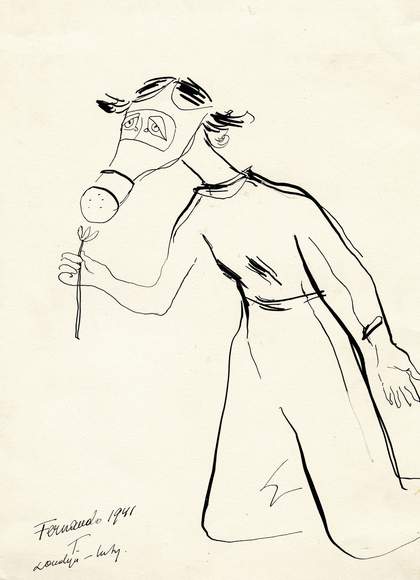

Franciszka Themerson

Fernando 1941

© Estate of Franciszka Themerson and Stefan Themerson

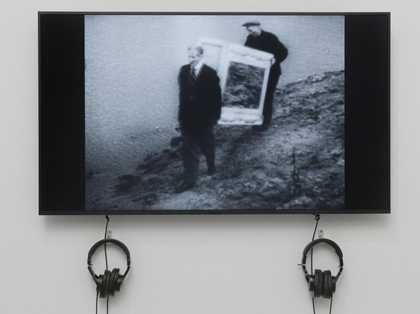

The display presents three stages of Franciszka Themerson’s work. The first consists of two films that belong to an early period of collaboration with her husband, Stefan Themerson, in pre-war Poland: Europa, based on a 1925 futurist poem by Anatol Stern and considered to be the first avant-garde film made in Poland (12 minutes, 1931, originally silent); and The Adventure of a Good Citizen (10 minutes, 1937, with actors and sound).

Both films, in their very different ways, are political. Europa is about social crisis, a tragedy of Europe on the edge of a precipice, about to consume itself. There is a moment of hope when a blade of grass gradually dislodges the surrounding paving stones and grows into a tree. After Europa, lost during the war, was rediscovered in Berlin’s Bundesarchiv in 2019, Lodewijk Muns composed music for it.

The Adventure of a Good Citizen, the Themersons’ fifth film, is about a man who, on overhearing the statement ‘the skies won’t fall if you walk backwards’, decides to do just that. For the public at large, walking backwards is deemed unacceptable. Protesting and carrying placards, they follow the Good Citizen into the woods. Finally, he escapes onto a roof and, while sitting next to a chimney, addresses the audience: ‘You must understand the metaphor, ladies and gentlemen.’ Stefan commented that the film also makes sense if you watch it backwards.

Franciszka Themerson

Nuit de ténèbres 1942

© Estate of Franciszka Themerson and Stefan Themerson

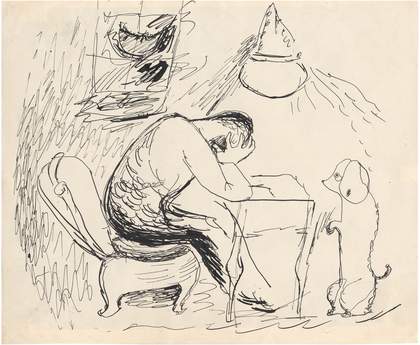

Across two walls, the display presents rarely seen works by Franciszka – her wartime drawings, 1940–2. These were made after her arrival in England in 1940, while she was working for the Polish government in exile as a cartographer and illustrator. It was then that she discovered that Stefan was still alive and in France, confined in a hostel for Polish soldiers in Voiron, and unable to get out of the country.

She called these drawings Unposted Letters, which indeed they were. Sometimes the subject is obvious, occasionally in metaphor, mostly in black and white, with a few drawings in colour. They show uncertainty, pain, despair, but sometimes there is a smattering of hope, as with the image of the dog in front of Stefan’s desk (Franciszka herself), that will escort him out of France.

Of course, these were not the only unposted letters. Many letters were written, but not wanting to communicate further disturbing news, Franciszka kept some of them in a drawer. The complete set of letters, translated into English, was published by Gaberbocchus Press in 2013. Of the drawings in this series, 46 have been shown in London only once before, at the Imperial War Museum in 1996. Now at Tate Britain, some 28 of them are on display on the blue-grey walls as an accompaniment to their story.

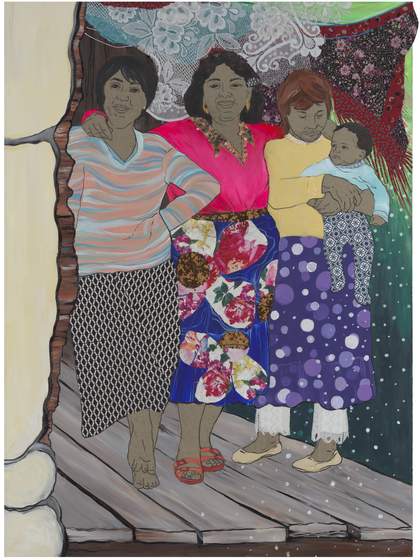

On another wall, there are three of Franciszka’s oil paintings. The earliest one, Two Pious Persons Making their Way to Heaven, one propellered and the other helicoptered, with a little angel below 1951, represents Franciszka’s departure from the pure abstraction of her earlier paintings. Here are the remnants of geometric forms, straight lines and triangles, now combined with human figures on a white background – elements that she returned to throughout various stages of her work. Many of her paintings incorporate a drawn line, combining painting with drawing, and some, like this one, are like a humorous fable.

Franciszka Themerson

Comme la vie est lente et comme l’espérance est violente 1959

© Estate of Franciszka Themerson and Stefan Themerson

In another painting made three years later, there is once more the drawn figure, white textured background and triangles with colour. Now, the light-hearted mood gives way to puzzlement or amazement. Alors on ne sait pas (quoting Raymond Queneau) is the title. Franciszka often used quotations for her titles, most of them from French writers.

In the biggest painting on the wall, made in 1959, the increasingly textured white background of these two early 1950s paintings gives way to a more complex network, with many layers of different tones of grey and lines that combine into a solid texture. There are two main, solid figures filling the space of the canvas. I have always identified the one on the left, with a slight smile, as a female, and the pensive one on the right as a male, joined or divided by a strip of light yellow. They face forward, but, judging by their feet, they appear to be on the way out of the picture; the long arm of the figure on the right is waving. The small third figure – top left and hanging upside down – is Franciszka herself. This is her signature, which appears in many of her works; ‘Am I mad or is the world upside down?’, she asks. In this painting, the face of the signature figure seems disturbed. Yes, of course, the world is upside down and this is Franciszka’s reaction to it.

As for the title, this one is from Apollinaire: Comme la vie est lente et comme l’espérance est violente. But however much we might have liked to know what this or any other painting is about, Franciszka never explained.

Comme la vie est lente et comme l’espérance est violente was purchased with funds provided by the European Collection Circle in 2024 and is included in the display Franciszka Themerson: Walking Backwards at Tate Britain, until 30 March 2025.

Jasia Reichardt is a writer on art. With Nick Wadley, she edited the Themerson Archive Catalogue (2020).