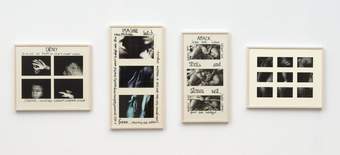

Pictures from Ingrid Pollard's parents' photo albums showing the family rowing a boat on the Serpentine in Hyde Park, London, c.1961

© Ingrid Pollard

When my parents were courting, my father made two photo albums – one for my mother and one for himself. They were a very sweet gift, and very well made.

They contain pictures of my parents’ early life in Georgetown, Guyana. They seemed to go swimming in the ‘bush’ – or countryside – a lot, and many of the blokes seemed to do weightlifting. My mother’s twin brother had a friend who was ‘Mr Guyana’, so there are lots of photos of them doing muscle poses near the coastal seawall in Georgetown. Even as an adult, I liked to sit with my mother and go through the albums while she recalled the usual stories about the people in the photos.

Gradually, pictures of me and my sister appear. There’s one in which we’re sitting together on a step; I’m in between her legs and I look like such a tiny baby. There’s another very nice one of my mother holding me. I must be just a few months old and she’s really laughing.

I know a lot of people my age who say they’ve only got a few, or no, pictures of their parents or themselves as children, so I know I’m very fortunate to have these.

A few years after they married, my father left Guyana for the UK. He had worked as a letterpress setter at the Chronicle newspaper in Georgetown and was recruited as a printer in London. He saved up for six months and then my mother went over to join him. My sister and I eventually came over when I was four years old, by which time I had forgotten who my parents were. I still have a sense of a great loss now as an adult. I think I arrived in London in a state of shock, which might be why I’ve always had such an emotional attachment to the albums.

When I left home, in the late 1970s, I bought my first second-hand camera and eventually made myself an album in the same style, which I still have today. Pictures in an album feel different to those you might keep on your phone. It’s as if you look at a photo on your phone to confirm some sort of memory. But with my album, I bring myself to the photo. It’s about having a physical object – and all the memories that come with it.

I became custodian of my parents’ albums when they died. In my artwork Oceans Apart 1989, I wanted to tell a more individual, personal story of the generation that arrived from the Caribbean in the 1950s. In one panel, under the text ‘wish you were here’, I mounted two photos taken from the albums – the ones of us rowing on the Serpentine in Hyde Park.

I must be about eight years old, and my parents both look very glamorous. I don’t remember being there, but I remember the photo: it fixes that moment for me. Without the albums, I wouldn’t have that.

Ingrid Pollard’s Oceans Apart is included in the touring exhibition Life Between Islands: Caribbean- British Art 1950s–Now, Art Gallery of Ontario, until 1 April. The Cost of the English Landscape 1989 is included in the display No Such Thing as Society: 1980–1990, Tate Britain, and further work appears in the exhibition Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970–1990, Tate Britain, until 7 April.

Ingrid Pollard is an artist and photographer who lives in Northumberland.