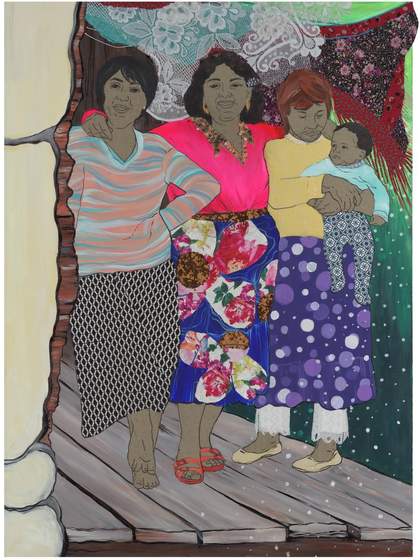

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas

My Mother 2019 (detail)

© Małgorzata Mirga-Tas. Photo © Tate

Bigotries inevitably emerge in the display of Romani art by Western institutions. With representations ranging from curious oddity to flamboyant spectacle, there has historically been a tone of deviance or departure in the framing of work made by members of Europe’s largest, but still widely persecuted, ethnic minority. With a tone of tender optimism, however, Polish-Romani artist Małgorzata Mirga-Tas’s solo exhibition at Tate St Ives gets around this by gently challenging that presupposing gaze. If a neurosis exists in the dynamic, then the show suggests that this might reside within the very spaces and the traditions these institutions preserve, rather than in the artist’s own cultural heritage.

Using abundant, at times discarded, materials – primarily pieces of fabric – and incorporating elements of embroidery and sculpture, emblem and narrative, and the organic and the synthetic into a single work, Mirga-Tas takes an unsentimental view of everyday life. In many ways I regard this to be a new kind of realism, one that is almost posthuman with its emphasis on animal life and the second life of objects. Of course, this realism has nothing to do with the empiricism associated with that word from the 18th century onwards; in fact, its refusal to disregard the by-products of a sterile modernity might even constitute a challenge to it.

Mirga-Tas is often associated with intricate fabric works that take multiple forms and incorporate tablecloths, clothes and curtains, but most fascinating to me are her works on freestanding screens. A screen is a partition or a dividing line. It is used for privacy in some circumstances, and modesty in others. Historically, the screen provided a shield for the noble-woman in her private quarters, a space in which she would be safe from the gaze of servants. For those living in confined spaces today, the screen can provide a refuge of another kind, creating a space of one’s own among the maelstrom of domestic life.

In most cases, however, the screen is used as a way of preventing others from seeing what we do not want them to see. It is a means of concealing the parts of ourselves that do not match with the image we have worked hard to create. The screen replaces the unwanted and the ugly with something that is decorative and chosen. Is this not, in many ways, the tendency of Western art more broadly?

In disavowing itself from the vernacular and the traditions of smaller communities, the white cube gallery concept has commonly been a site of beautification. In dialogue with this tendency, several three- part folding structures are positioned in the centre of Mirga-Tas’s show, presenting as beautiful artefacts on the one hand and strange, surreal objects on the other, as we are allowed to move around them. By alienating the object in this way, its function of concealment is removed. Nothing is hidden and everything is shown. In Sewn with Threads 2019, the panels contain a melange of fabric that creates parity between the female subject and her animal companions. Though each subject is distinct, it is also humbled by the clash of fabrics, with no one figure able to detract from the other. This one scene, which is repeated three times on separate panes, shows the female subject surrounded by a changing array of animals. While they shift and change, she remains constant. Rather than enjoying dominion over the creatures, as seen in early depictions of Adam and Eve through to the noble steeds of George Stubbs, for instance, the subject here has a role of support, humility and deep reverence.

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas

Sewn with Threads 2019

© Małgorzata Mirga-Tas. Photo © Tate

In My Mother 2019, another work made on a folding screen, three panes show a continuous scene of domestic life, incorporating hens made from a paisley fabric and a vibrant portrayal of a plastic chair. The central figure is again recessive, dull compared with the bright colours that surround her. This suggests that Mother, while being an embodied ideal in one sense – and usually celebrated as such with a certain prominence, much like a Madonna figure – is also not reducible to her physical being: she is a world of associated memories and comforts. Mirga-Tas’s mother is both the figure and the entire scene.

Screens are a tangible and externalised form of negation that, in this context at least, force us to question the forms of negation that occur in our own judgements about the authority of the Western canon. Mirga-Tas uses a form that has been historically decorative and distracting to showcase scenes from her own domestic life – a life that up until recently has been excluded from, or placed behind the screen of, the gallery’s respectable and aesthetic veneer.

Mirga-Tas has spoken about the importance of being exhibited in a gallery, but for a group that is still not granted basic rights and protections in many European countries, and is still, in the 21st century, subject to routine clearances and pogroms, it is not a straightforward occurrence. Cultural representation can be seen as a form of recognition, but, as Mirga-Tas’s show urgently reminds us, that recognition must not be conditional on participants accepting the basis of their oppression, in which art has often played no small part.

Audiences who live in societies that still actively vilify and persecute Romani people must therefore be open to critical interpretations that aren’t always easy to digest but, in doing so, can find the great revelation and pleasure that comes with spending time in a world created by someone of Mirga-Tas’s great skill.

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, at Tate St Ives, until 5 January 2025.

Nathalie Olah is a writer and editor. Her latest book is Bad Taste, published by Dialogue Books.

Supported by The Małgorzata Mirga-Tas Exhibition Supporters Circle and Tate Members. Organised by Tate St Ives in collaboration with the Whitworth. Curated by Anne Barlow, Director. With thanks to Helen Bent, Louise Connell, Giles Jackson, and Tate’s conservation, design and technical teams.