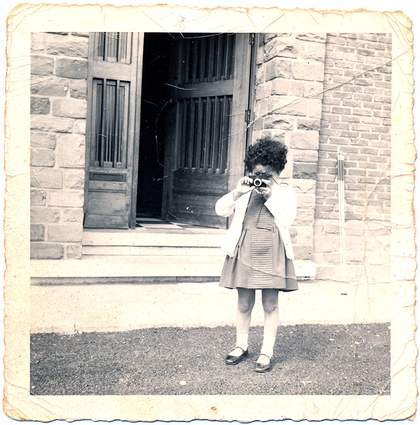

A photograph from the Sedira family album showing a young Zineb in Willebroek, Belgium in 1966

Zineb Sedira

When I was quite young, maybe five or six, my father would take me to art classes. Every Saturday, he would walk me there and then pick me up an hour or two later. It was a kind of ritual. These were very special moments with my dad, when I didn’t have to share him with all my brothers and sisters in our small, overcrowded flat. I come from a working-class Algerian immigrant family in Gennevilliers, a suburb of Paris. There was very little money for such a large family, so for my father to allow me to do those classes was quite a treat.

Around the same time, my father also used to take me to the cinema. It was a small populist cinema, quite rough, nothing fancy. I remember watching Egyptian films – mainly love stories and dramas – and Italian sword-and-sandals or Spaghetti Westerns. The Italian films were great because of the flamboyance of the costumes, make-up and set designs. The colour film stock and processing of the 1960s created ultra-saturated and vivid colours. It was just magical, full of shimmer and glamour.

From the age of 13 or 14, I started going alone to an arthouse cinema called Cinéma Jean-Vigo, which projected many militant, anti-colonial, anti-capitalist films. Gennevilliers was, and still is, a communist town, so unsurprisingly we grew up with such films. Although my parents never told us about the Algerian War, a war of liberation against France, and what they endured, kids are like sponges and somehow absorb what is around them. France lost Algeria in 1962 and I was born in 1963, so you can imagine how palpable racism was back then, with the general French population and ex-colonisers awfully angry towards the Algerians.

When I was around 18, I got to know many painters, musicians, designers and photographers, some of whom had just finished at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Suddenly, I was surrounded by this wealth of creativity, and I was a part of it. We used to go to the cinema all the time to see arthouse films, especially La Nouvelle Vague (French New Wave) and Italian neorealism. By that time also, in the early 1980s, a few French-Algerian filmmakers and writers were just starting out making feature films on social issues that concerned them and their community. I kind of attached myself to them. It was a way to fight racism together, I guess.

Looking back to the art class that my father took me to, it was a very happy place – and perhaps one that I’ve tried to recreate later in life. Today I’m lucky that I can say that, when I make art, it’s a special, enjoyable moment – one in which I can share ‘stories’ with others.

In North African societies, it is often the mother who passes on the traditions, the rituals – especially to their daughters! So, when I tell my dad, ‘Dad, do you realise, if I’m an artist today, it is thanks to you?’ and he smiles back, it is not only because he doesn’t really understand what it means to be an artist, but also because he is so proud of having contributed to my upbringing, to who I am now.

Zineb Sedira is an artist who lives in London. Her film Dreams Have No Titles 2022 was purchased with funds provided by Tate International Council 2023 and is on display at Tate Britain.