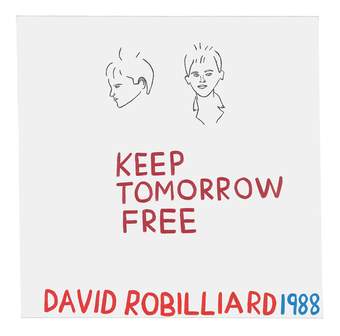

David Robilliard

Keep Tomorrow Free 1988

© Estate of David Robilliard / DACS 2024

The artist and poet David Robilliard’s (1952–1988) maverick paintings seem to send up the authority of painting itself. His performatively naive approach to gesture – like a neat child practising his handwriting – and inclusion of frank textual phrases don’t seem like the considered motifs you might expect to see on a canvas. There’s something enticing yet reluctant about his complex works, as if they don’t want to be paintings at all. But there is a unique magic about his audacious simplicity.

Robilliard moved to London from Guernsey in 1975. In the 1980s, the country’s queer communities were beleaguered by Section 28, a clause introduced by Margaret Thatcher’s government to prohibit the ‘promotion’ of homosexuality by local authorities, and the onset of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, which would claim Robilliard’s life in 1988. Figures such as artist Leigh Bowery, soon to be the subject of a long-awaited Tate Modern survey, and club empresarios Philip Sallon and Steve Strange created nocturnal realms that allowed like-minded denizens of fashion and art to celebrate and adorn themselves, despite the agony of the era.

It wouldn’t be accurate to situate Robilliard squarely in this decadent nightlife frame. He seemed to have more in common with his predecessors – writers in the vein of Joe Orton and artists such as Jean Cocteau – than his immediate contemporaries, demonstrating a more observational and introspective approach. However, he certainly frequented popular nightlife haunts with his boyfriend, Andrew Heard, including Rusty Egan and Strange’s Blitz club night in Covent Garden. At art events and pubs, such as The Bell, he would have encountered many of the queer artists we now associate with the period, including Derek Jarman and Gilbert & George.

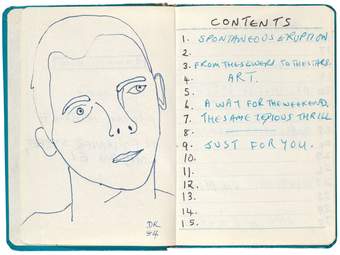

Pages from David Robilliard’s sketchbook, 1984

© Estate of David Robilliard / DACS 2024

Robilliard wasn’t an activist, but he perhaps understood that living as a gay man and transcribing and transforming his sexual and social experiences was itself a political act. In a painting such as Keep Tomorrow Free 1988, resplendent with the words of the title in red capital letters, the artist isolates and amplifies a simple phrase that you might write on the back of a torn cigarette packet for a boyfriend to see upon waking. It becomes loaded with an existential reverence that is undermined through its simple execution. The words ‘keep tomorrow free’ take on a retrospective gravitas considering Robilliard’s premature death.

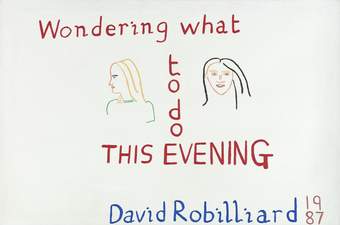

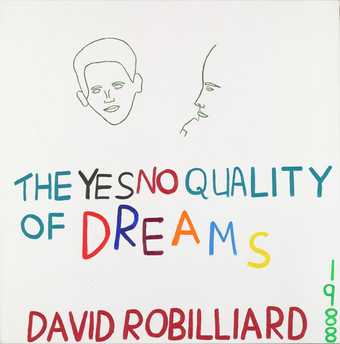

In works from the Tate Collection, including Wondering What To Do This Evening 1987 and That Beat It Quickly Smile 1987, his titular sentiments emerge as bold and childlike, problematising the clarity of language and the gravity of authorial address. A facsimile of his notebooks, published by gallerist Rob Tufnell in 2020, reveals Robilliard’s poetic roots, further illustrating his interest in linguistic brevity and conflicting meanings: many of the phrases that later appeared in his paintings are included here, such as The Yes No Quality of Dreams 1988, which was also the title of a small 2014 survey exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London.

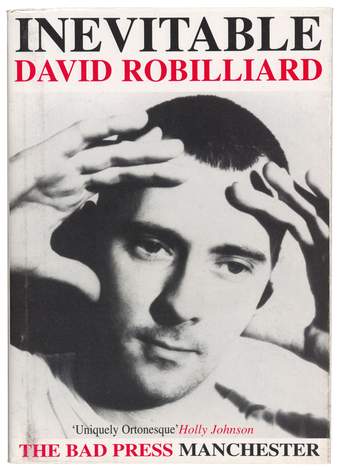

‘Uniquely Ortonesque’ was how singer Holly Johnson of Frankie Goes to Hollywood described Inevitable (1984), Robilliard’s first poetry collection. Those words appear on the cover of its 1996 reissue (The Bad Press, Manchester) below a monochrome portrait of the artist framing his head between two hands, his angelic yet roguish face appearing in the triangle made by his fingers and thumbs. Robilliard was handsome and, judging from this picture, he knew the power in that.

Front cover of Inevitable (1984), David Robilliard’s first poetry collection

© Estate of David Robilliard / DACS 2024

In 1979, artists Gilbert & George met Robilliard, who they would enlist as their assistant. His role entailed street casting models for the duo’s photographic work. They subsequently became strong supporters of his poetry and paintings, encouraging him to combine the two forms.

The famously private artists would candidly write of Robilliard in 1990, two years after his death: ‘Over the nine years of our friendship David came closer to us than any other person. He will live forever in our hearts and minds.’ Despite his short life, his documented wit and intellect left a mark on the city.

Robilliard employed a distinct visual language that might be called a kind of awkward, queer minimalism. Today, I see echoes of his knowing but sometimes obfuscated and deliberately rudimentary approach in the works of young contemporary artists, including Archie Chekatouski and Sam Cottington, who employ everyday objects, such as bicycles, chairs and highlighter pens. In Robilliard’s time, what people nebulously referred to as ‘the gay experience’ was indeed still problematised and largely absent in public life. This led queer artists to find new ways to communicate their most fundamental feelings of love, loneliness and friendship. One of the enduring strengths of Robilliard’s project is its openness to interpretation. New generations of artists continue to resonate with the sensibility of his quivering words today.

That Beat It Quickly Smile was purchased with assistance from Evelyn, Lady Downshire’s Trust Fund in 2011. Items relating to David Robilliard’s work are held in the Tate Archive.

Sean Burns is an artist, editor and writer based in London.