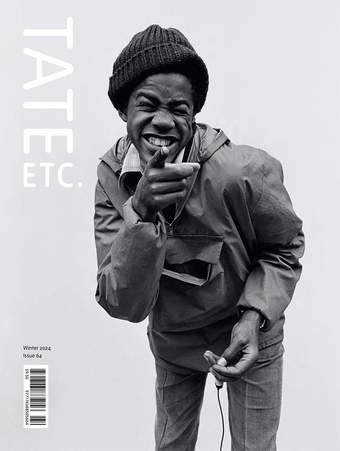

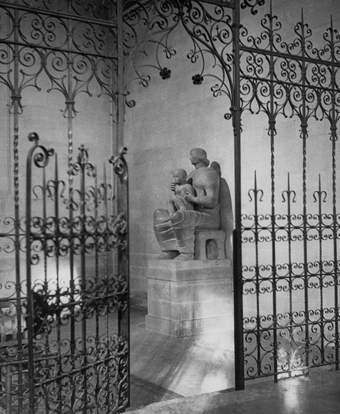

Henry Moore’s Madonna and Child 1943–4 in St Matthew’s Church, Northampton

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved, DACS/www.henry-moore.org 2024

Behind iron curlicues in an alcove of St Matthew’s Church, Northampton, sits Henry Moore’s 1943–4 sculpture Madonna and Child, carved from Hornton stone. The eponymous child faces forward, solemn, his left hand enclosed in his mother’s left fist, her right hand resting protectively against his shoulder as she looks off to the side, away from the viewer. Installed as the Second World War continued to rage (Northampton, in fact, was the location of the evacuated Chelsea School of Art), the work is part of Moore’s broader mid-century return to maternal figures as well as family groups. Maquettes for this statue and others populate a room at Tate Britain, alongside sketches of sleeping infants, clasped hands, and intertwining body parts. In biographical accounts of Moore’s life, the context for this renewed interest in maternal forms was his ongoing attempt with his wife, Irina Radetsky, to conceive a child: the couple experienced several painful miscarriages before the birth of their daughter Mary in 1946, named after Moore’s mother who had died in 1944.

Anyone who has spent any time with an infant knows how counterintuitive it feels to cast them in stone: stillness is not something necessarily associated with the wriggling babe in arms. Moore’s Madonna and Child, though, has a historic sombreness, a monumentality, emblematic of both the specific relation between the two human forms and the specific point in time they inhabit. The sculpture, in other words, is a profoundly political work. These politics extend beyond the ongoing fact of the war in Europe. Yes, Moore was a former soldier and a founding member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. His training as an artist was also directly financially enabled by his own service in the First World War, after which an ex-serviceman’s grant enabled him to train at Leeds School of Art, where he began to sculpt in earnest. Yet he was also a lifelong socialist and, in the United Kingdom, one combined legacy of the First and Second World Wars was an increased appetite for, and acceptance of, state intervention in the lives of its citizens.

First recommended in a 1942 report by Liberal economist William Beveridge and his wife, Janet Philip, to address ‘want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness’, the welfare state was something forged in the midst of destruction. It was also something explicitly conceived of as a maternal structure. During its construction, policy makers took up the work, in a broad sense, of psychoanalytic practitioners such as D.W. Winnicott and John Bowlby, who were studying object relations theory, emphasising the importance of an infant’s early caregivers to its later development, as they asked: how could the state care for its citizens? What forms of nurture could it deliver, and how?

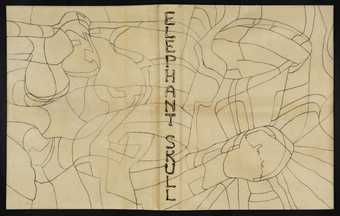

Henry Moore

Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943, cast 1944–5

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved, DACS/www.henry-moore.org 2024. Photo © Tate

Yet fantasies of progress are never quite so simple in practice. The state’s provision of nurture meant it could also withhold it, which it did along prejudiced lines of class and race. The welfare settlement did at least strike a blow against the notion of rugged individual responsibility and self-reliance: it took into account context, and suggested a collective responsibility for each other. Mothers and babies, then, in the mid-1940s, were symbolic of interconnectedness, of newly politicised understandings of need. Moore’s sculptures, in this sense, stand in for both the familiar religious image of the Christ child and the Virgin Mary, and a broader point about relatedness and care (almost, if you will, a kind of Christian socialism).

In the years since 1944, Moore’s renown has increased as the world in which he was sculpting has changed almost beyond recognition. The British welfare state has been the focus of sustained attacks for the last 50 years, with the legacy of Margaret Thatcher’s neoliberal government attacking need (characterised as scrounging), particularly the needs of mothers and children – a task that the programme of austerity that defined the 2010s continues to fulfil well into the 2020s.

In that time, too, the Northampton Madonna and Child has travelled far, having been lent to prestigious international exhibitions befitting the titanic reputation of its creator. Yet Moore’s approach values work that remains in situ, existing in its own surroundings as part of normal daily life among local people. This came sharply into focus during the opening ravages of austerity, when Tower Hamlets council tried to sell Draped Seated Woman, 1957–8, despite Moore’s sale of the work for significantly less than its value to what was then London County Council, in order for it to remain in the socially deprived area.

In St Matthew’s Church, then, this Madonna and Child lives within its context. It has become both an object of tactile devotion – the mother’s knees have been worn shiny from decades of touches – and a kind of time capsule: its base is adorned with newspaper clippings that detail the history of both the sculpture and the life of the church itself. It is a work in a place, and the upright posture both suggests and refuses the inclined postures of care. The mother, looking off to the side, resists an easy affective relationship: she is a symbol of what we don’t remember, and what might come to pass. The sculpture produces a feeling of history, of being in time: it requires touch, and we reach towards it.

Three versions of Henry Moore’s Maquette for Madonna and Child were purchased in 1945 and are included in a solo display of the artist’s work at Tate Britain. The full sculpture stands in the north transept near the Lady Chapel in St Matthew’s Church, Northampton.

Helen Charman is a Fellow and College Teaching Officer in English at Clare College, University of Cambridge. Her latest book is Mother State, published by Allen Lane.