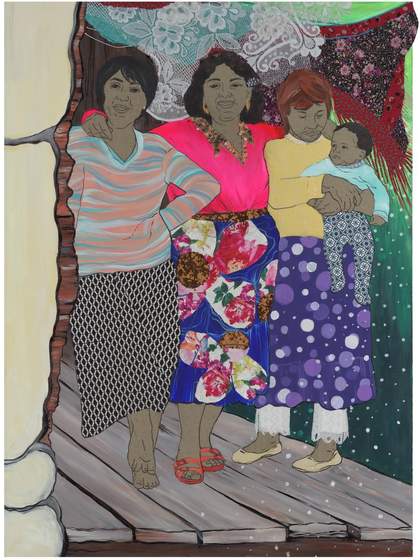

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, Trzy Gracje / The Three Graces, 2021. Presented to Tate by the artist in 2022.

Photo: Marek Gardulski. © Małgorzata Mirga-Tas

I had prepared a list of questions for Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, but when Gosia – as she is known to her family and friends – appears on the screen, there are more important matters at hand. We smile, greet each other loudly, ask after one another’s families. There is work to be done, but our elders would be pleased that we have gotten our priorities right. These are not pleasantries, but rather an acknowledgement of our vital connections. Without them, there would be no art.

The WiFi signal is fragile, which gives our conversation a precarious feeling: the communications are delicate and precious. After a spell living and working in Berlin, Mirga-Tas is back in Czarna Góra, ‘Black Mountain’, a village in the Polish Tatra Mountains where she grew up. She is relaxed and full of energy, in spite – or perhaps, because – of the fact that her house is full of guests. I ask what she has planned for her forthcoming exhibition at Tate St Ives, a space which has a historical connection to sculpture. She’ll be showing textile pieces, including new work commissioned for the show. Tantalisingly, she mentions ambitious scale – ‘a really long and high work, four and a half by three metres’ – and the artistic revivification of Romani women from different countries whose likenesses have been stored away in vaults of documents and art. ‘I want to sew three women,’ she says. ‘I find them in historical images, like drawings from Spain, and from Italy.’ It’s clear she feels a deep connection, across spans of time and geography, with these people: that ‘finding them’ is about more than research.

It is Mirga-Tas’s figurative work using textiles for which she is now renowned, particularly in the wake of Re-enchanting the World, her epic, fresco-like creation for the Polish Pavilion at the 2022 Venice Biennale. She explains how, following her training in sculpture, she has continued to think sculpturally. ‘I am always building,’ she says. ‘Building the levels, the background. But yes, I miss doing something with different materials, not only one.’ That ‘one’ material is cloth: the raw material of the portraits recently showcased in her solo exhibition at London’s Frith Street Gallery, her wide friezes reminiscent of medieval tapestries.

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas in her studio in Szaflary, Poland, July 2024

Photo © Magda Kowalczyk

In Mirga-Tas’s hands, these fabrics seem to acquire the endless potential that paints and inks possess for other creators. But there is much more to these works than their colourful and intricate beauty. Here, cloth is often synonymous with its sister-word: clothes. The portraits are frequently made from the garments of those depicted in them, creating intimate physical links with the subjects that are rarely present in art. ‘When we talk with children about clothes, and which family they are coming from, they are full of emotion. You feel the energy of this his- tory,’ she says.

The grand-scale pieces pose as direct challenges to historical depictions of the Roma. When delving into these materials – from early modern engravings to 20th-century documentary photography – Mirga-Tas is often shocked, particularly by the labelling and titling of the items. ‘These things are somewhere in storage, in some museum, in the archives, and somebody took these images from the Roma community, but without any name: only saying “Gypsy”, you know? They never say, “the woman with child”, “the beautiful girl”. They always put: “Gypsy with child”, “Gypsy with cart”. Why are we not “the beautiful woman?”’

Certain finds have surprised and moved Mirga-Tas to make new, large works. She describes the images she has discovered of Roma people who were living in caves. Searching for the word in English, she conjures a question of great beauty: ‘What is it... when you live deep in the huge stone?’ Caves have often provided shelter to the harried – outcasts, nomads, political exiles, fugitive kings, and Romani people – and as she describes these places, Mirga-Tas gestures with her hands as though feeling her way into the depths, the textures, of both caves and history. She is thinking three-dimensionally again. ‘I want to go back and do something with the texture and paper sculpture, but also wax sculpture. With humans, and with caravans, and, of course, with bears.’

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas

Untitled (After Gentile da Fabriano) 2023

© Małgorzata Mirga-Tas. Collection of Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi. Photo: Marek Gardulski

People and caravans might be expected subjects for a Romani artist, but what of bears, those other sometime cave-dwellers? ‘The topic of the mountain bears is very important for me. The family of bears, the mother with smaller babies, you need to give them space. When we wanted to go to the forest with our boys, a local firefighter told us: “Don’t go there, it’s dangerous now.” They protect them. They talk with tourists, and say: “Stop, you cannot pressure the bears, they are dangerous, but also they are afraid of humans.”’

I ask Mirga-Tas whether she sees a parallel with the way Romani people are often perceived as dangerous, when, in reality, their fear of outside society is more prevalent than aggression towards it. But what draws her to bears is predominantly the history of their use by Romani people as trained animals. They prompt Mirga-Tas to reflect on the complexity of old cultures, their perception, and their moral assessment by others. ‘I saw a movie about Roma people from Bulgaria, and a man who works with bears,’ she says. ‘He travels with them by train. And it’s like I have two different feelings? First, I’m thinking: “Oh, it’s so bad that he does this, that he takes this bear into the city.” But I’m also impressed by this Roma man who did this, that he has the power to train a bear. They grew up close to the forest. They want to protect the caravan around because they’re living in the forest, they need somebody – a bear – to protect them.’ It encapsulates the dilemma that Romani people face when it comes to addressing the aspects of our culture that cause consternation among non-Roma: ‘We can say that we don’t do this anymore, but it’s part of our history,’ she says. Of course, for many Romani people, bear training is not part of their culture. ‘But for people who live in the mountains, like my group, and in Slovakia, Czechia and Bulgaria, for us, it’s normal: if you find a bear, you can protect them; you can also train them.’

We discuss the fact that the different cultures of the various Romani ‘sub-groups’ are often as unfamiliar to other Roma as they are to ‘outsiders’. Mirga-Tas mentions the fact that some are uncomfortable with subdividing the Roma into ‘groups’. These include many of the Sinti – a large Romani group historically linked to Germany and the surrounding regions – with whom she has worked in Italy. ‘One man asked me, “Why are you always talking about the groups? We are Sinti, you are Sinti.” And he thinks that I’m also Sinti, and I said: “No, I am not Sinti”. I want to explain that I’m from the Bergitka Roma, I’m from the mountain Roma, from Poland’. And he asked me, “But what’s that?” He doesn’t know about this group. He asked me: “What does that mean, to be Roma, for you? Are you different or are we different?”’

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas

Family 2022

© Małgorzata Mirga-Tas. Courtesy of the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw and Karma International, Zurich. Photo: Marek Gardulski

What Mirga-Tas finds fascinating is that, despite differences in habits or cultural practice, Romani people have often been portrayed by non-Roma as essentially similar: as though we possess a consistent, readily identifiable, transnational culture. ‘When I reappropriate works from history, in order to change the view and open the topic, I’m shocked by how they have shown us for many centuries. We look the same in Italy as in Russia or Hungary, or in Spain or England. But I know that these are different groups that look different. It’s strange, because you see the different places in Europe, different places in the world, but the representation and the drawings look like the same place.’

I mention the powerful feelings of family, and of individual characters, that emanate from many of Mirga-Tas’s works, and ask what she thinks of the constant interpretation of her art as ‘Roma art’. ‘I think about them as contemporary art,’ she says. ‘I finished the academy. I know that people try to sometimes say this is “Roma style”, but it’s not true. People say, “Ah, you like the colourful textiles, because you are Gypsy or Roma, or you are Cygan, Cygani.” It’s not true.’

Cygan and ‘Gypsy’ have different etymologies. The former, likely derived from the Byzantine Greek word for ‘untouchable’, might be seen as having a more sinister root than the latter, which is a contraction of ‘Egyptian’ and therefore, at least originally, a misattribution of heritage. But what both words have in common is that they do not derive from the Romani language. The use of such exonyms is a subject of active debate, including in the arts, and there are geographical and social intricacies involved, but many Roma would prefer to consign them to his- tory. ‘I want to change this for my children,’ says Mirga-Tas. ‘To not call them Cygan anymore, because in Poland a Cygan is something negative.’

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas

Out of Egypt 2021

© Małgorzata Mirga-Tas. Courtesy of the artist, Frith Street Gallery, London, Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw and Karma International, Zurich. Photo: Marek Gardulski

Mirga-Tas describes a comment that prominent Roma are used to encountering on social media, in which the commenter tells the Roma person that they do not understand the truth about themselves: for instance, that they are calling themselves the wrong ethnic name. ‘They say, “No, you are not Roma, I think you are Gypsy,” So one day, I decided to not read this anymore. The bigger society always think that they can decide about the minority.’

Often, she says, it is the teachers who need to be told. ‘My grandparents, they realised what is important for their future, for the Roma people, is to be stronger and more educated, and to change the perspective about us. The old generation, they still talk about that, that we need to be strong and to not be afraid to say no. I see now children are always afraid to say, “We don’t like that.”’ But in family life, as well as art, she resists the entrenched tendency to respond to fear with silence. ‘My boys have parents who tell them, “In school, if someone says something about Roma, you must react.”’ With her stunning recent work, Mirga-Tas does not just tell: she shows.

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, Tate St Ives, 19 October 2024 – 5 January 2025.

Damian Le Bas Jr is a writer. His first book, The Stopping Places:

A Journey Through Gypsy Britain, won the Somerset Maugham Award and a Jerwood Award for non-fiction.

Supported by the Małgorzata Mirga-Tas Exhibition Supporters Circle and Tate Members. Curated by Anne Barlow, Director. With thanks to Helen Bent, Louise Connell, Giles Jackson, and Tate’s conservation, design and technical teams.