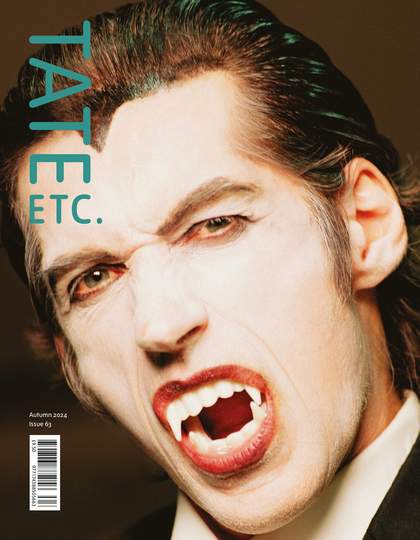

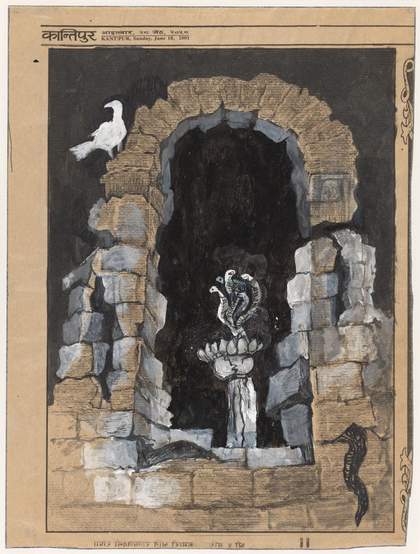

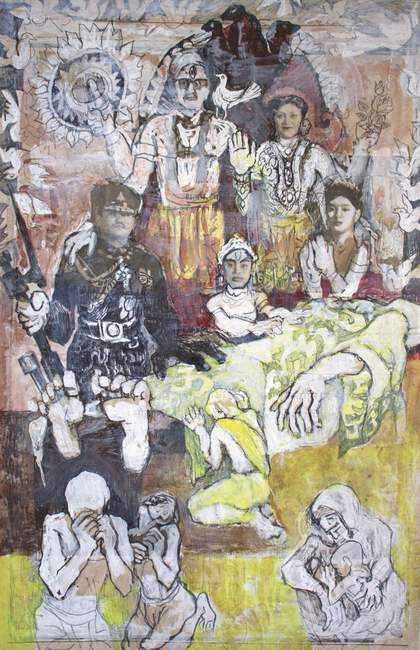

Shashi Bikram Shah

Royal Massacre Series 2001 (details)

© Shashi Bikram Shah. Photo © Tate

Shashi Bikram Shah (born 1940) is a pivotal figure in Nepal’s contemporary art scene, seamlessly bridging traditional and modern elements in a body of work that honours his heritage while showcasing his innovative artistic approach. His Royal Massacre Series recently became the first works from Nepal brought into Tate’s collection. This series comprises 15 double-sided works on newspaper in which the artist responds to the tragic events of June 2001, when nine members of Nepal’s royal family, including King Birendra and Queen Aishwarya, were assassinated. In the days that followed, Shah made use of the newspapers delivered to his home to make the artworks. Since a curfew was in place, these newspapers, featuring both obituaries for the royal family and messages of congratulations for the new king, were one of the few sources of information available to the artist at the time. The massacre was a turning point in the recent history of Nepal, ushering in a period of political turmoil and transformation, and accelerating the country’s shift to republicanism.

BEATRIZ CIFUENTES FELICIANO How did your journey in the world of art begin?

SHASHI BIKRAM SHAH I started my art education at the Durbar High School in Kathmandu. Most students did not opt to study art, and many did not receive support from their families, but at home my mother and siblings drew, made crafts and embroidered, and they encouraged me to pursue this field. I was later awarded a scholarship to the Sir J.J. School of Art in Mumbai. It was there that I finally gained an understanding of art. I acquired a perspective on the fabric of the cosmopolitan city of Mumbai, a city that was referred to as ‘the gateway of India’. The Sir J.J. School of Art was established during the colonial period and its curriculum was influenced by Western art history. While I was studying there in the 1960s, I was introduced to a pedagogy and practice that we didn’t have access to in Nepal. Back home, art was mostly limited to reproductions of landscapes, or religious imagery. My views on art and the world vastly expanded in Mumbai, and my teachers and peers were hugely influential. I was also able to travel around India, which was an important learning experience. My artistic practice is rooted in my South Asian context, and you can see this in the imagery and narratives I reference in my works.

By 1968, I was back in Nepal. There, I joined the Lalit Kala Campus, a public art college, as a teacher and later became the principal. I was also a member of the Nepal Association of Fine Arts and the Royal Nepal Academy. At the same time, I was always making my own art.

All the institutions I worked for were established under the patronage of the monarchy, and I personally feel a sense of debt to King Birendra for my artistic career. I started my career alongside numerous colleagues from Nepal, with many of us completing our degrees in India. In Kathmandu, we had artists who were trained in Dhaka, Mumbai, Baroda, Varanasi, Lucknow, Lahore and Kolkata, all working in close proximity. What we observed, particularly starting in the 1960s, was truly exceptional: Nepal, for the first half of the 20th century, had been closed off from the outside world, but as the country liberalised in the 1950s, you saw new ideas circulating in politics, literature, art, music and film.

BCF Could you tell us about your involvement with the art collective SKIB, and the role it played in shaping contemporary art in Nepal?

SBS When I lived in Mumbai there were many artists, including those from the Progressive Artists’ Group who are now internationally renowned. Some of us Nepali students thought it would be interesting to bring elements of the Mumbai art scene to Kathmandu. This idea would later materialise as SKIB collective, which we established in 1971. There were four of us, including Krishna Manandhar, Indra Pradhan, Batsa Gopal Vaidya and me. The name derived from our initials.

SKIB was based on our collective understanding of art making. We used to fund our own exhibitions and were fortunate to get support from the Nepal Association of Fine Arts, the Young Artists Group, and figures from the literary circle. We were active for around two decades until Indra’s death in 1994. Our exhibitions were held at least once a year in Kathmandu, and we also managed to tour a few works to Pokhara in Nepal and Darjeeling in India. The exhibitions used to attract a lot of visitors – I think we paved a path for collective art practices to later flourish in Nepal.

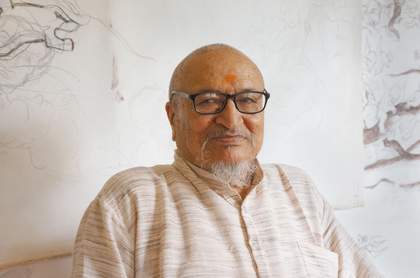

Shashi Bikram Shah in his studio in Lalitpur, 2017

Photo: Priyankar Chand

BCF Your Royal Massacre Series is both powerful and poignant. What was the inspiration behind the series?

SBS The massacre in the Narayanhiti Palace of Nepal was very unsettling. It was shrouded in mystery, and, at first, we were not aware of the extent of what had happened. On the radio and television, they kept repeating that, during a scheduled weapons check, the King and his entire family had died. There was no shortage of conspiracy theories. Later investigations by a high-level committee revealed that the Crown Prince himself had committed the atrocity. When King Birendra and Queen Aishwarya were taken for their last rites, you could witness thousands of people on the streets. This event not only shook Nepal to its core but also caused a sensation globally.

In Royal Massacre Series, the photograph of the royal family repeats itself. This image may be the most reproduced in Nepal’s history – you still see it plastered across public transportation. But the series is not just about one family. I was thinking deeply about the situation across Nepal. In the early 2000s, there was an ongoing conflict in the country and the Maoist insurgency was very active. People were suffering both at the hands of the Maoists and the government. My drawings contextualise the pain that was unfolding.

You can also observe imagery and narratives that draw from Hindu myths and traditions. In one work, I have cut out the portrait of the family and reconfigured it to appear like a devotional poster used in prayer rooms. The monarch in Hinduism is supposed to be a living embodiment of Vishnu. So, there is a constant, direct reference to these traditions and beliefs. You can also observe certain avatars of Vishnu, such as Matsya the fish, Kurma the turtle, and Narasimha the man-lion. These incarnations are said to have protected humans during times of trouble.

In Nepal, I often need to clarify that these aren’t religious works of art. They have a political as well as a surreal dimension to them. In my other works, you see the presence of a horse. Often, this horse is a figure representing Kalki, the avatar of Vishnu that is yet to come. It is said he will arrive on a white horse to save humanity from the Kali Yuga, our current age. Particularly after the 1990s, I started painting horses in many of my compositions. While the horse does not feature in this series, the themes of suffering, fear and chaos are still present.

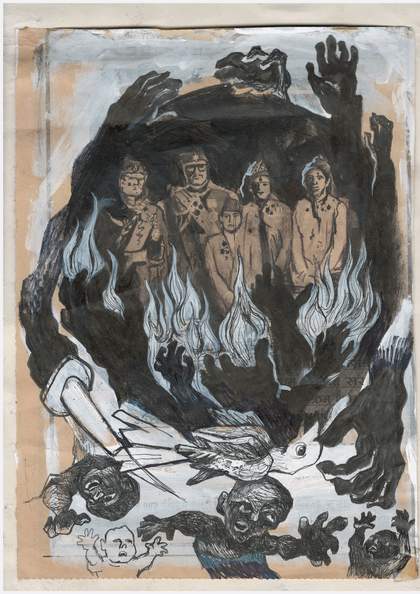

Shashi Bikram Shah

Royal Massacre Series 2001 (details)

© Shashi Bikram Shah. Photo © Tate

BCF Your use of newspaper in Royal Massacre Series is particularly striking. Why did you choose this material, and more broadly, can you tell us about your use of paper and found materials?

SBS When I heard the news of the massacre, it was a moment of shock. I wasn’t capable of painting anything for days; it didn’t seem appropriate. I would pick up the newspapers delivered to my home and the juxtaposition of images was astounding. On one side were condolences for Birendra’s family and on the other, congratulatory messages for Gyanendra, the new king. I decided to use these images as my material, and made drawings and scribblings in a rather extemporaneous manner. These pieces were produced in a very short window of time – I would work for hours on end until late into the night. I think it took around two weeks to finish. I wanted to visualise the emotional and historical weight of such trauma. I think this captured what I was feeling, as well as the state of dismay that was palpable across the nation.

The size of the paper made it easy for me to work from my bed – I only needed my pens, markers, and a few colours. If you visit me today, you’ll see that I don’t have a proper studio. Every nook and cranny of my house, the veranda, the living room – wherever I am at ease – that place becomes my studio.

But I also feel that I had a certain familiarity with paper. My father Chuda Bikram Shah had a government contract to manufacture Nepali lokta paper and he set up a small factory in our house. Back then, we did not have imported paper in Nepal, and lokta paper is a material that remains popular among artists for its durability. My father would collect 19th-century manuscripts from the archives of the government and pulp them to produce recycled paper. I grew up with these manuscripts scattered throughout my house. My sculptures, too, are made using pulped paper, which I recycle from left-over packaging, newspapers and invitations. This practice of working with found materials, and paper in particular, is based on my observations as a child. And while I wasn’t thinking about it explicitly while making Royal Massacre Series, there is a connection between the circulation of paper and statecraft that has always fascinated me.

Shashi Bikram Shah

Royal Massacre Series 2001 (details)

© Shashi Bikram Shah. Photo © Tate

BCF As a prominent figure in contemporary Nepali art, how do you reflect on your role and your art?

SBS My art is informed by contemporary events, and although I have not categorised myself as belonging to any specific art movement – I believe such work is better left to critics and historians – my works do have parallels with modernist movements across the Global South. While Nepal does not have a colonised past like much of South Asia, in the regional postcolonial period there were conversations around national aesthetics and identity. I have also been influenced by impressionism and surrealism, but at the same time my work is grounded in Nepal, and I take inspiration from multiple periods, places and local practices. I also feel that there is a unique imprint of my thoughts, my individuality and my humour in what I make.

BCF Your artworks are now on display at Tate Modern, marking a significant milestone, as these are the first Nepali works in Tate’s collection. How do you feel about this recognition?

SBS I had never imagined that my works would end up at Tate. It’s an honour to be a part of a collection that houses other esteemed South Asian artists such as Bhupen Khakhar, whose paintings I have always admired; Mohan Samant, who was also at the Sir J.J. School of Art; Mrinalini Mukherjee, whose father, Benode Behari, worked in Nepal; and Zarina Hashmi, who trained at Atelier 17 in Paris, alongside my Nepali colleague Urmila Upadhyay Garg.

I believe that the acquisition highlights recent developments in the contemporary art scene of Kathmandu. Platforms such as the Kathmandu Triennale have become important at a regional and global level. In a way, these works were acquired because the Triennale brought them into circulation – they had been sitting in my archives for nearly 20 years. There is a new generation of curators, thinkers and creative practitioners who are critical and truly passionate about the arts, and while this work may be the first from Nepal, I am sure it won’t be the last.

Royal Massacre Series was purchased with funds provided by the South Asia Acquisitions Committee in 2022 and is on display in Media Networks at Tate Modern.

Shashi Bikram Shah talked to Beatriz Cifuentes Feliciano, Assistant Curator, International Art, Tate Modern.