‘Hansel, put out your finger for me to feel how fat you are.’ Arthur Rackham illustration from the English edition of Grimm’s Fairy Tales, published in 1909

Mary Evans Picture Library

The little boy is in big trouble. Eyes owlishly wide with nightmare panic, this wily lad who got lost on his merry way through the forest watches the witch from the cage he’s trapped within. Where are we? Fairy tale country, of course: the English illustrator Arthur Rackham drew this famous scene from Hansel and Gretel in 1909 for a children’s volume of German folk tales collected by the Brothers Grimm. He has the wisdom to show the witch’s blind approach from behind, and thus permitting our brains to overheat with fantasies about how hideous the crone might be: picture her repulsive mug leering at you through the bars.

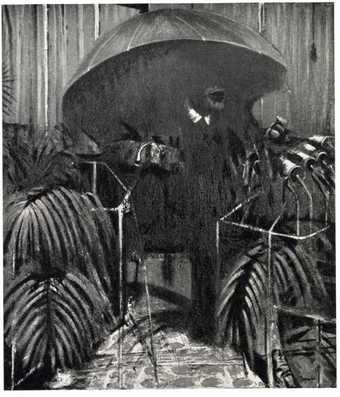

Rackham’s illustration catches a whole bunch of anxieties that cages stimulate in our collective imagination, including claustrophobic dread, fears of being treated like a beast, getting fattened for the pot, or being suddenly condemned to a lifetime in solitary confinement. Cages are for wild things: they suggest zoos and grotesque curiosities seen at freak shows. They aren’t to be inhabited by humans, except in the most abject or outré scenarios. In Tony Scott’s 1982 horror film The Hunger, the rock group Bauhaus croon their goth ode Bela Lugosi’s Dead to an audience of nightclubbing vampires from inside an enormous cage, making it into the arena for after-dark fun. The first prisoners at Guantanamo Bay were notoriously often kept in cages, too.

Such a mixture of dark thrills and fears means the cage is a fascinating vessel for any artist to inhabit, supplying a space for all kinds of psychological troubles to be exorcised. Just a swift montage signals what versatile and perverse experimental purposes the cage has long occupied in art history. The enigmatic American artist Cady Noland captures contemporary alienation via the military-industrial tactic of setting her sculptures and assemblages (pop-up loons from history’s shooting gallery with their eyes blown out; innumerable chilled beer cans stacked to the roof) within cages and wire fences.

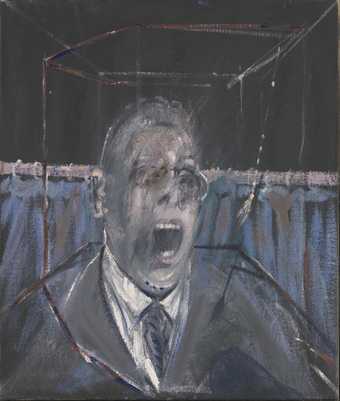

Nobody has found more wicked energy in contemplating the cage than Francis Bacon. The Irish painter’s terrifying interiors are frequently furnished with cages to intensify their torture chamber atmospherics. The outline of a cage looms at the back of the hot purple and orange room created for After Muybridge – Woman Emptying a Bowl of Water and Paralytic Child on All Fours 1965, where warped homunculi, their bodies gory explosions of jelly and bone, perch on top of a railing. Cages provide areas for Bacon to stage his ferocious meditations on human anguish and savagery, but they also assume more distorted forms, shifting like the spaces within a bad dream. The primal coupling glimpsed in Two Figures 1953 occurs in a ghostly enclosure suggestive of a sadist’s bedroom yet wreathed with moonlit grass.

Film still from Tony Scott’s The Hunger 1983, showing Peter Murphy and Bauhaus performing Bela Lugosi’s Dead

MGM/UA / The Kobal Collection

Edwin Landseer, Isaac van Amburgh and his Animals 1839

Royal Collection Trust, © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016

Or consider Bruce Nauman’s early movement studies on film such as Beckett Walk 1967, in which the artist performs vertiginous experiments on his gait within a tight square outlined on the studio floor. The grid, that essential structure depended upon by practitioners as various as Agnes Martin or Bacon’s favourite photographer Eadweard Muybridge to order their inquiries into motion or space, is nothing other than a cage dismantled and laid flat.

Even as genteel a painter as Edwin Landseer created an ominous effect by depicting a man in a cage. His 1839 portrait of the mettlesome American animal trainer Issac A. Van Amburgh shows its circus attraction subject radiant in a suit of Roman armour, sprawled in a sideshow carriage amid a resplendent congregation of lions, tigers and leopards as a baffled crowd watches him through the bars. Being caged routinely means being the object of special but sadistic attention. In Landseer’s painting, a caged man implies a carnivalesque confusion between whatever it means to be civilised or animal.

Detail from the central panel of Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights 1500–5, oil on oak panel

© Museo Nacional del Prado

But longer and more austere confinements can be unexpectedly fruitful, too. The English artist Richard Dadd painted his greatest works under lock and key at Bethlam Hospital in London where he was confined for two decades. A prodigious young draughtsman, Dadd lost his mind in 1842 while journeying up the Nile. Afflicted by what was most likely paranoid schizophrenia, he became convinced he was channelling Osiris, the god of the ancient Egyptian underworld. During his attempted convalescence at the family home in Kent, he murdered his father, certain the old man was the devil in a trickster’s costume. Once incarcerated, he worked on extraordinary paintings such as The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke 1855–64, conjuring make-believe worlds on canvas where they appear as exquisitely coloured as butterfly wings. Crowded with supernatural flash and microscopic detail, Dadd’s works look like curious relations to Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights c1500–5, rambunctiously transforming the Dutch painter’s surveys of creatures up to mischief in hellish carnivals into tableaux capturing life in some green and pleasant wonderland. The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke teems with tiny gnomes and frisky sprites: a cavernous world is created on a Lilliputian scale.

Sometimes Dadd abandoned the enchanted hollows of his dreams to paint weird tableaux that seem to hint obliquely at his psychic troubles. Bacchanalian Scene 1862 shows three crazed satyrs tumbling through an Arcadian forest. The poet Emily Dickinson, the artist’s contemporary and herself no stranger to solitude or confinement, evokes the scene best with her lines mapping land ‘all overgrown with cunning moss/All interspersed with weeds’. Amid the anarchic bracken and sour fruits, everyone looks unwell: the central satyr, androgynous as a New Romantic pin-up, stares with an opiated gaze at somewhere beyond our knowledge. Freaking out, the figure over his shoulder resembles a lunatic abducted from a painting by Bruegel the Elder. In a photograph of Dadd taken in his little room (‘cell’, maybe, is more accurate) the painter looks equally discombobulated. Beard unruly, eyes bright, he looks like a weather-beaten hound crossed with a troubled monk. Brush paused over the surface of Contradiction: Oberon and Titania 1854–8, he stops to consider an unseen guest.

Cells were a chief obsession for the French-American artist Louise Bourgeois. She started making a sequence of creepy sculptural environments under that name in the 1980s and continued until shortly before her death in 2010. Anything by Bourgeois dwells darkly on the concept of home as somewhere horror runs amok, beginning with her early drawings (Femme Maison 1945–7) where women appear as disorientated giantesses with houses for heads, and these works are the most aggressive and alien instalments in her œuvre. In the 1994 BBC documentary No Trespassing, she recalls her father as an ogreish Anglophile who conducted a long affair with his children’s English teacher while she stayed in the family home. For the artist, the discovery of this illicit romantic entanglement was totally shattering. ‘She betrayed me,’ Bourgeois asserts in the film, before making a whip-smart revision to include her father: ‘It was a double betrayal.’ The Red Room (Parents) 1994 is a reckoning with this trauma, setting all visitors within Mother and Father’s bloody chamber. Bourgeois had a hotline to the Freudian unconscious, and this cell is furnished with the kind of jumbled apparatus old-school psychoanalysts crave: a mannequin’s severed red hand lies on the bed, a needle pricking its fingertip – the same item sent Sleeping Beauty into her long slumber – and ‘I love you’ is stitched on the pillow. (Impossible for Bourgeois to hear those words as a young girl and not think they were laced with a dash of poison.) The Red Room is a ghoulish renovation of Freud’s all-important ‘primal scene’ in which the adults making love essential to the old Viennese doctor’s theory find themselves replaced with objects: sublimation is a spooky game.

Louise Bourgeois, Cell XIV (Portrait) 2000, steel, glass, wood, metal and red fabric, 188 x 121.9 x 121.9 cm

With their oubliette vibe, Bourgeois’ cells also evoke other kinky lairs, including the padded rooms found in psychiatric hospitals and the desolate rooms seen in stop-motion films by the Brothers Quay where dolls perform sinister ballets. Denuded of all but the uncanniest symbolic debris, they’re seemingly the products of rummages through a haunted storage space (memory, under another name) that suggest scenes from a frightened child’s dreamscape.

When she was 16, having long endured homophobic rage from local dolts, the American video artist Sadie Benning ditched high school and spent three weeks in self-imposed solitary confinement, making her film Living Inside 1989, a confessional self-portrait shot entirely within her bedroom in suburban Milwaukee. With the picture ghostly thanks to the lo-fi Fisher-Price Pixelvision she used, the film is at once an eerie account of teenage angst – all the psychological dejection that was goofily summed up later by the Smashing Pumpkins’s chorus ‘Despite all my rage, / I’m still just a rat in a cage!’ – and beyond prescient in its rough-and-ready technique. Benning makes all social media’s claims about providing newfangled notions of intimacy or the most accurate seismograph for everyday chaos which arrived almost two decades after her five-minute film look fatally passé. A report on her fragile state of mind, Living Inside is punctuated by bursts of panicky static, the videotape’s degeneration with every jump cut signalling that its owner is on the edge of a major breakdown. With her strung-out gaze occupying the whole frame, she constantly updates her anxieties: ‘My dog is old and so is grandma… I should be at school, somehow I can’t get myself to go.’

Stills from Sadie Benning’s Living Inside 1989, black-and-white pixelvision video with sound

© Sadie Benning, courtesy Video Data Bank, Chicago

Escaping the cage might sound like a wise ambition or respectable dream, but it’s also a rather obvious response to such an intoxicating space. When an artist climbs into the cage, anything goes: you visit more extreme regions of consciousness; horrors from the imagination come to life or hungry beasts strut out of the shadows. Not that anything appearing in a cage can’t be beautiful – Joseph Cornell trapped all kinds of shabby wonders in his boxes; Franz Kafka wrote in his notebooks of ‘a cage which goes in search of a bird’ – but bewilderment and fear often lie in wait for any visitor. Who knows what you might discover? When you come near the cage, beware.