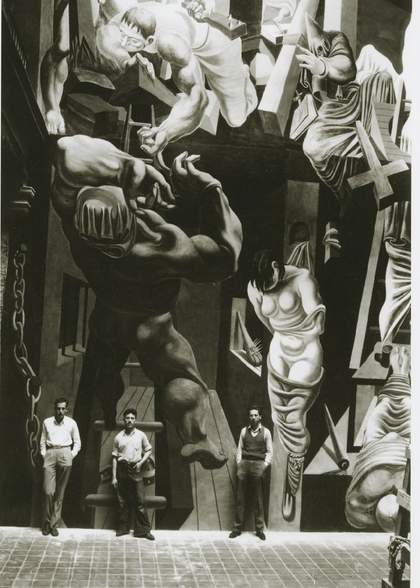

Philip Guston, Reuben Kadish and Jules Langsner in front of their fresco The Struggle Against Terrorism, 1935, in Morelia, Mexico.

Image courtesy of The Guston Foundation

What does bearing witness to violence and terror require? Can art, and portraiture in particular, be a vehicle for social change? Where and how does racial difference matter in museums, and in everyday life, now? Through its didactics and modes of display, Philip Guston has prompted these and other questions as it has toured from venue to venue around the United States.

The retrospective’s arrival at Tate Modern marks the first UK exhibition of the American artist in nearly 20 years, framing one of the leading figures of New York’s modern art scene as both a cutting-edge painter and a critic of white supremacy. Among its many ambitions, the exhibition aims to narrativize the artist’s controversial responses to the racial violences and iniquities of his time. It highlights the confluence of art and racial satire that was ever present in Guston’s work and which has since been carried forwards by new generations of artists, especially African American artists.

Born Phillip Goldstein in Montreal in 1913 to Jewish-Eastern European émigrés, Guston changed his name in 1935 while living in Los Angeles. By this time, he was already well known for his sociopolitical drawings and paintings, and had begun drawing his infamous hooded figures – representations of the Ku Klux Klan, a white supremacist group still active today, who terrorised African Americans with vigilante lynchings and cross burnings, and regularly targeted Catholics, Jews, immigrants, leftists and other groups. In Guston’s Drawing for Conspirators 1930, the dramatic modelling of the foregrounded figure’s robe, his posture, and the rope he holds in his oversized hands creates a looming presence. In the background, Guston analogises lynching and crucifixion, punctuating the visual weight of the rope, which is strewn over blocks that take the shape of Louisiana and Mississippi, two Southern states in which the KKK were most active. This drawing was the basis for Guston’s painting Conspirators 1932 and launched his multi-decade investigations into art as social critique, as well as his later explorations into more abstract and absurd imagery.

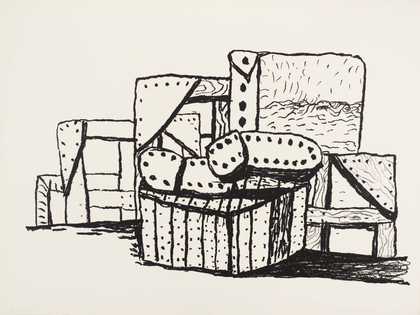

Philip Guston

Painter III 1963

© The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Genevieve Hanson

In addition to Guston’s early encounters with satire, Philip Guston foregrounds the artist’s formative years as a muralist. His early public work, a form of social realism, was greatly influenced by avant-garde movements such as surrealism and Mexican muralism, which positioned art as a vehicle for shock and social change. For the Works Progress Administration, a federal programme that employed millions of people to carry out public work projects, he painted frescos and murals across America, sometimes to a destructive response. Members of the Los Angeles Police Department’s Red Squad, surveilling what they considered to be communist activity, shot and destroyed one of Guston’s murals. Another work, a series of portable panels depicting The Scottsboro Nine – a group of Black teenagers wrongly convicted of rape – was violently damaged by the police during a raid. At small and large scales, these moments point to Guston’s interests in painting as a platform for oppositional politics within the scope of whiteness.

In 1936, Guston’s friend, the abstract painter Jackson Pollock, convinced him to move to New York, where he met other painters beginning to experiment with action painting and colour field painting – the prevailing modes of abstraction at the time. It initiated a shift in Guston’s career, moving away from figuration towards paintings in which clusters of colour congregate at the centre of the canvas. But abstraction eventually proved inadequate – too frivolous – for his political and psychological needs. At the height of the US occupation of Vietnam, the artist returned to figuration as a self-signifying enterprise for exploring the limits and possibilities of his identity: his Euroethnic whiteness, his Jewishness, his maleness.

‘When the 1960s came along I was feeling split, schizophrenic,’ Guston describes. ‘The war, what was happening in America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything – and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue?’ At this time, Guston pivoted back to his hooded figures of the 1930s, allowing the artist to investigate both the schisms deepening within America, and his own wider complicity with racial violence. This was an important moment in Guston’s life and career, with the hooded figure becoming a kind of alter ego – an anti-hero – for the artist.

Philip Guston

The Studio 1969

Promised gift of Musa Guston Mayer to The Metropolitan Museum of Art. © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Genevieve Hanson

Guston’s signature works of the late 1960s and early 1970s depict lines and figure-ground relationships in a style informed by newspaper cartoons from his childhood. Maladroit Klansmen engage in various activities: they drive around with clubs, they smoke and congregate, they stack up bodies in their blood-stained robes. In The Studio 1969, a white-hooded figure with a large red hand sits at an easel where he paints another white-hooded figure. Caught in the act of confronting the self-as-other as the figure recreates his own image, The Studio illustrates a version of the mirror stage theorised by French psycho-analyst Jacques Lacan: an infant, once it becomes aware of itself, develops a rivalry with its reflection – an aggressive tension between the subject and the image that arises from nascent self-awareness. Guston considered his hooded figures to be primarily self-portraits, and this composition can be seen as a metaphor for his own developing consciousness surrounding selfhood and privilege amid cycles of state-sanctioned violence at home and abroad.

Rather than address the questions at the heart of Guston’s project, especially around the status quo of US race relations, New York critics dismissed the body of work as an unfortunate change in style. In recent years, however, Guston’s hooded figures have been cast as progressive, even radical, works of introspection and self-reflection. Though the bulk of the artist’s work from 1972 onwards addressed other subjects, the self-referentiality of these paintings have come to define his legacy. Guston was far from alone in his choice of imagery: the 1970s also saw the rise of Black power politics and of artists of African descent in the United States who incorporated Klan motifs into their work in order to question the persistence of racial violence and stereotypes.

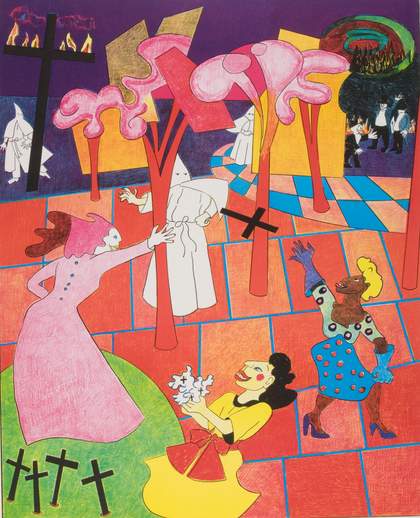

Reading African American artists’ own experiments with racial satire in the late 20th and early 21st centuries alongside Guston’s own work helps to reframe how and when identity politics succeeds and fails within art history, and also within the museum. In part, this reframing situates Guston within structures of power, even as he questioned the implications of assimilation and the ways in which he himself helped to uphold white supremacy. Black artists’ deployment of racist imagery during and after the 1970s, on the other hand, outlines the different ontological and political relationships they occupied against whiteness. Sculptor and filmmaker Camille Billops, for instance, regularly included Klan figures in her work. Her 1994 print The KKK Boutique, titled after the satirical film she made with her husband that same year, features hooded and robed figures hiding behind candy-coloured trees as a cross burns in the distance. The film The KKK Boutique Ain’t Just Rednecks that inspired the print addresses the origins, stereotypes, violent histories and agendas of racism, pressing viewers to confront their own potential for, and participation in, subjugating people who are different from themselves.

Camille Billops

The KKK Boutique 1994

Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of the Brandywine Workshop, Philadelphia, in memory of Anne d’Harnoncourt, 2009

Other artists working at the time, including Michael Ray Charles, Joyce J. Scott and Beverly McIver, explore what art historian Richard J. Powell calls Black visual satire. These forms of antiracist dissent and introspective critique tackle the persistence of blackface minstrelsy in popular American culture. Charles’s 1995 screenprint 24/7 – its title a reference to the hypervisibility of Blackness in contemporary global culture – bridges the jester figure with blackface minstrels. The text in the image, ‘Forever Free’, refers to the false promises of US democracy, further underscoring Charles’s satirical approach to entertainment, advertising and print culture. Scott’s Birth of the Mammy I 1999 portrays the mammy stereotype as a powerful, inflamed entity set to wreak havoc. Among wire coils of red beading, she holds an outstretched, contorted figure in her arms. Is the figure a child? An alter ego? Another female form? A kind of twin image or doppelgänger? Alternately, is it a scene of rage? Of revenge? Of mutualism or retribution? Beverly McIver’s Smiling White Face 1 and Smiling White Face 2, both 1996, depict the artist in extreme close-up in traditional clown makeup with exaggerated red lips – an inversion of minstrel imagery that troubles the binary between Black and white, self and other. All of these works disrupt the ways in which viewers have come to see and know difference and otherness in the West, turning the visual signifiers of racial hierarchy on their heads.

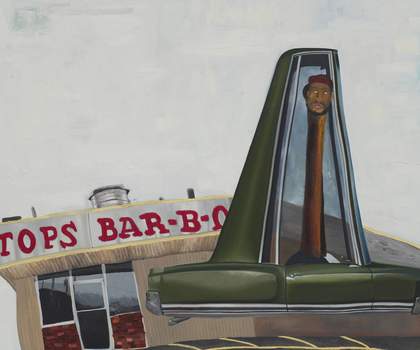

Self-taught artist Brandon Deener’s Flying Around 2021 directly takes on the prominence and efficacy of Guston’s legacy within modern and contemporary art, reimagining the artist’s Riding Around 1969. Though the compositions of the two works are similar, their regional and aesthetic differences abound. Born in Memphis, Tennessee and based in Los Angeles, Deener paints himself into his scene, altering the original to depict a different kind of satirical critique, levied at the predominantly white art world. By transposing key elements of Guston’s painting (the Klansmen, the factory), he transforms what counts as artistic genius – a label typically reserved for white male artists. With characters that hover above the ground in scenes of leisure rather than terror, Flying Around presents an alternative representation of Black subjects that also challenges who can lay claim to the region and the legacies that shape it.

Brandon Deener

Flying Around 2021

© Brandon Deener. Courtesy Simchowitz Gallery

Trenton Doyle Hancock’s ‘Step and Screw!’, a series of 30 works on paper initiated in 2014, additionally re-evaluates Guston’s rendering of the Klan. In the series, Hancock’s alter ego, a Black, male superhero called Torpedoboy, squares off with the grotesquery and irony of Guston’s Klansman as characters in a sad comedy of errors. The series takes the form of a comic strip that depicts the entangled relationship between white supremacy, Black exceptionalism and the American dream. Late artist Peter Williams’s ‘The N-Word’ paintings – also initiated in 2014, as a response to the murder of teenager Michael Brown at the hands of police in Ferguson, Missouri – similarly riff on Guston. The red and blue palette of the series, the comic book vernacular, caricatured figures and scenes of vigilantism on both sides of the colour line – oversized pigs dressed in police clothing terrorise minstrel proxies as a Black superhero intervenes – transmogrify Guston’s signature motifs. Williams’s thin applications of paint are formal but not careful. They are hurried, raw, urgent in their response to the anti-Black climate of their time. Though Hancock and Williams both centre Black male superheroes, they work towards distinctly different goals that redeploy satire and Guston in divergent ways. Hancock’s series is thematic in its critique of what counts as virtuosic and valuable. Williams is concerned with painting as an act – a performance – of power itself.

African American artists who take inspiration from, and a critical view of, Guston’s hooded paintings (often simultaneously) mobilise satire in a number of ways – from appropriating Klan imagery to using images of minstrelsy to critique white supremacy. In so doing, they reframe the artist’s legacy, expand the boundaries of racial satire, and encourage art historians and museum professionals to reconsider the ethics of exhibition-making in the 21st century. As part of this matrix, the retrospective Philip Guston surfaces the frictions and fissures that emerge when race, art, politics, power and privilege collide. Satire neither relieves nor vindicates racism. It, too, can act like a hood that masks what lurks underneath. In bringing these issues to the fore, the exhibition – and the art it contains – underscores how reckoning with historical trauma and terror demands both the reconstitution of the self and revolution – a dual unravelling that may, if we are lucky, usher in a more just world.

Philip Guston

Riding Around 1969

Promised gift of Musa Guston Mayer to The Metropolitan Museum of Art. © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Genevieve Hanson

Philip Guston, until 5 October 2023 – 25 February 2024. Presented in the Eyal Ofer Galleries. Supported by the Terra Foundation for American Art and Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne. With additional support from the Philip Guston Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate America Foundation, Tate Patrons and Tate Members. Co-organised by Tate Modern, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the National Gallery of Art, Washington, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Tate Modern’s exhibition is curated by Michael Wellen, Senior Curator, International Art, and Michael Raymond, Assistant Curator, International Art.

Tiffany E. Barber is a scholar, curator and critic whose work focuses on the Black diaspora in the United States and the broader Atlantic world. She is currently Assistant Professor of African American Art at UCLA.

Joan Choi is an emerging writer, art historian and museum professional.