When my father arrived in London in the winter of 1962, I think he experienced something of a culture shock. Back in India, the idea of Britain had always exercised a kind of magical spell on him, but the reality he faced when pursuing his ambition to become an artist was very different. While meeting supportive people such as fellow Indian artist F.N. Souza had a profound and lasting effect on him, South Asian art was very much marginalised at the time. Apart from galleries such as poet Victor Musgrave’s Gallery One and the New Vision Centre, where Souza, Avinash Chandra and Anwar Jalal Shemza showed their work, there were few opportunities for those who were labelled ‘Commonwealth’ artists.

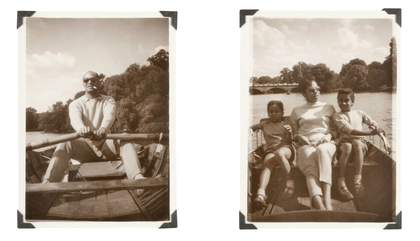

My father soon met my mother, Francine. Following a motorcycle accident, he went to recuperate with her family in Metz, France. This proved a balm to the wound of coming to the UK and not finding the embrace of society. He had experienced discrimination, both in his personal life and in the art world, but among my mother’s family he found a more welcoming place. Here he could focus on developing his work, free to experiment and find his way. Eventually, he had the opportunity to exhibit at the New Vision Centre in 1965, at Antony Tooth’s gallery in 1966, and, in 1968, at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. His confidence in his chosen path grew.

In 1965, both Balraj’s father and brother-in-law passed away. There is a darkness to the work that he made in this period, which has to do with his feeling of loss. Autumn Forest 1965, one of three paintings recently acquired by Tate, was made during his time in Metz. If you look closely at it, you can see foliage, branches and shadows; it is a testament to his love affair with the forest. He came from Punjab, a part of India that was half forested, and he lamented that his contact with nature dwindled after moving to London. In Metz, he reconnected with the natural world, going to the forest just outside the city with my mother’s sisters and brother, a reminder of the childhood hunting trips he had taken with his father.

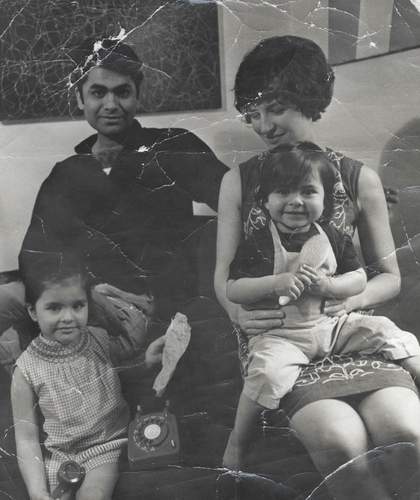

Balraj Khanna with his wife Francine and young daughters Rani and Kaushalia in London, 1968

© Estate of Balraj Khanna

In another painting made a couple of years later, Saffron Field 1967, there is a shift in mood – a move past the thick of the forest towards something more open, a clearing. In India, saffron is a sacred herb used in religious ceremonies: it is the colour of fire and purity. So there is a deep spiritual resonance and sense of healing conveyed through his use of this colour. A square painting, it is made up of small shapes controlled by a meandering piece of string, which gives the painting a gentle sculptural quality and evokes the idea of a flower, or a pen that has drawn a line on the canvas. To me, it suggests a stream-of-consciousness journey along a pathway, connecting the regions he had come from and, perhaps, the new places he was going. Along the way, there are specific areas that one is drawn to – little zones of geometry. In this way, the painting reflects the huge geographical and cultural shifts that my father was experiencing on his personal journey.

I was born in 1967 and I remember how, in the early days, my dad would always paint at home. The house was more of a studio than a home – his work was everywhere. As kids, my sister and I put up with it, because we thought everyone’s home was like that. He was always either sitting at his typewriter or painting, and it never bothered him to be working among the household. On the contrary, the more we were all around him, the happier he was. He would often ask us to participate in some way. For example, we were allowed to pull off the string embedded in his paintings, which he had put there to structure them. Or later, when he moved on to a new visual language, using differently shaped stencils laid on top of the canvas, he would ask us, ‘Guess how many shapes?’ before we were invited to remove them to reveal different layers of the painting. He was quite playful and fun to live with.

I remember him painting Festival 1970, which was a big canvas – 360×180cm – that took up the whole dining room floor. I was about three or four at the time, and I would have to walk all the way around it to get to the kitchen or bathroom, trying not to fall into it. The festival in his painting is completely abstract and undefined, but you can see that it’s populated, it’s crowded – a lot of festive things are happening, even if we’re not quite sure what they are. Festivals are a universal subject; every country has a festival of some kind. When I asked my dad about the painting, he told me it was about expansion. He was thinking about expanding movement on the canvas, just as the universe is constantly expanding, while also challenging himself to make a bigger piece of work.

That painting stayed in our home for many years and was exhibited at the Commonwealth Gallery in the early 1970s, the Serpentine Gallery in 1979, the October Gallery in 1980, and, in 1989, at the Hayward Gallery as part of the landmark exhibition curated by artist Rasheed Araeen, The Other Story, for which my father was also on the advisory committee.

My dad was always committed to doing his best to make things happen for other artists as well as himself, curating exhibitions to promote South Asian art and culture to the wider community. With his involvement in The Other Story, he felt he had the opportunity to contribute to decisions that might result in the country’s cultural gatekeepers changing their understanding of art history. This was one of the highlights of his career, alongside joining the Indian Painters Collective in 1964 and his co-founding of the Indian Artists UK organisation in 1976.

His later painting Out of the Blue (2) 1987 was also included in The Other Story and stems from a period of work, begun in the later 1970s, when he used stencils and spray paint to create diffuse bounds of colour, evoking the sensation of a background, a foreground, and undefined things hovering in space. He became a grandfather in the same year, and I think being around the little ones inspired him to revisit his visual language in a very playful and free way. His work became very gentle, and very lively and colourful at that time. The layering of space in Out of the Blue (2) suggests a skyscape and a horizon line, with forms that could be read as astronomical shapes literally coming out of the blue. Equally, the painting could offer a glimpse of microcosmic life in the sea. My dad had a great affinity with the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore – the abstraction of his imagination – and was always fascinated by the mystery of the beyond, eternity, and how life began. He explored these ideas on both a micro and a macro level in different paintings.

When he first embarked on this new style, he used an instrument that consisted simply of two fine tubes with a space in between, through which he would blow. Drawing from lots of little paint pots around him, he would judge the intensity of the angle and the intensity of the colour he required. His approach was quite spontaneous, but to be able to achieve the effects that he did, he had to know what he was doing. (I once had a go myself alongside my dad, and it just didn’t come out right.) This process also put part of himself into his work. He was blowing his energy into the canvas. Later on, he got a spray gun, which allowed him to make these paintings on a bigger scale.

Slowly, he wanted to bring even more life into the canvas. The crease-like forms that appeared on the surface of his works when spray painting them reminded him of dunes in the desert. A natural development of this was to add some texture, adhering different types of builders’ sand to the canvas when priming it. He quite liked the idea of using whatever materials he could find easily, organically finding these elements, or the working tools, to suit his purpose.

My father was very excited about the prospect of his paintings being acquired by Tate and the display of his work at Tate Britain. He learned about it late last year, not long before he died, and I think he was very proud of himself. He considered it a great achievement. The experiences I had growing up around his art have had a deep effect on me as a person. My dad would never tell us definitively what we were looking at in his paintings. He left it completely open for us. And what he might have seen, he kept very much to himself.

In front of his work, you can invent your own world and make up stories about what you see. And every time you view a painting, there’s something new. It’s never the same. To this day, I like to think that an artwork is an open-ended thing. It’s never something that one should grasp completely and know everything about. A mystery always remains.

Autumn Forest and Saffron Field were purchased with funds provided by Tate International Council and the Nicholas Themans Trust in 2024. Out of the Blue (2) was presented by the artist in 2023. All three paintings are included in the free collection display Balraj Khanna: Theatre of the Natural World at Tate Britain.

Kaushalia Khanna is an architect, designer and creative director based in London. She is also a painter and is working on archiving and establishing the groundwork for the legacy of Balraj Khanna.