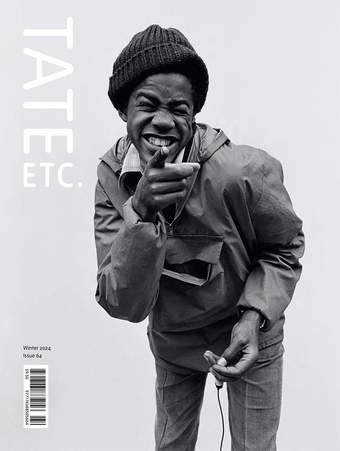

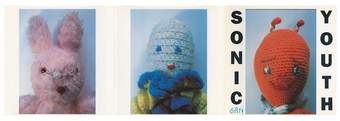

CD inserts from Sonic Youth’s 1992 album Dirty featuring details of Mike Kelley’s Ahh... Youth! 1991

© 1992 The David Geffen Company

STUFFED

I first encountered Mike Kelley via the no wave-turned-noise rock band Sonic Youth. The orange face of an old stuffed toy, part of a larger photographic work by Kelley, constitutes the cover of their 1992 studio album Dirty. Later I discovered that this was just one of Kelley’s forays into art rock. His bands included the Poetics, with fellow CalArts (California Institute of the Arts) students Tony Oursler and Donald Krieger, and Destroy All Monsters, formed with Cary Loren, Niagara and Jim Shaw.

Inside the Dirty CD booklet was an array of even more dejected-looking toys, and, on the back, a vampiric young man in a tightly buttoned-up shirt. I assumed that this was the band’s guitarist, Thurston Moore, partaking in some form of Ted Bundy cosplay. Likewise, the first time I saw reproductions of artworks by Raymond Pettibon and Gerhard Richter on other Sonic Youth albums, I regarded them as ironic-comic and ironic-spiritual japes, rather than recognising them as the ‘borrowed’ works by famous artists.

I was, after all, only 15 then. Dirty had come to me through my big brother a few years after its release and at a point in my life when I had decided that I was definitely not mainstream. I had been keen to establish this fact by emulating the older and therefore automatically more sophisticated aesthetics of floppy-haired Generation X-ers. Nevertheless, the adolescent – but at the same time, knowing – pain embodied in Kelley’s stuffed toy ‘portrait’ seared itself onto my retina.

Mike Kelley

Nostalgic Depiction of the Innocence of Childhood 1990

© Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts.All Rights Reserved / VAGA at ARS, NY / DACS, London

FOUL PERFECTION

During my first term at art school, I was surprised to see this work again – now as Ahh... Youth! 1991 – forming part of an Art History slide show and framed as a reaction to 1970s minimalism. I learned Kelley’s name and that this was one of several stuffed toy works by him, many of which were even more extreme (Yes!) but still realised in the language of juvenilia as critique (Yes! Yes! Yes!). As we say now, I felt seen.

Take, for example, Nostalgic Depiction of the Innocence of Childhood 1990. It presents us with a naked man and woman ‘playing’. The man rubs a stuffed toy across his bottom, which is smeared with a dark, ambiguous substance. Behind him, the woman straddles a large toy rabbit, her vulva pressed to its mouth. The scene is ridiculous yet photographed to ape the ‘serious’ black and white performance art stills of previous decades.

The lecturer in charge of these slides wore tight jeans and cowboy boots, and repeatedly used the word ‘transgression’. Which was one way of putting it. ‘Scatology abounds in caricature, and in other forms of satire’ – a line from Kelley’s essay ‘Foul Perfection: Thoughts on Caricature’ – is another.

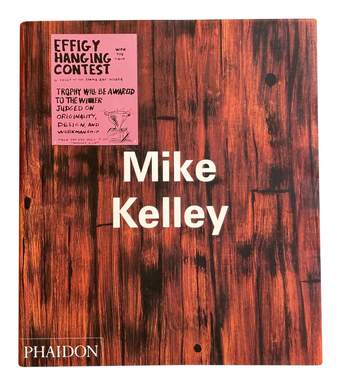

Cover of Mike Kelley (1999) from the Phaidon Contemporary Artists series

FLAPS

Flush with my crush on Kelley (if not cash), I sunk a chunk of my student loan on my first-ever monograph. Back in the early noughties, bookshop tables groaned with the weight of Phaidon’s Contemporary Artists. Measuring 25 × 29 cm (not quite square), the white paperback was enhanced by a thick, matte dust jacket printed with a picture of the artist’s work that wrapped around the entire thing, mimicking French flaps. The series had obviously been designed to sit midway between coffee table ‘literature’ and an accessible version of critical theory.

Having said goodbye (at least temporarily) to bourgeois cultural conceits such as museum postcards – I was now a teenager only as a style – I dived straight in. The first section of the book comprised of an interview with a German critic, whose questions to Kelley included ‘Where do you get this impulse to challenge the dominant understanding of how art should function?’

Like, duh!

Obviously, I took her nationality into account (or adhered to the adage that German humour is no laughing matter), but still the message was clear: not only should Kelley’s brand of lo-fi adolescent humour be regarded as serious art, but serious art that spoke about the ‘lie of the anonymous producer’ (here illustrated with several of his birdhouse pieces, the building of which constituted a typical ‘masculine’ pastime where Kelley grew up. Keen to subvert this suburban craft aesthetic – and the gender norms it reinforces – Kelley’s birdhouses are realised in styles such as Catholic and Gothic. They are poorly made and ‘LOL’ funny). ‘I began to realise that I had to work overtly with my personal life as a kind of fiction,’ said Kelley in (partial) response to this po-faced probing.

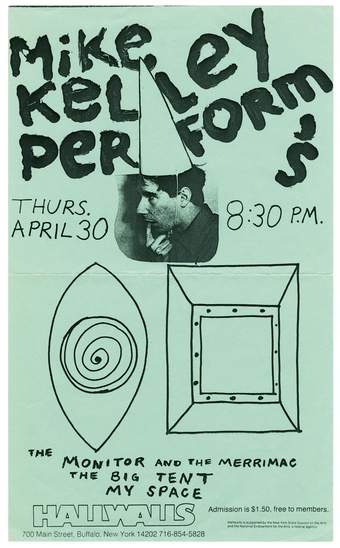

Poster for performance at Hallwalls Contemporary Arts Center on 30 April 1981

© Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts.All rights reserved / VAGA at ARS, NY / DACS, London

ROCK & ROLL

The more I learned about Kelley, the more confidence I gained in my own tastes – that is to say, regressions – and my ‘right’ to insert them wherever I saw fit. When writing Arriviste (2007), my first ‘art novel’ (think small press, ‘selective’ audience, and anything else that befits being written in the RCA Sculpture Studio), I was eager to pay homage to my experience of him. Consequently, I wanted the book to reflect how I was just as angered by those who didn’t ‘get’ Kelley as I was by those who tried to claim him as their own. This took the form of a party scene where I described a group of young old Etonians clad in sportwear plus a curator-DJ who played Destroy All Monsters so as to imbue the occasion with that oh-so-desirable ‘Eighties West Coast’ vibe.

Three years after Arriviste was published, the then-exhibitions manager of a London studio space – also a privately educated individual with a penchant for ‘streetwear’ – commissioned a Destroy All Monsters exhibition called Hungry for Death. The private view was so filled with art students and very rich people dressed as art students that for a minute I wondered if this was a situation that I had somehow unwittingly invented.

I was an early millennial, born on the Gen X cusp. Whereas if Kelley was alive today, he would be called a Boomer. Indeed, it was through my writing about Kelley that I got to know some of his contemporaries, most of whom are now retired. The author and musician Jack Skelley, for instance, sent me pictures of the posters and flyers that Kelley designed for a poetry night in 1980s California, and which, like those featured in Tate’s show, have been full of nostalgia for this previous decade, for many decades now. At the same time, though, Kelley was, and remains, a voice of my generation, even when that generation were, and still are, strangers to one another.

Impromptu memorial for Mike Kelley in Highland Park, Los Angles, 2012. The memorial took inspiration from Kelley’s 1987 artwork More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid, an assemblage of handmade dolls and blankets that Kelley found in thrift stores

Photo: Jennie Warren. Courtesy of Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts

ROT

Sixteen years on, Kelley (re-)appears in my latest book, an ‘anti-memoir’ entitled The Lives of the Artists (aka Not Much in My Life Has Changed Since Then). The work tries to determine what success means to a creative individual, as well as what defines a person as creative, as successful, and whether the twain can meet.

While writing it, I kept coming back to an interview with Gerry Fialka, in which Kelley states how art was only his ‘chosen profession [in that] you chose to be a failure.’ Yet failure doesn’t only mean a lack of recognisable accomplishments, it also means not doing what society expects (‘his failure to comply with the basic rules’ for example). I wanted to be like Kelley precisely because he had failed to be (in a shiny, capitalist, people-pleasing way) good. And yet the thought that he had also failed to be happy broke my obsessive, forever-teenage heart.

In The Lives of the Artists I describe how, on the day that Kelley killed himself, I was working the late shift in the Tate Modern bookshop, which also sold posters of his sculptures. When I heard the news, I felt as though someone had punched me in the stomach, which, bearing in mind that I’d never actually met Mike Kelley, was an embarrassing feeling. Yet it was also a real one.

Afterwards, I read that mourners in LA had left stuffed toys and candles in a disused driveway next to Kelley’s studio. The result was as dirty as anything the artist himself would have done. R.I.P. Mike Kelley: the art world’s most inspiring failure.

Mike Kelley: Ghost and Spirit, Tate Modern, until 9 March 2025.

Susan Finlay is an artist and writer. Her most recent book is The Lives of the Artists, published by JOAN.

Supported by The Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts, The Mike Kelley Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council and Tate Patrons. Organised by Tate Modern in collaboration with Bourse de Commerce, Paris, K21, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Dusseldorf and Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Curated by Catherine Wood, Director of Programme, Fiontán Moran, Curator, International Art, Tate Modern, and Beatriz Garcia-Velasco, Assistant Curator, International Art, Tate Modern.