Florence Claxton

Woman’s Work: A Medley 1861

Private collection c/o Martin Beisly Fine Art, London. Photo courtesy Martin Beisly Fine Art, London

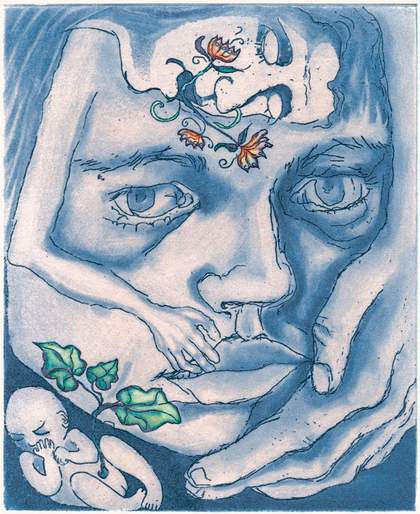

Levina Teerlinc’s Fictional Afterlives by Catherine Padmore

The internet regularly echoes with gasps as new audiences discover Levina Teerlinc, Tudor ‘paintrix’ (as she was described in records from the time). There is surprise not only at her employment in the Tudor Court but also at the respect she received at the highest levels: she was better paid than male artists such as Hans Holbein and Lucas Horenbout.

After her death, general awareness of Teerlinc’s life and work fell away, but over recent centuries scholars have unearthed evidence of her career as an artist through account books of wages and New Year gifts. The documentation, however, provides only an outline of when Teerlinc was at court and what her roles might have been. As yet, it has not provided a list of extant works that can be definitively attributed to her, and her oeuvre remains the subject of debate. Nor do the records provide insight into her as an individual – her beliefs, emotions, formative experiences or memories.

Contemporary novelists have leapt into these gaps, speculating within what is known to create possible versions of Teerlinc’s life, part of a wider movement to portray the ‘lost’ lives of historical women (take, for instance, the many renderings of the artist Artemisia Gentileschi in literature, theatre and film). There are a surprisingly large number of novels featuring the lesser-known Teerlinc. She has a key role in Elizabeth Fremantle’s Sisters of Treason (2014), for example, and is a supporting character in an array of historical fictions, mysteries, and even young adult novels.

Working from the same archival materials, the authors create multiple Teerlincs who differ in personalities and talents, depending on the writers’ narrative needs. Their fictions have a double function: through this accessible medium they reinscribe a marginalised female artist back into popular understandings of the past, while also provoking audiences to consider which other figures might have been lost.

What happens, then, to the ‘real’ Teerlinc amid these circulating fictional portraits? One risk is that such fictions overshadow or distort what is known about the Tudor paintrix. When successive eras remake historical figures in fiction, this often reveals more about the desires of the present than it does about the past. Conversely, these novels may prompt readers to further their own knowledge of the person and time represented. Regardless of how closely these speculative portraits align with the ‘real’ Teerlinc, the renderings keep Teerlinc’s memory alive within popular culture. They offer possible answers to questions about who she was and what her life was like. None may be accurate, but each portrait creates a space to wonder – about Teerlinc, and other women artists like her.

Catherine Padmore teaches literary studies and creative writing at La Trobe University, Melbourne.

Joan Carlile

Portrait of an Unknown Lady 1650–5

Photo © Tate

Anne Killigrew: The Vanity of Public Recognition by Tabitha Barber

Anne Killigrew was celebrated as a virtuous young woman, skilled in the ‘sister arts’ of poetry and painting. But social convention dictated that Killigrew’s work be private. It was only on her death, through the publication of a quarto book of her poems, that it was made public. Poems by Mrs Anne Killigrew (1686) was prefaced with a flattering ode by the court poet John Dryden, a transcript of the epitaph on her funeral monument and a mezzotint frontispiece of her own self-portrait. Her poems that follow include ‘Upon the saying that my Verses were made by another’. Indignant that her poetry (that circulated privately in manuscript) had been ascribed to another author, in this poem Killigrew chastises herself for the impure vanity of wanting public recognition. Exposing herself on the public stage in this way would have been regarded as wholly improper – the opposite of the ‘sweet saint’ she was fashioned as in her posthumous book of poems.

Later, the poet Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea, admitted that while at court she had never been imprudent enough to make her poetry public. In ‘The Introduction’, she speaks of the criticism levelled at women ‘who intrude on the rights of men’ instead of keeping to ‘good breeding, fashion, dancing, dressing’ and the concern of household management.

Both women make clear the social boundaries that the early modern world set for women, beyond which it was improper to stray: a woman’s sex could obstruct her fame.

Tabitha Barber is Curator British Art, 1550–1750, Tate Britain

Henrietta Rae

A Bacchante 1885

Private collection

A Moral Outrage: Henrietta Rae’s Genteel Nudes by Alison Smith

The 1885 Royal Academy exhibition was one of the most controversial the august institution had ever seen, as a ferocious debate exploded over the number of nudes on display, and over whether it was appropriate for women to gaze upon the unclothed human body, let alone depict it themselves. One of the women to exhibit a nude painting in 1885 was Henrietta Rae with her debut, A Bacchante. It shows one of the followers of the ancient god of wine and festivity holding a thyrsus (a symbol of fertility) in one hand while reaching up to pick a bunch of grapes with the other. The classically posed figure is white and hairless, as per European academic conventions for representing the female body.

It all kicked off when some very loud and very effective evangelical ‘purity’ campaigners focused their energies on the alarming emergence of women as professional artists. There had been longstanding anxieties over the moral position of female artists’ models, but it seemed some women artists were now colluding in the degradation of their sex by showing nudes in public. Rae was astonished to receive a letter from what she called ‘one of those self-constituted guardians of artists’ and the public’s morals’ urging her to cease perverting her artistic gifts by exhibiting nudes. Rae, who had just given birth, saw no impropriety in representing the human form as created. Her bacchante is not a riotous cavorting pagan but rather a genteel woman transposed into a garden setting, which was presumably precisely what some found so offensive about it: she looked perhaps too much like younger female members of the Academy audience. Hence the paradox of the first female painters of nudes: to make their subjects homely – rather than openly lascivious – was paradoxically to make them all the more threatening.

Alison Smith is Chief Curator, National Portrait Gallery.

Laura Knight

A Dark Pool c.1917

Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne. Photo: Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums/ Bridgeman Images

Women at the Slade by Jan Marsh

Young Ada Marshall was about to enrol on a part-time course at the Slade School of Art when she glimpsed in the studios a model, ‘all but unclothed ... being drawn by men & women together’, and promptly fled home. Founded in 1871, the Slade was famously ‘open to male and female students on precisely the same terms, and giving to both sexes fair and equal opportunities’. Life drawing sessions, elsewhere mostly unavailable to women, were a prime attraction.

At first, women and men were segregated in the Life Room – as was traditional in British art schools until at least 1918 – but by 1881, illustrations show them drawing together at the Slade. The appointment of Frederick Brown as Professor of Art in 1893 led to further liberalisation of practices concerning women drawing from nude or nearly nude models. The Slade soon gained a reputation for open-mindedness, and while such approaches might have proved too much for Ada Marshall, who never did go on to seek a career in art, there were plenty of other women eager to take up the opportunity. By 1895, of the 310 students in the Fine Art department, 206 were women.

Life studies by the likes of Elinor Adams, Eileen Lambton and Ida Knox – many of which also display the paraphernalia of the teaching studio – won prizes in student competitions. However, in general, women had little success in claiming the most prestigious awards, and, when they graduated, their work was less likely to be accepted into the esteemed, progressive (and effectively Slade-controlled) New English Art Club.

Additionally, women battled perceptions of art training as a suitable ‘feminine accomplishment’, and of schools, including the Slade, as merely respectable places to send daughters before they were married. Such views led to a pervasive belief that few of the women enrolled had any intention of pursuing art as a serious career. Tutors were inclined to treat women – regardless of their true commitment – as hobbyists, and many were therefore discouraged.

While women may have made it into the Life Room by the end of the century, their fight for equality in the art world was just beginning.

Jan Marsh is a biographer and curator. Her latest book is Elizabeth Siddal: Her Story (2023).

Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520–1920, The Linbury Galleries, Tate Britain, 16 May – 13 October.

In partnership with Lockton. Also supported by Julia and Hans Rausing and The Christian Levett Collection with additional support from the Now You See Us Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate Patrons and Tate Members. Exhibition curated by Tabitha Barber with Tim Batchelor.