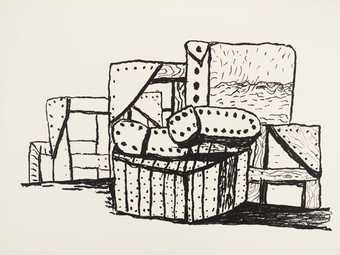

Philip Guston Flatlands 1970 San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (San Francisco, USA)

© The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

MICHAEL WELLEN I thought we would start by talking about your father’s early years. Where did his interest in art come from?

MUSA MAYER It began with cartooning when he was very young, but he also pored over books of reproductions of Renaissance paintings. He would go to the library and spend hours looking at drawings of the old masters – Michelangelo, Masaccio and Piero della Francesca – and made some very detailed copies. There were so many things that he loved about the Renaissance, particularly the large frescoes, that I think his ambition to be a great painter in that tradition was awakened.

MW I am interested in Guston’s early career as a muralist. How did that come about?

MM He carried forward that Renaissance ambition, to paint on a large scale and to tell stories. During the Great Depression, the government supported artists to create murals in public buildings. He completed his first murals in Los Angeles and Mexico, and then won a mural competition in New York, which led to other opportunities. The Federal Art Project nurtured many artists of his generation and gave them experiences that they were able to take into their easel painting. You can see that much of his later work came from the mural projects.

He was also politically aware. My grandparents had moved from Eastern Europe to Montreal, and then to California to escape antisemitism and persecution. But racism was rife in Los Angeles. When he was a boy, you had thousands of Ku Klux Klan members in full regalia marching through the streets of the city. Murals reflected his desire to create art that addressed issues that spoke to the people, that was for everyone.

Philip Guston

Dial 1956

© The Estate of Philip Guston. Digital image © Whitney Museum of American Art/ Licensed by Scala/Art Resource, NY

MW Why do you think he rarely spoke about his work as a muralist?

MM He didn’t talk much about his past work. He was focused on what he was working on in the present. Once he was finished with a painting, he was finished with it. If you read his writings, what you find is that he talks primarily about the artists that he loves, the ideas that preoccupy him, and, most importantly, his own creative process. He doesn’t go into detail about previous paintings and resists talking about the meaning of his own works.

MW So there’s never that kind of nostalgic looking back.

MM No, but you can trace the recurring imagery for yourself. There is an iconography that is ever-present in his works, in the sort of waking dreams of his paintings. Certain images find their way in from the very beginning of his career, and never leave: the hanging lightbulb, the clock, the window shade. In an exhibition like this one, you can see his lifelong preoccupations.

Philip Guston If This Be Not I 1945 Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum. University purchase, Kende Sale Fund, 1945 © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

MW Guston started out as a figurative painter but moved in the late 1940s towards abstraction. What do you think abstraction offered him?

MM Well, he was a latecomer to abstraction. His contemporaries – friends like Jackson Pollock – had made the move much earlier. His figurative work had some success at that point, but he was not satisfied. It’s been said by curator Harry Cooper that the first period of my father’s career was all about finding what to paint. And then the abstract period was about finding how to paint. It was concentrating on the process of painting to allow the forms to come through in a different way. And then those two elements converged in the late work; it’s that convergence I think that sustains the interest in his work overtime.

MW Was there anything else that prompted the shift? I’m thinking, for instance, of Guston’s later comments about his reactions to the imagery of the concentration camps that was circulating at the time.

MM By the end of the Second World War, he was in the midst of a crisis, in part because he found himself unable to create works that expressed the fullness of his horror of the Holocaust and the destruction of the war. In a way, I see that period as being initiated with a completion of If This Be Not I in 1945, which was a sort of summation, he felt, of everything that he had learned about painting up to that point.

But it’s also a period of leaving the Midwest, coming to terms with family life, the allure of New York and the art world there. It’s all somehow related. In the middle of that, he wins a Prix de Rome from the American Academy, and goes to Italy for a year, where he can study his beloved old masters in person. Very little work from that period survives, but he does come back with a wonderful small drawing of the island Ischia, which becomes a catalyst for his first attempts at what Harold Rosenberg referred to as ‘action painting’ – working intuitively and imaginatively without stepping back and analysing the work. And that becomes very important to him, because suddenly he feels like he’s painting in an authentic way again.

That begins his abstract period, which lasts for some 15 years. It’s only in his paintings from the mid-1960s that you can see these dark shapes begin to coalesce into recognisable forms.

Philip Guston The Line 1978 Promised gift of Musa Guston Mayer to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

MW You mentioned how Guston transformed during a period of artistic crises in the 1940s. He faces another transformation in the mid-1960s. Can you talk about that change?

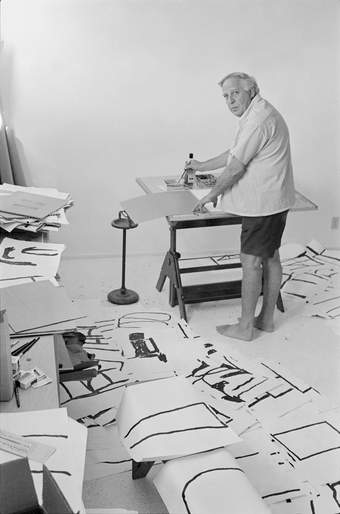

MM The shift coincided with his leaving the art world of New York City, returning to Woodstock, and the building of his new studio there. He begins work on a series of very spare abstract ink drawings – what he called ‘pure drawings’.

At that time, he starts making drawings and little paintings of things: objects, books, bricks, shoes. And from these works, a sort of alphabet of images emerges, and he begins to work on a larger scale. The things begin to multiply, and suddenly he’s creating these huge canvases where he’s assembling whole landscapes and narratives and interiors, and also, around this time, there are the hoods.

MW Yes, one of the most difficult subjects in Guston’s work is the series of images referencing the Ku Klux Klan. Klansmen first appear in his early work in the 1930s, and then they return in the late 1960s in such a different and disturbing way.

MM In Drawing for Conspirators, an early drawing from 1930, you have a Klansman holding a giant rope. And in the background is a sort of crucifixion scene, and the figure of a Black man who has been lynched. It’s a violent and disturbing scene. But in the paintings of hooded figures from the late 1960s he never actually shows the moment of violence.

Philip Guston Painting, Smoking. Eating 1973 Stedeljik Museum, Amsterdam © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

MW There’s evidence of violence, but it’s not an image of the act.

MM It’s already taken place. You see evidence – the blood stains and splatters on everything, on the hoods, on shoes... In some paintings, you see these upturned legs in garbage cans with shoes on – I think these are likely also references to the Holocaust. And they are precursors to his paintings of 1976, which show piles of shoes and legs (Monument or Painter’s Forms II), where he’s turning to the other subject that he felt so unable to render in the 1940s. It finally emerges in a form that he’s able to paint.

MW Do you think it was the images that he saw back in the 1940s that stuck with him? Or do you think he was seeing and thinking about it in a new way because of other things that were happening in the 1970s?

MM I think he was acutely aware of the violence of the world, the genocides taking place, the riots and assassinations. And he was, of course, preoccupied with the genocide of his people, Jewish people. The paintings from 1976 are evidence of that. It’s not that he’s looking at his work in the past and thinking: ‘Oh, maybe this would be a good time to reintroduce this imagery.’ I don’t think it happens that way. I think it happens on an unconscious level, as a way to process what was a deeply traumatic event and find some way through.

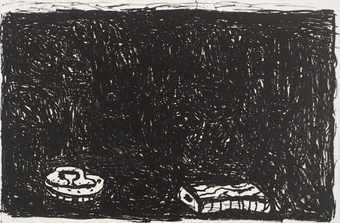

Philip Guston

Painter's Forms II 1978

© The Estate of Philip Guston. Collection of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

MW Trauma works on its own timescale. These images emerge in what was Guston’s most prolific period as an artist. I understand that two-thirds of his paintings were created in the last 12 years of a 50-year career.

MM The 1970s was a prolific period for him: lots of sleepless nights, lots of drinking, lots of smoking, lots of intensity. He couldn’t stay away from the studio.

MW It was also a time when he was connecting with poets and writers. I wanted to ask you about your mother, Musa McKim, her poetry, and her creative relationship with your father. In the exhibition, we’ll include several of the poem-pictures, drawings that bring together his iconography with verses from your mother’s poetry.

MM My mother’s writing really began in the 1950s, when we were living in New York and she was studying poetry with Kenneth Koch, who was an inspiring teacher. But also, because my father was drawn to poetry and poets were drawn to him, there were often poets in the house: Frank O’Hara, Clark Coolidge, Stanley Kunitz. My mother was both a poet and a painter, and she also produced murals in the 1940s. Her last paintings are actually hanging on the wall in my office, once her office.

Philip Guston The Ladder 1978 National Gallery of Art (Washington, DC, USA) © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

MW Yes, I was thinking about how in your book, Night Studio (1988), you recount a memory of seeing her picking up shells on the beach. In the portrait of her that Guston made in the 1940s, she has shells on her lap. I was wondering, what did the shells mean for her?

MM She liked to wander in the natural world and look for objects. It wasn’t just shells – it was leaves, rocks, stones of all kinds, birds’ nests. I’ve got shelves of her collections. One of my fondest memories as a child is of going around with my mother and just exploring and looking for interesting things.

MW So, at the same time that Guston’s paintings often show assortments of objects, McKim was making collections of her own. In a poem-picture like I Thought I Would Never c.1972–5, Guston draws some of his favourite objects – like a book, a pencil, and a lamp – alongside some of McKim’s, like a shell and a nest. There’s a sense of their connection – that the objects have just washed up around the words. Could we talk about his final works, particularly those images of sleeping figures and of objects that are dominated by heavily painted black backgrounds? The exhibition will feature several of these wonderful works, including Sleeping 1977, Couple in Bed 1977, Kettle 1978, Talking 1979 and Flame 1979. The black dominates the surface, but colour is submerged behind. They are thick and luscious paintings.

MM They are luscious, aren’t they? You get the feeling that, even at the end, when he knew that he didn’t have long to live, he still took such pleasure and joy in the act of creating and eating and painting. Those were his preoccupations up to the end of his life. In fact, he died immediately after enjoying a meal with friends. So, even though he keenly felt his approaching mortality, you can see this in all those late black paintings, along with his sense of where the world was going, which we feel now maybe even more strongly.

Philip Guston

Talking 1979

© The Estate of Philip Guston. Digital image © The Museum of Modern Art/ Licensed by Scala/Art Resource, NY

Philip Guston

Couple in Bed 1977

© The Estate of Philip Guston. The Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, NY

Philip Guston

Kettle 1978

© The Estate of Philip Guston. The Philadelphia Museum of Art/Art Resource, NY

MW What would you say is the relevance of Guston’s work for artists and audiences today?

MM The revelatory thing for me – and, I suspect, for others – is how timely his work continues to be. Each successive generation finds their own sense of meaning in the work, and relevance to their own work. I’ve always been impressed by how younger artists are inspired by his willingness to follow his deepest impulses, however they were being received. His willingness to not simply repeat what others have praised.

MW He’s willing to give up so much to start again, he’s willing to let go…

MM Not only does he let go, but I think, with each success, his own sense of doubt is aroused. It’s like he never wants to be comfortable; he is always suspicious of success and feels the need to reject it in some way. I wish he had had more financial success in his life. It’s unclear to me whether the teaching job that supported them in the last decade of his life interfered with his work or, in some way, actually encouraged it, because it brought him into contact with young painters for three or four days a month. He complained about it, because he didn’t want to leave the studio, but, at the same time, I think it was stimulating to him at a time when he was largely isolated.

Philip Guston

Cellar 1970

© The Estate of Philip Guston. Collection of Ann and Graham Gund

MW I find his resilience inspiring, in the sense of being willing and able to push through the doubts and the dark moments and still find away to produce thework he did.

MM It was a lifelong process. I suspect it was learned through surviving catastrophic loss at a young age: his father’s suicide, the tragic death of his brother. Those devastating life lessons present themselves to all of us, eventually. In some ways, it’s almost to one’s advantage to have that experience early, because then you can bring that resilience to your entire life.

The need to find something you love so deeply, to commit yourself to, becomes essential if you are to survive, and that’s what he learned to do as a boy. His friend Ross Feld, in an essay from 1980, talks about how my father ‘drew a distance for himself away from the family’s shock and grief’.

This may be crucial to many who love my father’s work, as it is to me: that he could experience and counterplay the darkest moments of his own life and of his society’s life, and, by transforming them on the canvas and on paper, find a reason to survive and continue painting.

Guston working on his 'pure drawings' in Sarasota, Florida, 1967

© The Estate of Philip Guston. Photo: Renate Ponsold, courtesy of The Guston Foundation

Philip Guston, Tate Modern, 5 October 2023 – 25 February 2024. Presented in the Eyal Ofer Galleries. Supported by the Terra Foundation for American Art and Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne. With additional support from the Philip Guston Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Patrons and Tate Members. The exhibition is co-organised by Tate Modern, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the National Gallery of Art, Washington, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Tate Modern’s exhibition is curated by Michael Wellen, Senior Curator, International Art, and Michael Raymond, Assistant Curator, International Art.

Musa Mayer is a writer, curator, counsellor and President of The Guston Foundation. Her book, Night Studio: A Memoir of Philip Guston, was reissued in April.