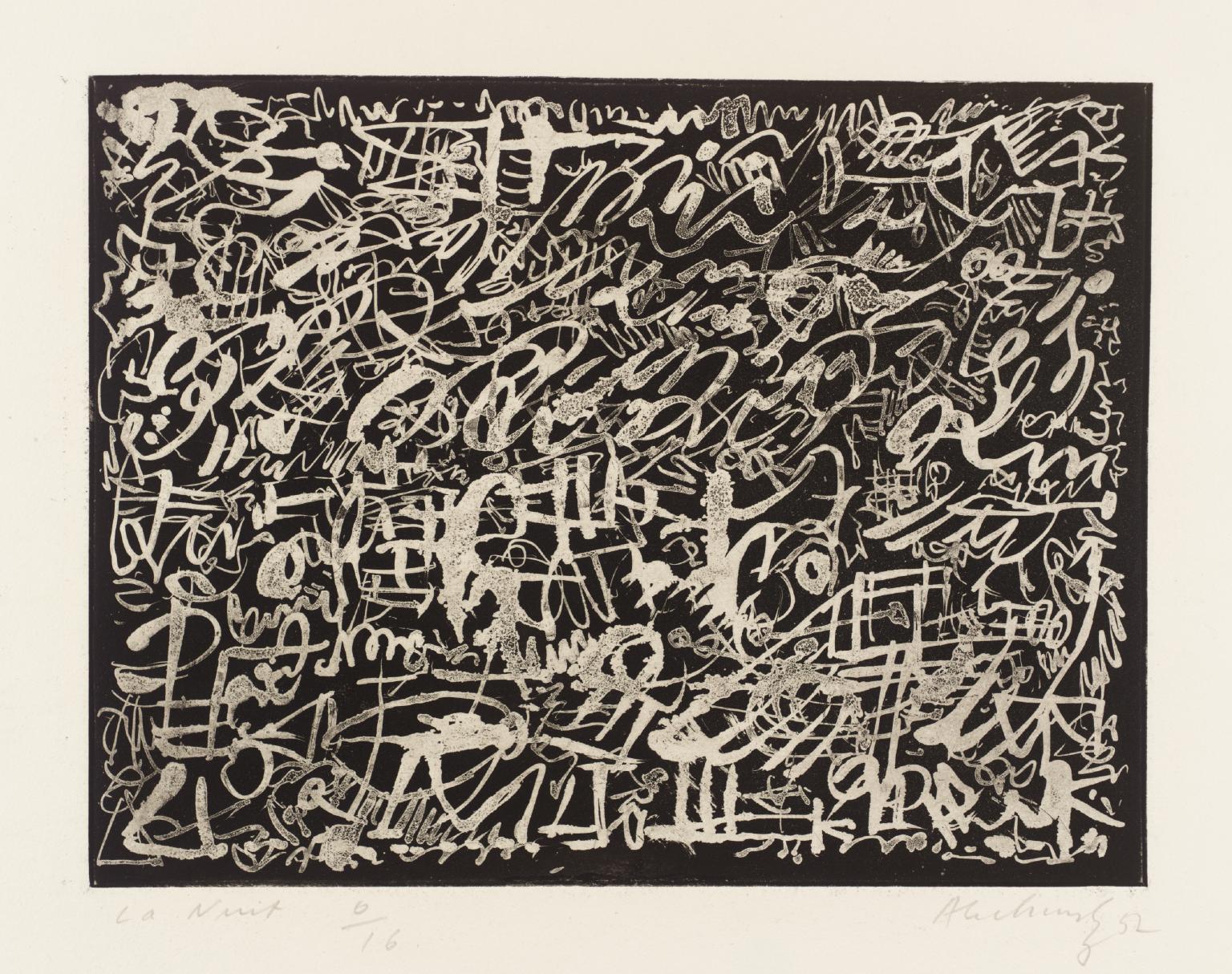

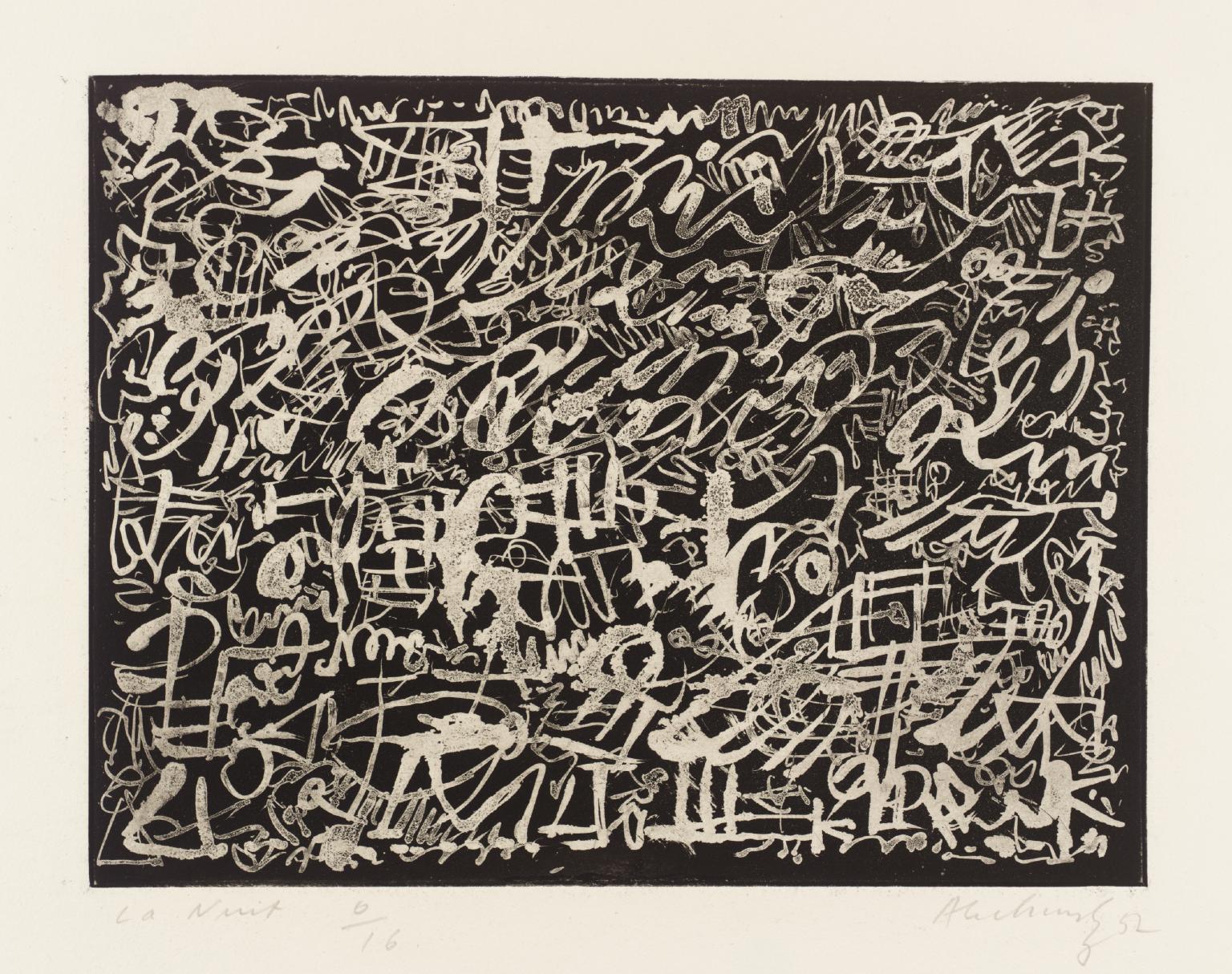

Pierre Alechinsky, The Night 1952

Alechinsky was a prominent figure in the CoBrA artist group, known for their fondness for handwriting in art. He also admired the fluid brushwork and gestural freedom of Japanese calligraphers. With its twists of white on black, The Night evidences the impact of East Asian calligraphy on his practice as he moved between brush to pen and created his works directly on the floor. Alechinsky also collaborated with Christian Dotrement, shown nearby, on works that directly reference the visual structures of manuscript paintings.

Gallery label, March 2025

14/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

Parviz Tanavoli, Poet and Bird 1974

Returning to Iran from Europe in the 1960s, Tanavoli encountered the country’s resistance to western figurative art. He began incorporating symbols, colloquialisms, and calligraphic elements into his work. Tanavoli’s extensive collection and research on Iranian artefacts, such as carpets, richly inform his artistic output. An avid collector, he was also interested in locks, objects believed to have protective powers, and religious posters. The fragmented forms in his prints often originate from these objects. Many of Tanavoli’s works reference Persian poetry and popular religious practices.

Gallery label, March 2025

15/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

Li Yuan-chia, Untitled c.1954–61

Hailed as a ‘visual philosopher’, Li Yuan-chia was interested in questions of how art can reflect our place in the universe and help us live. He is known for his ‘Cosmic Point’ compositions, which contain a dot or small circle to symbolise both personal and universal significance. In 1956, he founded the Ton Fan Collective with seven other artists, as he engaged with the longstanding practice of ink painting. These works invite viewers to find their own meaning. They ‘can mean all or nothing to you’, as the artist noted: ‘The simpler a thing is, the more likely it is to be misinterpreted or even dismissed.’

Gallery label, March 2025

16/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

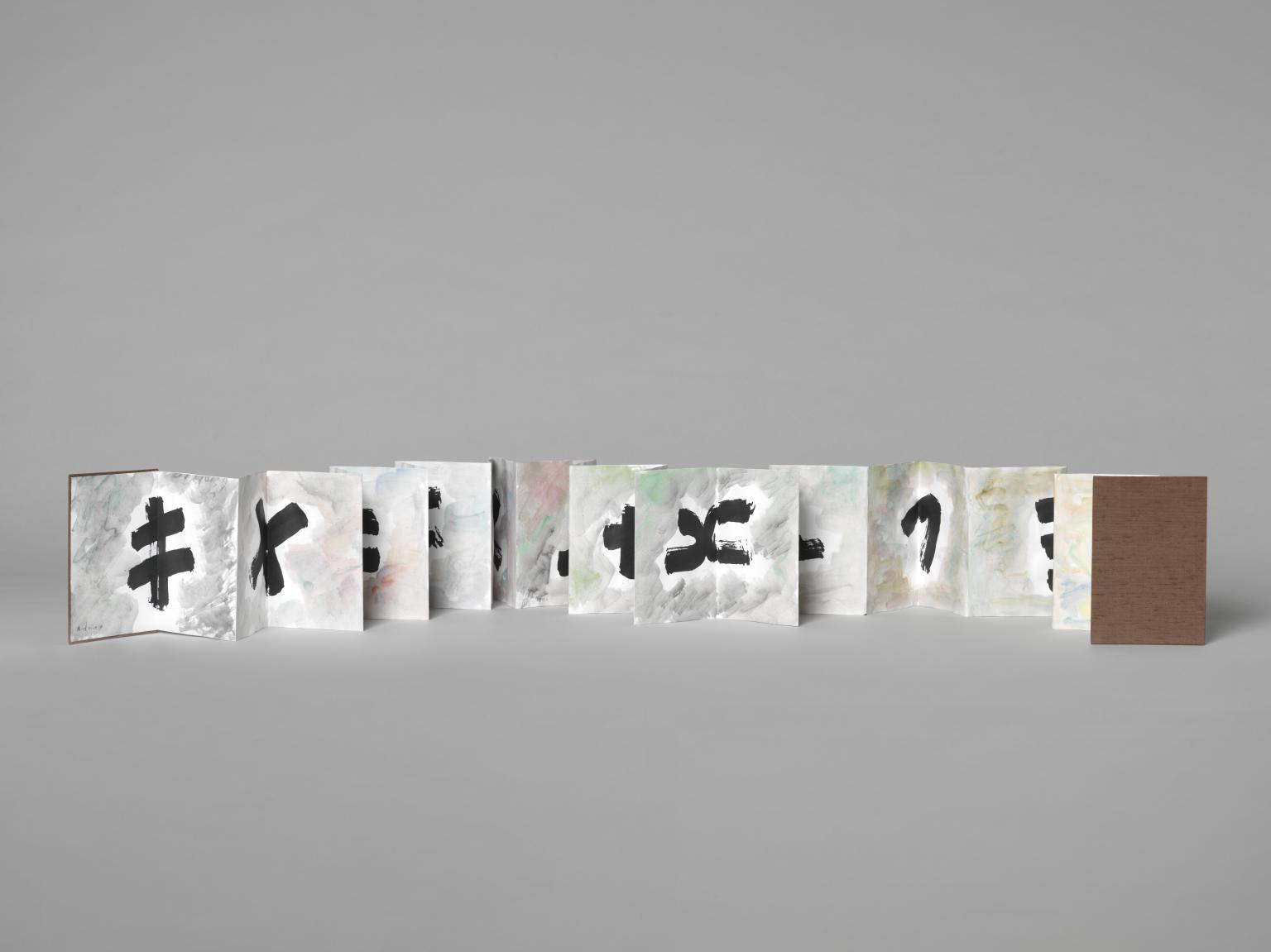

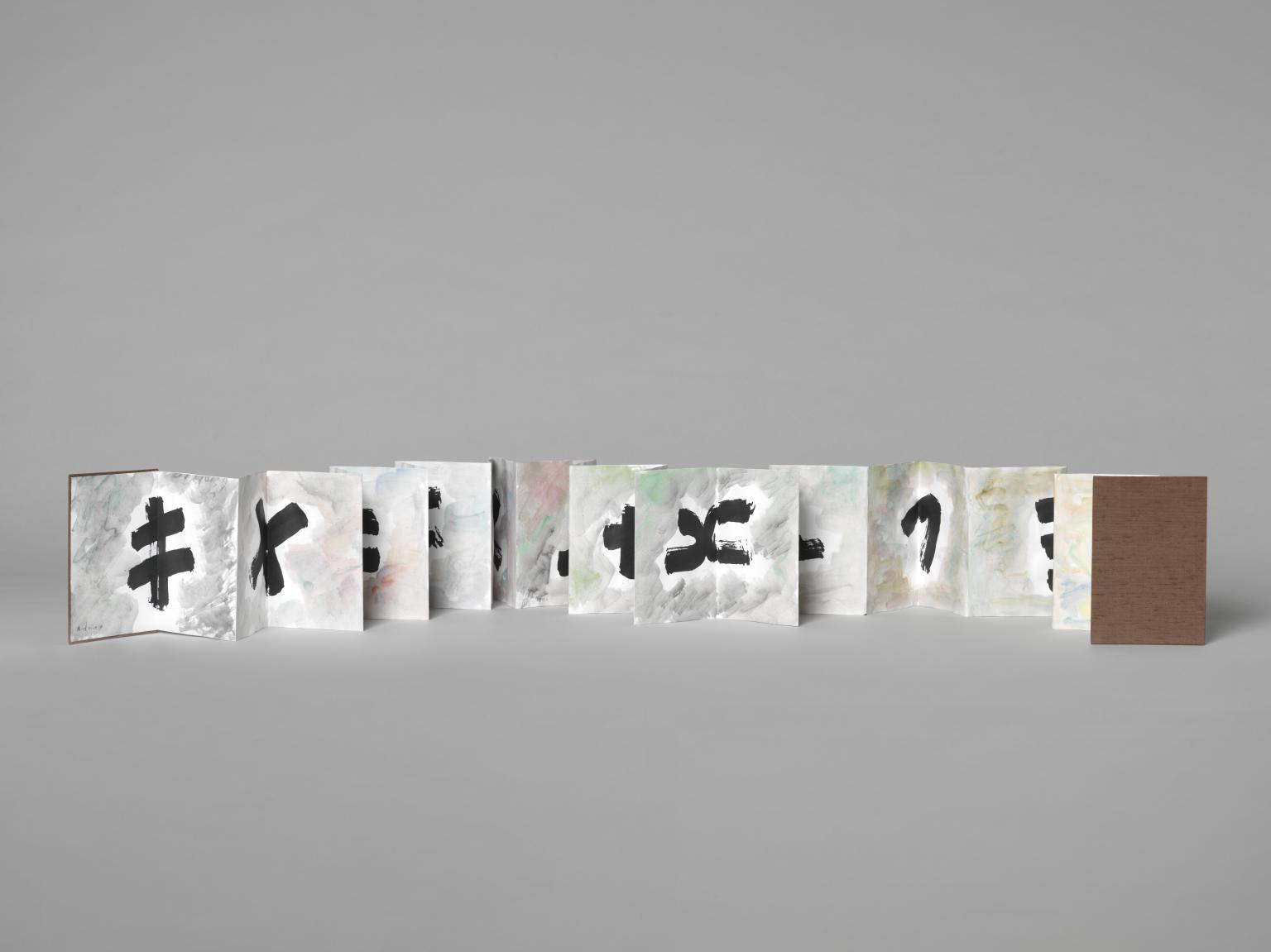

Etel Adnan, Key Signs 2017

Key Signs is one of several leporellos – accordion-pleat folding books – created by Adnan. She described working in this format as ‘like writing a river’, linking abstract painting to written expression. The work becomes a vibrant, expansive landscape when open but closes into a small notebook. It symbolises Adnan’s transcultural journey from her Lebanese-Syrian beginnings to her later life in California and Paris from the 1950s onwards.

Gallery label, March 2025

17/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

Saloua Raouda Choucair, Poem of Nine Verses 1966–8

In the early 1960s, Choucair began creating what she called ‘sculptural poems’ using interlocking forms that can be rearranged in various formations. Poem of Nine Verses is influenced by Sufi poetry, Islamic and modernist architecture, and geometric abstraction. Each aluminium piece can stand alone, like a verse in a poem, but also forms a unified structure. In creating this work, the artist ‘wanted rhythm like the poetic meter, to be at once more independent and interlinked, and to have lines like meanings.’

Gallery label, March 2025

18/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

Ibrahim El-Salahi, Untitled 1967

El-Salahi combines African and Arab cultural motifs with elements of Arabic calligraphy. Here, strange animal and plant-like forms, faces, and skeletons emerge from the broken calligraphic lines and morph into mask-like, totemic figures. In the wake of Sudan’s independence from colonialism, El-Salahi looked to his local environment for inspiration. He developed a distinctive visual language later identified as the ‘Khartoum School’. He stated, ‘I wrote letters and words that did not mean a thing. Then ... I had to break down the bone of the letter’.

Gallery label, March 2025

19/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

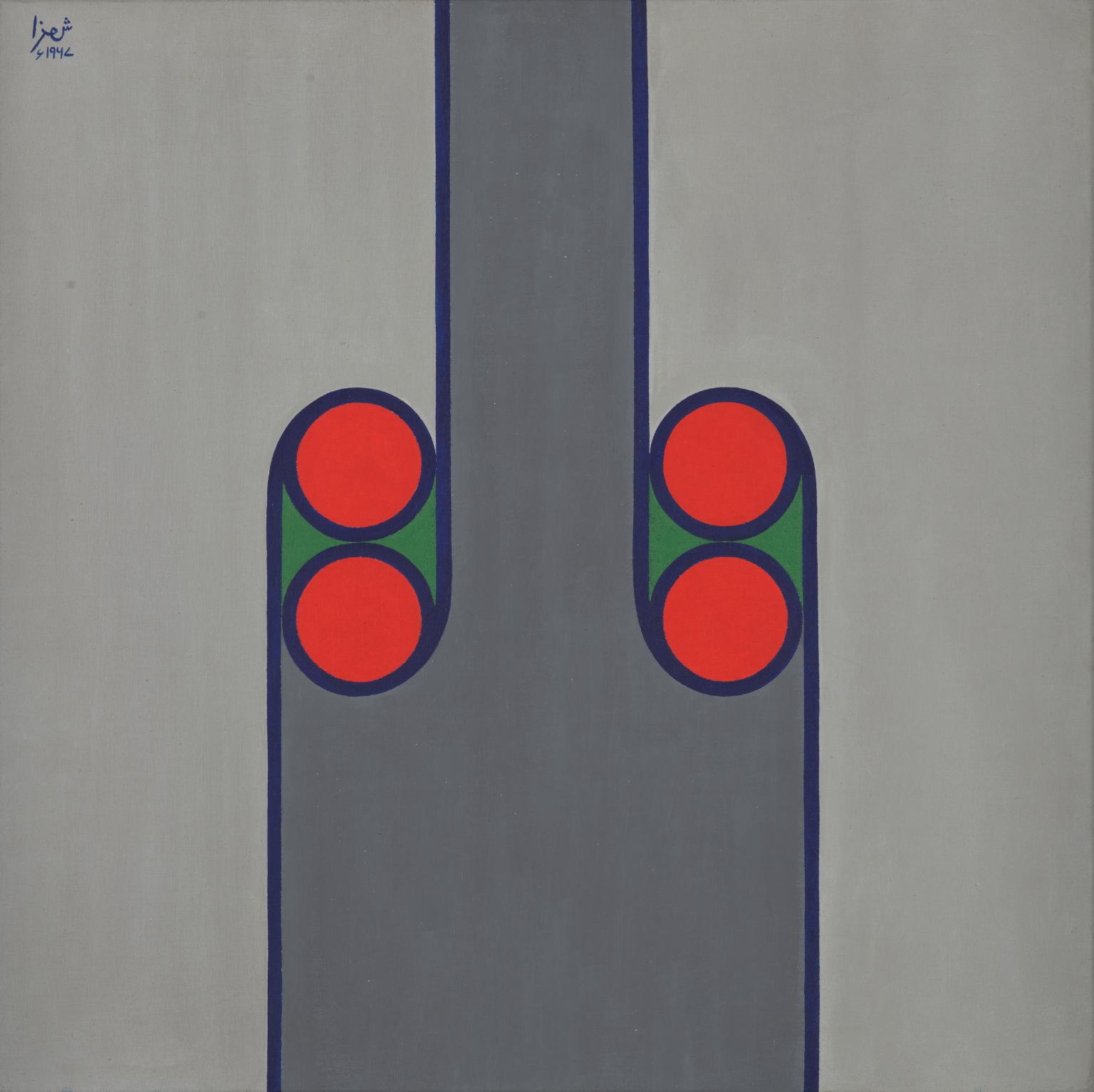

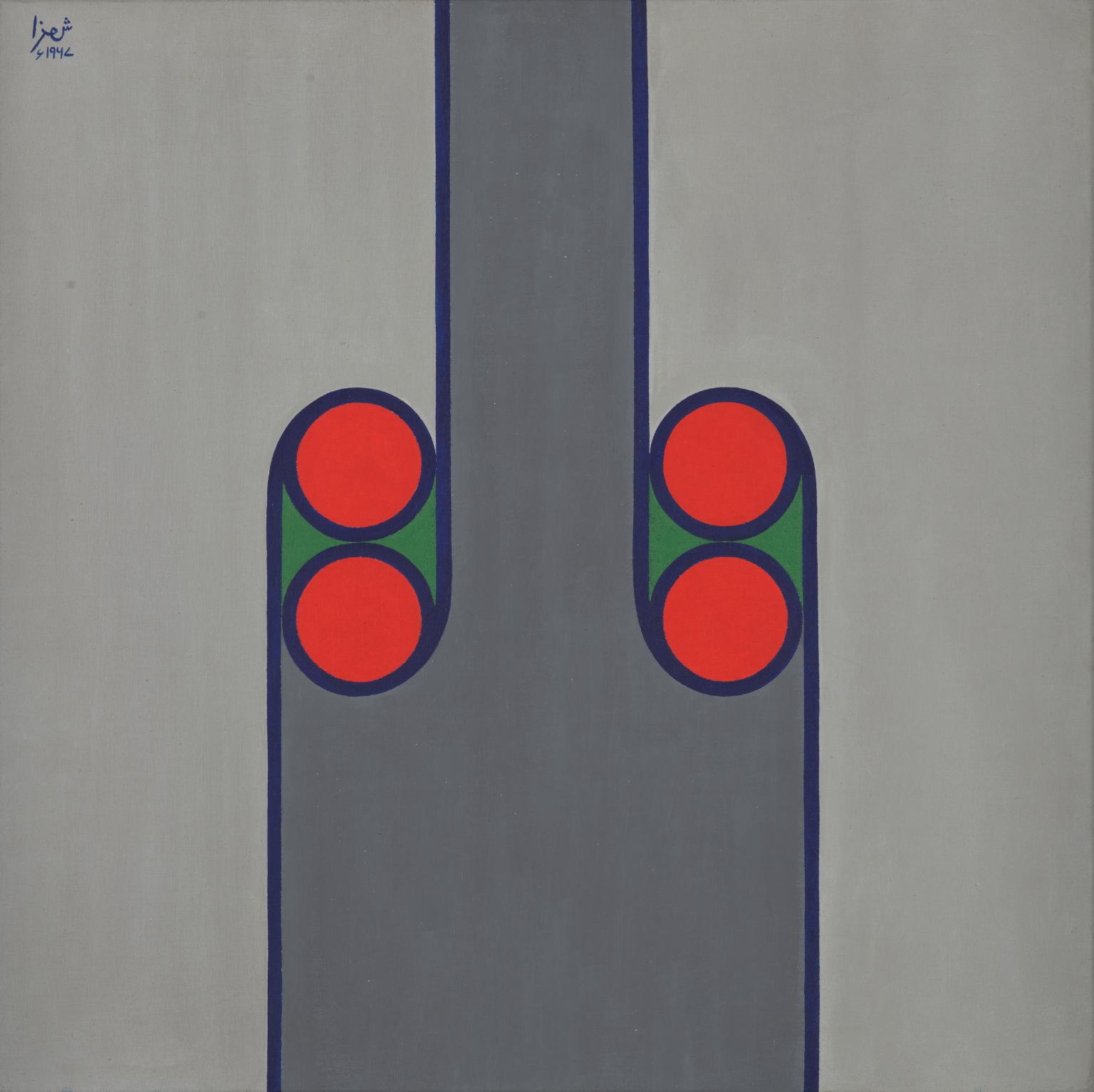

Anwar Jalal Shemza, Meem Two 1967

Shemza’s practice is built on the geometry seen in Indian textiles and Islamic architecture from the Mughal Empire found throughout Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. He uses circles and squares to create infinite configurations inspired by Arabic and Persian calligraphy. Shemza said, ‘My work is based on the simplification of the three-dimensional solid, architectural reality of the decorative element of calligraphy.’ Meem Two references the letter meem in Urdu (M in English), the basis for a series of compositions made in the 1960s.

Gallery label, March 2025

20/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

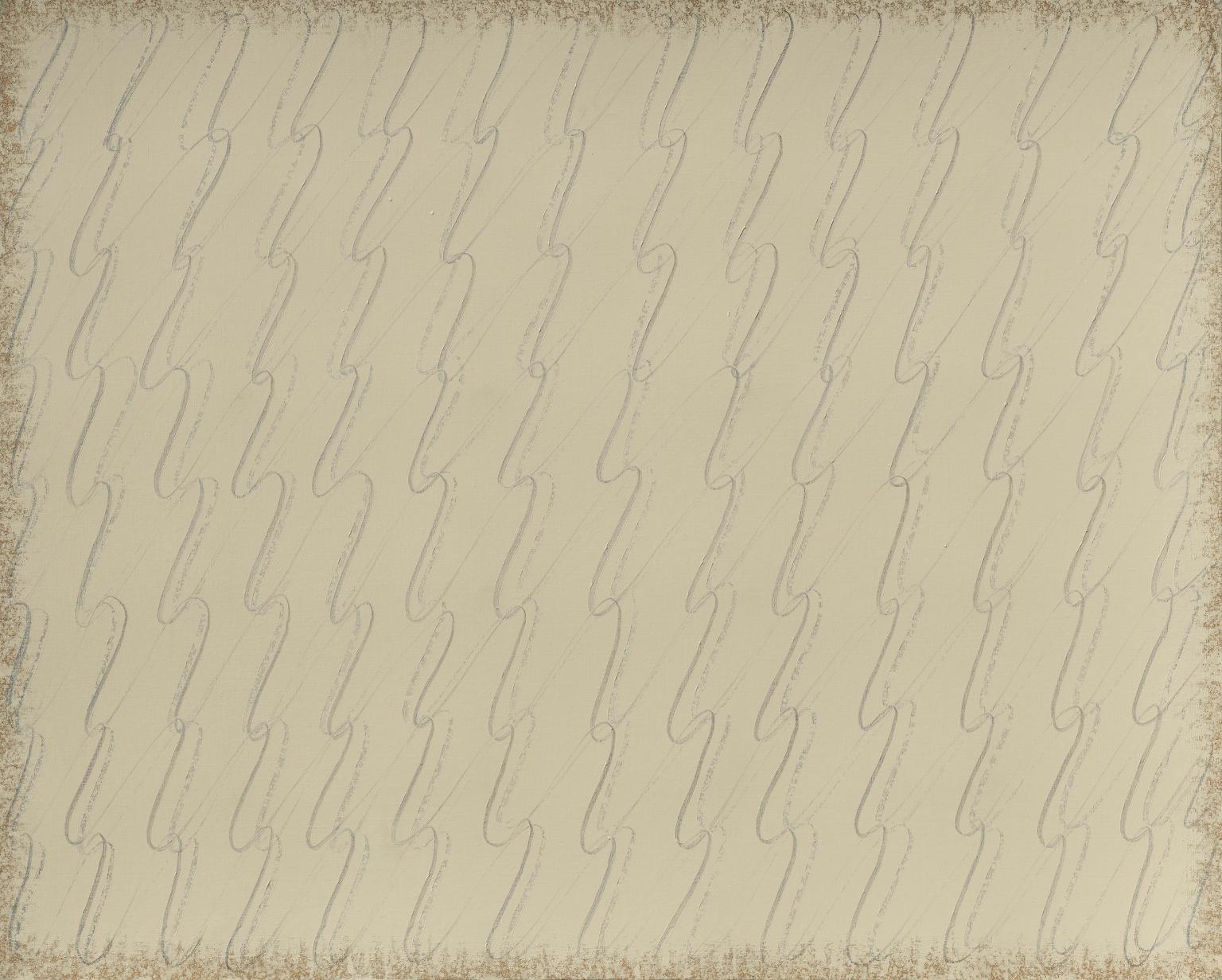

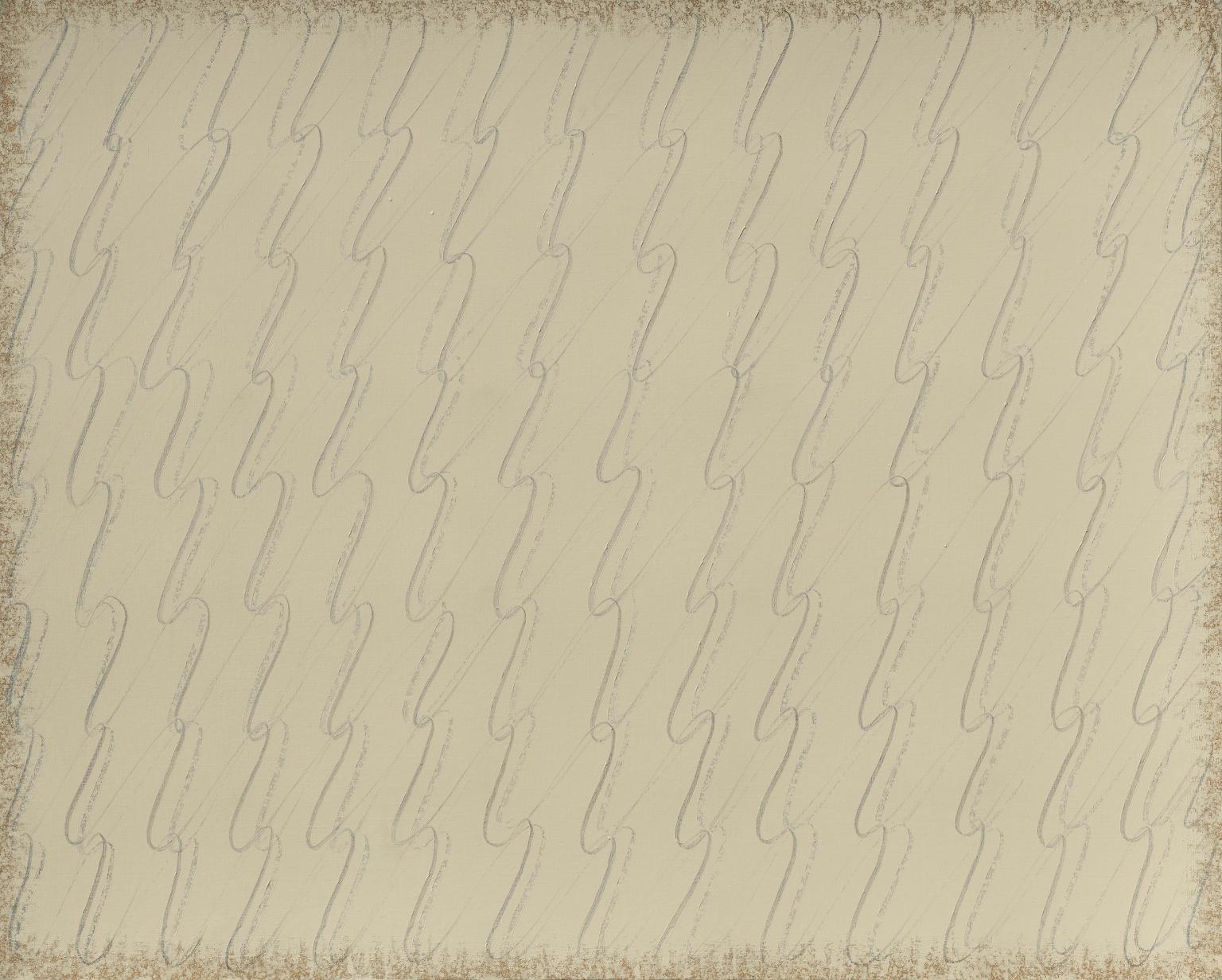

Park Seo-Bo, Writing No. 35-78 1978

21/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

Paul Klee, Ships in the Dark 1927

Gallery label, March 2025

22/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

Li Yuan-chia, Untitled c.1954–61

Hailed as a ‘visual philosopher’, Li Yuan-chia was interested in questions of how art can reflect our place in the universe and help us live. He is known for his ‘Cosmic Point’ compositions, which contain a dot or small circle to symbolise both personal and universal significance. In 1956, he founded the Ton Fan Collective with seven other artists, as he engaged with the longstanding practice of ink painting. These works invite viewers to find their own meaning. They ‘can mean all or nothing to you’, as the artist noted: ‘The simpler a thing is, the more likely it is to be misinterpreted or even dismissed.’

Gallery label, March 2025

23/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

Li Yuan-chia, Untitled c.1954–61

Hailed as a ‘visual philosopher’, Li Yuan-chia was interested in questions of how art can reflect our place in the universe and help us live. He is known for his ‘Cosmic Point’ compositions, which contain a dot or small circle to symbolise both personal and universal significance. In 1956, he founded the Ton Fan Collective with seven other artists, as he engaged with the longstanding practice of ink painting. These works invite viewers to find their own meaning. They ‘can mean all or nothing to you’, as the artist noted: ‘The simpler a thing is, the more likely it is to be misinterpreted or even dismissed.’

Gallery label, March 2025

24/24

artworks in The Shape of Words

Art in this room

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

![P03247: [no title]](https://media.tate.org.uk/art/images/work/P/P03/P03247_10.jpg)

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

You've viewed 6/24 artworks

You've viewed 24/24 artworks