Detail of a billboard installation by Nancy Willis (pictured) and Jenny Polak, Isle of Dogs, London, 1995

© Nancy Willis. Courtesy the artist

To celebrate Women in Revolt! at Tate Britain, we invited nine women to discuss their experiences of making feminist art in 1970s and 1980s Britain, and the social and artistic barriers they fought to overcome.

In the first conversation, we hear how Bhajan Hunjan and Nancy Willis tackled the question of how to represent women who have been excluded from or misrepresented in art. Nancy talks about finding her voice through her making and by putting on trailblazing exhibitions with other disabled women artists. Meanwhile, Bhajan recalls her mother’s admission that she didn’t understand Bhajan’s art and how that made it a ‘necessity’ for her to make works that spoke to, and about, the real women she was working with in a refuge for South Asian women in Reading.

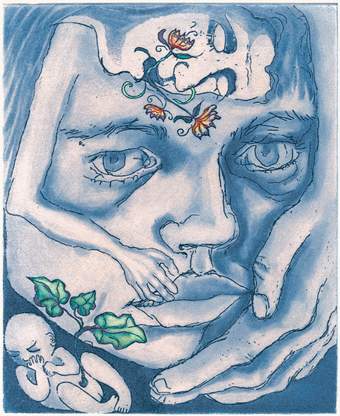

Nancy Willis

Self Portrait IV 1983

Pastel on paper

70 × 50 cm

© Nancy Willis. Courtesy the artist

LINSEY YOUNG Could you begin by talking about how you came to make the works included in Women in Revolt?

BHAJAN HUNJAN In 1982, I started working at a South Asian women’s refuge in Reading. When I came home, I would think about these women’s lives, and I began to feel that I should do something that reflected my thoughts about the women I was working with.

Around that time, I would go to Kenya every year to see my family and take images of my work. That was when my mother said: ‘What’s your work about? I don’t understand your work, you know.’ That was interesting.

Returning to Reading, I had a studio in a little attic, and I think I was able to make the shift to making figurative work because it was a private space. Obviously, I was aware of a lot of other figurative women artists, such as Frida Kahlo, Gwen John, Käthe Kollwitz, who were important role models. And then suddenly portraits of women became the thing I worked on. It almost felt like a necessity to me when I started doing those portraits.

LY It’s interesting that you use the word ‘necessity’, because it seems to me that for most of the artists in Women in Revolt!, their work has come through necessity. There’s a fight, or a struggle, or a position that the artists want to communicate. Nancy , does that echo with some of the work that you were making at a similar time?

NANCY WILLIS Yes, it does. When I was at art school, I wanted and needed to learn about how to make art, but I had no idea what to make my art about. It was after some years of working quietly on my own that I realised I needed to make more personal work about my experience of being a disabled woman. And that happened in the early 1980s, when other disabled artists were saying: ‘What’s going on here, why doesn’t our artwork have a place to be seen?’ It was amid the Black and Feminist Art Movements that the Disability Arts Movement got started.

LY But you were also driving things forward – you made some of the earliest exhibitions around disability arts.

NW Yes, the first one was called 1982 AD, A Festival of Artists with Disabilities. I got together with some other disabled artists who had somehow managed to struggle through the arts education system. We discovered that we needed to liberate ourselves, as well as to reach out to other unrecognised disabled artists who were quietly creating artwork, hidden away in institutions and day centres. It was a bad winter, and I remember driving through the snow to places like the Royal Hospital and Home for Incurables and discovering the breathtaking artwork that had been going on there. It was so exciting. That was just the beginning of a series of groundbreaking exhibitions and events.

LY It’s important to me that this trailblazing work is recognised. I thought of disability arts in the UK as starting from 1990 onwards, but it blew my mind when you told me about those exhibitions. I really want that updated in the history books. One of the things that strikes me about your two early portraits is that they’re incredibly sensual… They’re quite sexy!

NW You might be the first person that’s said that! I had just fallen in love at that time, so maybe that was showing through and inspiring those early self-portraits – I was finding my own voice.

I needed to create work that had nothing to do with the images being made by able-bodied people about disability, such as charity advertising, where we were often portrayed in a negative, pitying way.

Bhajan Hunjan

The Affair 1987–8

Acrylic paint on canvas

112 × 50 cm

© Bhajan Hunjan. Courtesy the artist

BH Picking up on what Nancy was saying about representation, I hadn’t seen images of strong South Asian women in the media. They were always vulnerable, charity advert kinds of images. I wanted my women to say, ‘I’m here, and whether you respect me or not, I’m dignified’. In my painting The Affair 1987–8, the woman is looking out, with her inner strength, and is somehow creative. She is at a cusp where she’s just about to cross a border, or boundary. I think we are trying to cross those restrictions, those boundaries, every day, where we find a new self.

LY Could you talk about what the physical experience of making means, or has meant, in your life?

NW When it was easier for me to make artwork, the physical process of making was more like reliving memories of childhood freedom – running around, climbing trees, playing and fighting with my brothers. The whole physical engagement with the world of art became something that could continue those experiences, even after I started to become more disabled.

I have a disability which is progressive, so I become weaker over time. Recently it has become hard to make anything physically, but a part of me needs to keep trying. I can make art digitally, and I do sometimes. But there’s still something important to me about the physical process of making, the actual touch of materials and making marks on paper. I’ve only done one drawing this year and making that drawing was like a fight for life … I’m holding on by the skin of my teeth.

LY What has struck me while researching this show is that every artist I’ve spoken to was also involved in some sort of activism or holding down many different things at once. Could you describe the sort of work you were doing alongside making art?

NW In the late 1980s the Disability Arts Movement was an important part of disabled people’s fight for justice and civil rights. I was teaching and running workshops as a way of connecting with other disabled people. Around this time, I was asked by the Women Artists Slide Library to collaborate with feminist artist Liz Ellis on a conference about disabled women artists. It was before the days of the internet and it was a great feat, trying to discover and contact invisible or unfindable people. We kept asking each other: ‘Who have you heard of, where are they, how can we find them?’, and digging away at those connections to find disabled women artists we’d never met.

LY How do those questions about connectivity and community resonate with you, Bhajan?

BH The 1980s was, for me, a very fertile time and I was involved in a lot of collectives. Through a friend at the Slade, I met up with the Asian Women Writers Group and also got to know the women who were setting up a refuge in Reading. I was also part of Open Hand Studios, a studio group, which was largely a women’s collective. Of course, they were mostly white women. Then, in the late 1980s, I got involved with Panchayat artist collective.

Before all of that, I was part of Indian Artists UK. That’s when we organised Four Indian Women Artists, the first group exhibition ever held by women of colour. I got together with the artist Chila Kumari Singh Burman and said: ‘We’ve got this opportunity. Shall we put a women’s exhibition together?’ and she agreed. I only found two other women artists, Naomi Iny and Vinodini Ebdon, whose studios I visited near Slough and Wiltshire respectively. I wasn’t funded by anyone, I did it voluntarily. It was just so exciting to know that there were other women artists like me.

NW It was such an exciting time, discovering each other and making connections. It wasn’t only one thing happening at a time, there were little explosions all over the place.

LY Do you feel things continued at pace or did they slide away?

NW Organisations were set up in the 1990s which are still important now, such as Disability Arts Online which has been a powerhouse over the years, and two important exhibitions were held at major venues in the mid-1990s. To give some political context, after years of campaigning, the Disability Discrimination Act finally became law in 1995.

There is still a flourishing disability arts movement but I’m not sure how far we’ve made it into the mainstream. We’ve found each other, thank God, but there’s a long way to go.

BH Until the mid-1990s, there were spaces that exposed our work. But our lives were tied with the policy-making happening right at the top. In the Arts Council, certain decisions were made and funds were diverted. Important galleries, such as Horizon and Black-Art Gallery, shut down.

There shouldn’t be a hierarchical structure within the arts. It still seems that the people at the top who make it get all the funding and get bigger and bigger. They become like companies or huge brands that employ younger artists. I’ve never been picked up by a commercial gallery, so I don’t know what it feels like – maybe those artists feel under pressure to produce things. But I think collectives or grassroots organisations have a certain strength.

Generally, I think it’s healthier for communities to have lots of artists working in them. We are still lucky that in Britain that carries on, to an extent. But the austerity measures, the recessions along the way … You can’t function in an isolated way. People need to live and feed their families and support their lives. So, that’s why I went into community work and started doing public art projects. At the time we were still part of the EU, and certain funds were still coming in. That’s all gone, now. I don’t want to sound pessimistic, but it’s a struggle.

Nancy Willis

Self-portrait with Lost Baby 1988

Etching

20 × 16 cm

© Nancy Willis. Courtesy the artist

LY It’s important to not always be positive. I get irritated by institutions like ours when we wrap things up with a bow and go: ‘Oh great, we’ve done a show about feminism.’ But actually, it’s part of feminism to say that things are bad! That statement you made, that lives are tied to policy-makers, couldn’t be more accurate. Whether those be governmental policies or commercial galleries and institutions that set a standard, those things have been so harmful. A lot of what I’m trying to get at in Women in Revolt! is how capitalism affects art. To me, it doesn’t seem to do it much good.

BH When we were organising those shows, there were no curators – artists were curators. They were selecting the work of their colleagues and other artists they knew. They knew what quality was. But I think, since the mid-1990s, the curators have become the experts: they can pick people, make their careers. Where are the artists in this?

LY That’s brilliant. I’ve never thought of it that way. Abolish the curator!

BH Another thing that’s important to me is that, seeing this work from the 1980s together, we can reflect and look back. And if we can still be role models for younger people, that’s brilliant. If they can learn from where we were 40 years ago, or find it interesting, that’s amazing.

NW I agree. The works in this exhibition tell stories from a time when we were not seen. My etching Self-portrait with Lost Baby 1988 is about an experience that happened to me 50 years ago. As a child with muscular dystrophy, I had always been told that I would die young. But in my late 20s I discovered that I could live longer, even into old age. This was a shock to me! It made me so sorry that when I was 19, I had had an abortion and sterilisation, thinking that I wouldn’t be able to care for a child who also might inherit my disability. As I continued to stay alive, I became more and more distressed – I realised that I had been sterilised rather than being offered advice about contraception. Nobody even suggested that I could try to look after a child.

I made this etching in the 1980s. It will be displayed alongside a little bronze sculpture that I made of a tiny baby. It’s important to me that these pieces are shown next to each other. Together they create an expression of this terrible feeling of loss. After all this time, I feel ready to give the sculpture a name. Her name is Rosie. It’s special, after 50 years, to complete that story.

LY It’s an incredibly generous thing to allow us to show something so personal. And I know that it will resonate with a huge number of women.

NW That matters loads to me, because I know that everyone has pain and loss. It was Bhajan talking about time that made me reflect on that huge distance between now and 50 years ago. It seems like another world. Maybe our art will help make sure that people are treated differently today.

Linsey Young is Curator, Contemporary British Art, Tate Britain.

Bhajan Hunjan is an artist based between Reading and London.

Nancy Willis is an artist who explores love, loss and human vulnerability.