HOLLY CONNOLLY

In 1991, during a three-week residency at the Banff Centre for the Arts in Alberta, Canada, the artist Helen Chadwick (1953– 1996) set out in the freezing cold with her collaborator (also her new husband) David Notarius. Together, they piled snow up into mounds, pressing a giant, cookie cutter-style mould over each mound to press it into a flower-shaped chunk. They took turns pissing straight into the snow. But snow, of course, doesn’t last. To make, or you could say ‘to preserve’, the physical, final Piss Flowers that you see on these pages – pieces which can be considered both artworks in their own right and evidence of the process of their creation – plaster was poured into the tracks that the piss had forged in the snow.

These plaster forms were later shipped to the UK, where they were cast in bronze and lacquered in white enamel, resulting in the 12 flowers that have been exhibited globally over the past three decades, either laid out on grass outdoors or in galleries, where they are typically installed on AstroTurf (a suitably vulgar, incongruous material in a gallery setting).

The Piss Flowers, then, are negatives, or inverse records of that time in the snow. Chadwick had squatted in the centre of each mound – her piss forms the proud, protracted jets in the middle of each flower – while Notarius’s is dribbled concentrically around hers. This is often read as a subversion of gendered symbols: Chadwick’s piss creating the phallic form. The flowers also mark the artist’s move away from using images of her own naked body in her work towards a practice more centred around what the body produces. ‘I want to catch the body at the moment when it’s about to turn,’ she once said. ‘Before it starts to decay, to empty.’

For me, though, more than anything else, Piss Flowers is a tribute to coupledom. Chadwick and Notarius had met in Texas in 1990, and within a year they were married and living together in Beck Road, London. The flowers were produced during that time, and they capture the excitement, exploration and sometimes disgusting intimacy of early love – a period that is precious, in part because you can’t hold on to it, because it always eventually fades, like melting snow.

Holly Connolly is a writer based in London. Her work has appeared in the London Review of Books, the Paris Review, ArtReview and the Financial Times, among others.

Helen Chadwick and her partner David Notarius making the casts for Piss Flowers during a residency at the Banff Centre for the Arts in Alberta, Canada in 1991

© The Estate of Helen Chadwick. Photos: Monte Greenshields, 1991 © Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Courtesy the Estate of Helen Chadwick, Leeds Museums & Galleries (Henry Moore Institute Archive) and Visual Arts photograph collection. Paul D. Fleck Library and Archives, Banff, Alberta

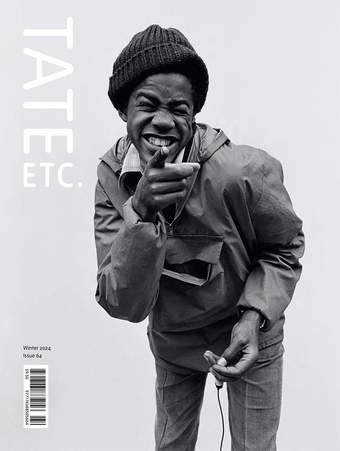

COSEY FANNI TUTTI

In the late 1970s, Helen lived opposite me on Beck Road in Hackney. I’d go over to see her and we’d sit upstairs – her studio was downstairs – and talk. She was a wonderful, supportive friend. As artists, we both worked so differently. I was completely spontaneous, whereas she was so meticulous. Her work was a celebration of her fascination with everything to do with life. It was all about discovery – of herself, the world around her, the physical, the metaphysical – and the way she expressed that, and then manifested it, was like nothing I’d seen before or since. Her whole being was in her work. I think that’s what I love about everything she did: they’re all instilled with Helen.

The first time I saw Piss Flowers, in the early 1990s, wasn’t in a gallery but on the Jonathan Ross Show. She got what she expected: ‘You call this art?’ But she carried herself so well and the way she took it on board was very Helen-like. She was always just quite matter of fact: Well, why wouldn’t you like it? It’s something quite beautiful. It’s a part of us. It’s a part of our connection with the world, and our connection with each other – meaning between her and her partner David.

Piss Flowers also speaks to me about humour. Helen was particular about getting things so that they felt and looked right, but she wasn’t precious. Her irony and humour were part of how she saw things. The beauty of things. To me, everything Helen did just screamed beauty.

As far as I’m concerned, Piss Flowers is a work of love. And part of love is humour and being able to laugh together and be together – it’s sexual, it’s everything.

Cosey Fanni Tutti is an artist and musician who lives and works in Norfolk.

Helen Chadwick

Piss Flowers 1991–2

© The Estate of Helen Chadwick. Photo © Tate (Seraphina Neville)

SYLVIA LEGRIS

Hyacinthoides non-scripta

1—

An over-complex soil map – chernozemic, clay-dense,

bole brown foundation of grassland vegetation – under an old-snow tonal structure, a long-season shorthand harmonic,

of lung-light hyacinth, of ammonia-heady under-mulching.

2—

Temperature inversion renders the air an iced wordlessness,

the earthbound made extraterrestrial. The formerly floral

is cold-zoned, an overwintering pulse.

3—

Midwinter’s glassy cast. Vitreous, a storm of enamelled flakes.

A mutable materiality. The cold skin of January.

4—

The subnivean raises the muffled bluebell. The surface unscripted. An off-the-cuff respiration, a mixed ice vapour.

5—

Snow overwritten with sun, wildflower effluvia, goldenrod, prairie sunflower, buttercup ...

Unseasonable rain, pissing cold, an improvised nutrient flow – nitrogen, potassium, phosphorus.

A botanical metabolism, yellow flowers on snow,

a garden of wild on white.

Sylvia Legris is a poet who lives in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Her latest collection is The Principle of Rapid Peering, published by Corsair.

Helen Chadwick and David Notarius take turns urinating into a mound of snow topped with a metal, flower- shaped template

© The Estate of Helen Chadwick. Photos: Monte Greenshields, 1991 © Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Courtesy the Estate of Helen Chadwick, Leeds Museums & Galleries (Henry Moore Institute Archive) and Visual Arts photograph collection. Paul D. Fleck Library and Archives, Banff, Alberta

ANYA GALLACCIO

When I was studying at Goldsmiths during the mid-to-late 1980s, Helen Chadwick was one of the very few contemporary women artists whose work I had seen in the flesh. While her art is always initially beautiful, on closer inspection it is alienating, ambiguous. She presented the actual stuff of a body, making visible the mutability of life.

Carcass, her huge, glass tank of vegetable waste, first shown at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1986, was significant for me. What began as distinct layers of material turned into coloured bands that blurred and eventually dissolved into each other. Seemingly made as a stable, formal composition, the artwork later exploded, which was, technically, a disaster. But from my perspective – by releasing the foul smell of decay, staining the space – it took Carcass from being an image of mutability to something closer to an actual body.

To make Piss Flowers, Chadwick and her partner pissed in the snow to generate positive and negative forms. In hardware terminology, male and female parts are made to join or connect. A simple, playful – or to some, taboo – gesture, literally marking space and a moment in time, and, in so doing, directly casting reality.

Anya Gallaccio is an artist who lives and works in London and San Diego, California. Her survey exhibition, preserve, is at Turner Contemporary, Margate until 26 January 2025.

Helen Chadwick

Piss Flowers 1991–2

© The Estate of Helen Chadwick. Photo © Tate (Seraphina Neville)

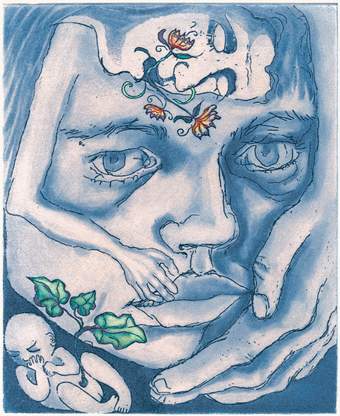

NICOLAS DESHAYES

Helen Chadwick printed depictions of the body onto various supports with light, liquid and chemical processes, producing desire-inducing imagery that draws the viewer into the darker realities of passing time. Made with forensic precision, her works exist in vitro. They propose a view of bodies pressed behind glass and confined within frames, offering us visceral natures mortes in high definition.

In Piss Flowers – a body of work that has shaped me significantly as a sculptor – Chadwick imprints her and her partner’s body into material. Abandoning figuration, the sculptures are nonetheless wholly corporeal by their means of making: using their own urine as the acid etch in blocks of snow, trickles and jets carve into the material like a hot knife in butter. In a form of molybdomancy, as if divining the future by flinging molten metal into cold water, they are cast into plaster and then bronze. The mould is broken away to reveal a detailed topography of the urine’s course; deep ravines, crests and valleys turn into erect calcified stalagmites, moments frozen in time. In an emulsion of yonic and phallic, they are sexually charged but without assigned gender. The use of bronze recalls bubbling terrestrial magma, pushing through the Earth’s crust in an efflorescence of rock, but the white enamelled coating reminds me of sanitaryware, I want to lick it and sit on it, but it might hurt.

In these works, there is no real measure of scale. Their precise arrangement at once carries the reverence of gonshi, Chinese scholar’s stones placed upon their lacquered pedestals, the allure of melting meringues left out in the rain and a parterre of flowers on a manicured lawn.

As a viewer I feel disembodied, tiny, like I’m high up looking down onto a solar system, surveying a dissection, a landscape, a pattern of cells. Suddenly I am a bumblebee, gliding through a corolla, sitting upon a pistil. Drunk on pollen I delve down into the bacterial flora, deep into the cloaca, elbowing my way through heavy corridors of flesh with my headlights on. Then I am inside my own body, following a course mapped by a photosensitive dye, it’s internal contours bulbous and glossy under infrared light. I feel like I’ve been turned inside out, the inner walls of my termite mound exposed for all to see, my extremities fizzing like polystyrene doused in white spirit. As I come to, emerging back into the world, I rub my eyes – phosphenes of colour float over my retinas and merge with the landscape beyond.

Nicolas Deshayes is an artist based in Dover. His text is taken from the forthcoming book Helen Chadwick: Life Pleasures, published by Thames & Hudson to accompany a major exhibition of the artist’s work at The Hepworth Wakefield, 17 May – 27 October 2025.

ARTIST ROOMS: Helen Chadwick, Tate Modern, until 8 June 2025.

Piss Flowers presented as part of the D.Daskalopoulos Collection Gift, a group of over 110 contemporary artworks donated to Tate in 2023.

ARTIST ROOMS is a touring programme managed in partnership by Tate and National Galleries of Scotland.