Mary Delany

Lilium Canadense 1779

© The Trustees of the British Museum

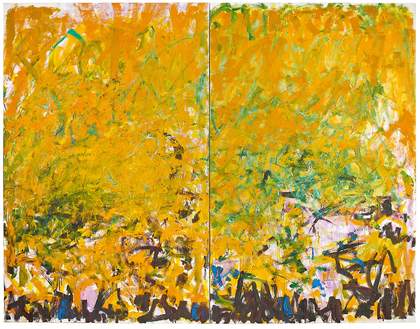

Something strange is happening in the Flora Delanica, a series of 985 flower specimens compiled by the gardener and artist Mary Delany (1700–88) in the late 18th century. At first glance they appear to settle neatly in the genre of the hortus siccus – a herbarium of dried plants – but on closer look, something is off. Where specimens fade and wrinkle, losing pigmentation and moisture to become another, insectile thing entirely, the flowers in the Flora Delanica bloom with the uncanny vibrancy of the just plucked. Their colours are preternaturally vivid yet freakishly uniform in texture. Each flower seems a rearrangement of the same gleaming consistency, too jewel-like to be specimens – even living ones. Two-dimensional and rootless, Delany’s flowers glow from their pages with the self-satisfaction of the living dead.

This trompe l’oeil effect, finicky and a little camp, was innovated by Delany at the age of 74. Delany had previously been a skilled gardener and painter, but when her eyesight began to fail, she turned to scissors and coloured tissue paper to create what she called ‘paper mosaiks’, inventing a form of collage in the process. Writing after her death, the poet Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles) described Delany’s process as one of scientific accuracy, ‘less liable to fallacy than drawings’, since each mosaik was made true to size, always from observation, and every gradation of hue in petal and leaf was cut from a different colour of paper, painstakingly layered and arranged to create an impression of depth. Her choice of mounting on black was innovative too, at a time when flowers set against creamy backgrounds was the fashion in botanical illustration, later epitomised by the sensual, magisterial watercolours of Pierre-Joseph Redouté.

Delany, whose life spanned the long 18th century, had more business with flowers than she did with men, and her lifelong botanical vocation can be seen as a proxy for pressing against the confines of her gender. She was widowed twice, first at 25 by a parliamentarian pushing 70, and then again in her late 60s. In between these marriages she enjoyed two decades of singlehood, and deplored in letters the ‘irksome prison’ of matrimony. She preferred female friendship, ‘the true zest of pleasure’, and fantasised about taking her revenge on certain members of the male sex: ‘Would it were so, that I went ravaging and slaying all odious men ...’. It was her friendships with women, particularly the wealthy Duchess of Portland, that furnished her with the time and resources to pursue her botanical interests. After being widowed a second time, she cohabited with the Duchess for 17 years on her Bulstrode estate in Buckinghamshire, and it was there that Delany met prominent botanists and plant collectors such as Joseph Banks, and encountered the new intellectual vogue for Carl Linnaeus’s system of plant classification.

Much has been written about the heteronormativity Linnaeus imposed on plants; discovering their sex life to be variously polyamorous, homosexual or hermaphroditic didn’t sit well with the Swedish son of a pastor, who believed sex was only appropriate between a husband and wife, and with procreation in mind. And so, the queer and diffuse sexuality of plants was straightened into a rigid binary – Linnaeus dubbed the stamen and pistil as ‘husband’ and ‘wife’, and allocated their genitals accordingly. At the same time, botanical illustration was considered a gentle and edifying pastime for women, seen as closer to the decorative arts and therefore distanced from the masculine genres of historical and religious painting. In this context, is there any room to read Delany’s images against the grain of gender conformity?

Mary Delany

Rubus Odoratus 1772–82

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Mary Delany

Crinum Asiaticum 1780

© The Trustees of the British Museum

It seems odd, or maybe perfectly scripted, that the plant life so eroticised by Linnaeus’s system was also seen as the most harmless object for women’s artistic pursuit. Perhaps the perceived demureness of women’s flower painting was vastly overrated by men, who thought themselves the only ones excited by moist pink petals and a firm, sizeable spadix. Writing on Delany’s paper mosaiks, the poet and academic Lisa L. Moore has suggested that they demon- strate a heightened erotic sensibility, comparing a ‘chastely closed’ magnolia bud depicted by Redouté with Delany’s splayed-open view, ‘seeming almost to pull the petals back to reveal the heavy, creamy yellow pistil in the centre.’ Moore sees sapphic imagery in such aesthetic choices – recall that in Linnaeus’s met- aphor the pistil is the ‘wife’ – and in the stuffy gender essentialism of late 18th-century botany, it’s certainly satisfying to imagine Delany taking pleasure in such imagery, queering female desire in plain sight of its most normative enforcers.

We can’t know what Delany saw when she arranged each flower as a model for her mosaiks, but we do know she was clearly compelled – as anyone creating a series numbering nearly a thousand would have to be. The completist mindset of this fixation is redolent of another 18th-century botanophile, the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Delany and Rousseau moved in similar circles – Delany’s brother Bernard Granville was Rousseau’s neighbour at Wootton, during the philosopher’s stint in England – but Delany refused to meet him on the grounds that his ideas were too dangerous. Yet viewed through a botanical lens, their biographies seem sympathetic to one another, both using botany as a solace and a means to cope with the strictures imposed on their lives: Delany’s disdain for marriage and preference to cohabit with women, and Rousseau’s tormented exiles in England and Switzerland following the publication of books deemed subversive and dangerous by the French authorities.

Rousseau fell in love with botany in the early 1760s while lying low on the Swiss lake island of St Pierre. The fifth walk of his Reveries of the Solitary Walker, published in 1782, six years before Delany’s death, details his time there: ‘I could have written [a book] about every grass in the meadows, every moss in the woods, every lichen covering the rocks – and I did not want to leave even one blade of grass or atom of vegetation without a full and detailed description.’ Where Rousseau – to our knowledge – failed to produce such an anthology, Delany succeeded in making the completist fantasy a reality. Volume definitely plays a part in what’s so compelling about her paper mosaiks; while they can be contemplated individually, there is something dazzling about their sheer number. It makes them improbable, fantastical, less a part of nature than a projection of obsessive, cumulative desire: a thousand queer gardens.

Rubus Odoratus and Crinum Asiaticum are included in the exhibition Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520–1920, The Linbury Galleries at Tate Britain, until 13 October.

Daisy Lafarge is a writer who lives in Glasgow. Her latest book is Lovebug, published by Peninsula Press.

In partnership with Lockton. Also supported by Julia and Hans Rausing and The Christian Levett Collection with additional support from the Now You See Us Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council, Tate Patrons and Tate Members. Curated by Tabitha Barber, Curator of British Art 1500–1750, with Tim Batchelor, Assistant Curator of British Art 1550–1750.