Atong Atem

Dit (2015)

© Atong Atem. Courtesy the artist and MARS Gallery

Why did you become a studio photographer?

Hassan Hajjaj (b.1961) is an artist who lives between London and Marrakech. Known for his portraits that mix Moroccan and pop cultural references, Hajjaj’s photographs are in museum collections across the world, including the British Museum and the Victoria & Albert Museum. In 2020, he shot his first Vogue cover featuring the musician Billie Eilish.

HASSAN HAJJAJ In my hometown of Larache, Morroco, there was a shop with a photo studio where all the families would go to get their pictures taken. The shop was downtown, and I would often look at the pictures on display in the window.

We would go there to get family portraits taken to send to my dad, who moved to England in the 1960s. I remember it very clearly. It was me, my two sisters and my mum. You dressed in your best clothing, and my mum would even put on perfume. There was a chequered floor, a curtain behind, and all these props – a small metal racing car, a plastic horse, and cowboy outfits with a gun and a hat.

Something about the props, the lighting and the way the photographer moved and made everybody comfortable – that experience had an impact that has stayed with me, and has since come out in my photography. Thirty years later, in the 1990s, I took my first studio photographs in a riad in Marrakech.

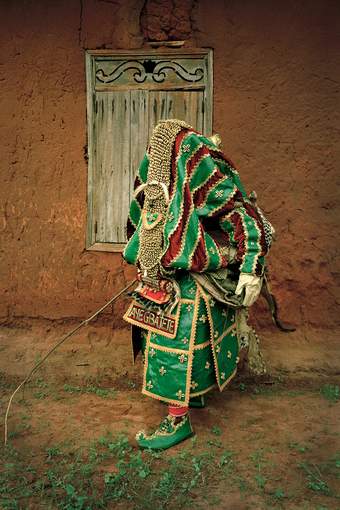

Hassan Hajjaj

Ha Hna (2000/1421*)

© Hassan Hajjaj. Courtesy the artist

Atong Atem (b.1994) is an Ethiopian-born South Sudanese artist and writer who lives in Melbourne, Australia. Best known for her elaborately staged portraits, her work explores the decolonisation of imagery of people from across the African diaspora. In 2022, she won the inaugural $80,000 La Prairie art award for Australian women.

ATONG ATEM I came to studio photography during my early research into South Sudanese history and general African art history. At the time, I expected to see writing and archival photographs from the colonial era and through a colonial lens, but I didn’t expect to see so many dehumanising and troubling depictions of Black people. In hindsight, it was a bit naive of me to have expected something different.

Very quickly, I was introduced to African photographers who had, decades prior to me, grappled with the complexities of representation and developed the revolutionary act of focusing on group portraits. I came to know the works of photographers such as Malick Sidibé, Seydou Keïta, Philip Kwame Apagya and their contemporary counterparts, who created this canon of art that responded to the trauma of colonialism. These were photographers who had illuminated a visual language that was beautiful and intuitive – and I sought to participate in it.

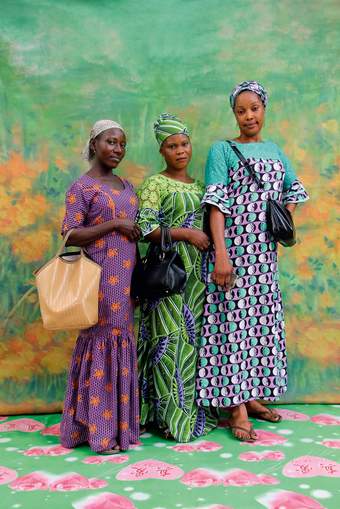

Atong Atem Adut and Bigoa 2015 courtesy of the artist and MARS Gallery © Atong Atem

Ruth Ginika Ossai (b.1991) is a British-Nigerian photographer who lives in West Yorkshire. Her studio portraits feature richly patterned backdrops and floor mats, and celebrate the beauty and power of Nigerian identity. She works between the worlds of fine art and fashion, having collaborated with Nike, Kenzo and Rihanna.

RUTH GINIKA OSSAI I grew up between Nigeria and Yorkshire, and, as a teenager, I used my first snapshot camera to document my childhood in Nigeria to show my Yorkshire family – and vice versa. I particularly wanted to capture Nigerian identity and culture.

We would sometimes visit studios in southeast Nigeria to take portraits with my relatives to mark birthdays or other special events. These photographs showed Nigerian culture unapologetically, and, as a result, I wanted to recreate these sorts of pictures at home. I would make photo albums and sketchbooks filled with collages of my own photographs, drawing inspiration from the Nollywood shows that I saw on TV. I was obsessed with the visual art of photographs before I learned about their technical side.

Over the years, these influences have transcended into my love of studio portraits, especially those that have a social function – such as holding a memory of a loved one, or transporting that memory over distances or through time.

Ruth Ginika Ossai

Yasmina, London (2020)

© Ruth Ginika Ossai

How do you go about composing your pictures?

RUTH GINIKA OSSAI I tend to set up a temporary studio in the sitter’s house or garden, or in my own compound. The flooring and backdrops are sourced from Onitsha, in Anambra State, and the props are from my own collection, family or friends. I use a lot of artificial flowers from my grandmas in Nsukka or my father in Onitsha – they transport me back to my childhood. Sometimes, I invite the sitter to bring along personal items to help tell their story, such as musical instruments, uniforms or tools they might use in their job.

My inspiration comes from Nollywood – mostly Igbo or Yoruba films – as well as everyday life and people in southeast Nigeria. I also have a collection of homemade DVDs of weddings, burials, ceremonies and 1990s gospel music videos from my childhood, which filter through into my photos. When I put up a backdrop, it becomes like a set, and my pictures play with the special effects used in Nollywood films.

I have fun with the styling of each portrait. That element of fun is what a previous generation of African studio photographers – James Barnor, J.D. ’Okhai Ojeikere, Samuel Fosso, Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta – were all about. Their pictures paved the way for me. They don’t use tricks, they’re not glossy. This type of photography doesn’t care for upper-class sensibilities – it’s for regular people.

Ruth Ossai, Student nurses Alfrah, Adabesi, Odah, Uzoma, Abor and Aniagolum. Onitsha, Anambra State, Nigeria, 2018 Photograph © Ruth Ginika Ossai

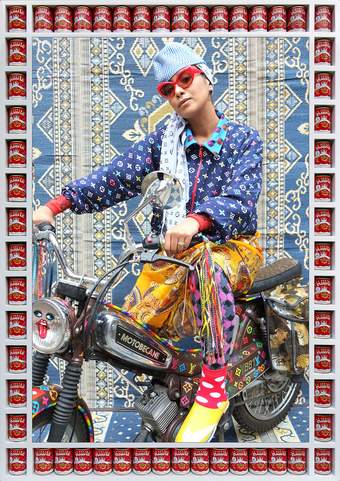

HASSAN HAJJAJ There’s a whole process. First, I think about the outfits. I buy the fabric, draw designs, and have them made by a tailor. I’ve got maybe 2,000 designs ready; they are like my paints. I’m a market person – I live in the medina in Marrakech, close to the souks, and when I’m in London, I live in Camden Lock and visit local markets. I like buying cheap socks and sunglasses, or sometimes interesting clothing, and making them look grand. My aim is to dress somebody for five pounds and make them look like a rockstar.

As for the backdrops, I have a collection of 200 or so mats, which I mainly buy from Morocco. My uncle used to make them when I was a kid. For me, these plastic mats present a working-class look.

When I started 25 years ago, photography was just becoming accepted in the art world. I wanted to add frames, so they weren’t just prints. I started studying 18th- and 19th-century oil paintings, and noticed that they had frames that were specially made for them at the time. I wanted to take that idea and apply it to my pictures. My frames refer to repeated patterns found on Moroccan tiles but are made from things like Coca-Cola cans. They might look decorative, but they have meanings for me. For instance, I might use Spam tins when the guy is ‘beefy’.

Hassan Hajjaj

Gypzee Bikin' (2018/1440) from the series Kesh Angels

© Hassan Hajjaj. Courtesy Gypzee and the artist

ATONG ATEM Most of my works are made in makeshift photo studios – at my home, a shared arts studio space or, in the case of the Studio Series, at a drawing studio at the university I attended at the time.

I’ve always enjoyed the process of portrait photography most, especially when it comes to set building and composition. I think of it as painting – partly because that’s what I was trained in and partly because I enjoy the tactile nature of creating a set.

Most of the props are my own. I find a lot of joy in stumbling upon textiles, clothing, jewellery and knick-knacks in charity shops. I like to have an archive of props that I can delve into when I work – that’s the part that feels most like painting.

There are some very personal objects – mostly textiles – in my work. In I Have Two of Everything from my 2020 photobook Surat, the backdrop is a white, cotton bedsheet called a milaya in South Sudan. This milaya features two elaborate, hand-embroidered peacocks among branches and flowers; it was gifted to me, as is customary, by my mother. These textiles hold strong cultural significance and are a major feature of South Sudanese aesthetic culture.

Atong Atem

Paanda (2015)

© Atong Atem. Courtesy the artist and MARS Gallery

How do you choose your sitters?

RUTH GINIKA OSSAI The sitters for my studio photographs are friends, family or members of my community. For instance, in one picture I took in 2021, I shot my father and Uncle Okey together in Anambra.

I love to photograph people over a lifetime, watching them grow and change in their everyday life, or just marking and documenting special occasions. I recently photographed a friend who is currently pregnant and, once her baby is born, we will shoot her again with her newborn – and then I’ll document her and her child’s life for years to come. This is what I love to photograph. It fills me – and her, I know – with so much joy.

My aim is to be as collaborative as possible with the people I shoot. So, identity and self-expression in terms of styling, clothing, hair and makeup plays an important role in my image-making process. I want people to be unapologetically themselves, whether that is flaunting their culture with pride or by appearing naturally with their personal style or individual personality.

Ruth Ginika Ossai

Uncle Okey Ossai + Daddy (Ruth's Father), Anambra (2021)

© Ruth Ginika Ossai

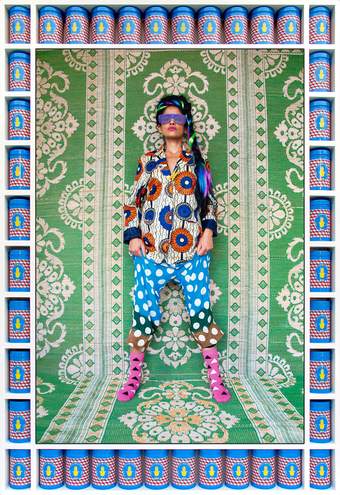

HASSAN HAJJAJ Growing up between London and Morocco, travelling, running club nights, doing music videos and working as a stylist, I’ve had an opportunity to meet many wonderful people. I first started photographing friends, then friends of friends, and so on.

Karima, who is a henna artist, has been in my pictures for over 25 years. I like her personality, her movement in the pictures. She also helps me to find other people to shoot – if I wanted to find some male belly dancers, she would know who to ask.

I don’t come from an art background. As a kid, it wasn’t cool to be an artist, and my friends and I couldn’t walk into a commercial art gallery, because it was too uncomfortable. So I had to teach myself about art. The first artist I discovered was Malick Sidibé, who photographed life in his hometown of Bamako, Mali, capturing its sense of style.

I wanted to do this in my own way: my experience was moving to London from Morocco, so I decided to shoot people with similar experiences – my friend from Brazil who now lives in London, or another from Nigeria who now lives in Paris, for instance. This became the My Rockstars series. I’ve probably shot a thousand portraits now, but there are thousands more I want to shoot. It’s about documenting people who have been scattered around the globe.

Hassan Hajjaj

Alo Wala Standin' (2015/1436) from the series My Rockstars

© Hassan Hajjaj. Courtesy Alo Wala and the artist

ATONG ATEM My work has shifted primarily to self-portraits in the last few years, especially after working on my photobook Surat, which exclusively featured self-portraits. The shift was organic for the most part, but also grew out of a desire to experiment with my relationship to photography, and the ethics of photographing others. I also began to lean into my interest in cultural mythology and the role of photography in creating myths, so self-portraiture felt like an obvious avenue to grow into.

When it comes to photographing others, I almost always work with friends and family. It’s difficult to convey the process from that point onwards, but, after asking my subjects if they’d like to work on a photographic piece with me, the process itself becomes a personal and intimate exchange – often fun and casual but involving a lot of discussion and collaboration.

It’s important to me that the photographs I take of others are made in collaboration with the subject. Often this involves asking them to bring their own props or inviting them to pick pieces from my own collection.

Atong Atem

Studio 85 (2022) from the series Surat

© Atong Atem. Courtesy the artist and MARS Gallery

What does a typical day shooting portraits look like?

ATONG ATEM The Studio Series was photographed on one day in 2015. I had asked a group of friends to meet me at the drawing studio at RMIT University in Melbourne on a particular afternoon, specifying that I wanted to take photographs of them in the style of the studio photos that we all had in our family photo albums. There was a shared understanding of both the history and significance of these kinds of photos for all of us, especially as all the sitters are first- and second-generation African migrants living in Australia. We had a collective understanding that guided the photographic process.

I invited my sitters to bring relevant props and I also compiled a collection of clothes, textiles, plastic flowers and other props to use on the shoot. We listened to music and my friends took turns trying on different outfits, playing with the props, and discussing with me which pieces worked best as backdrops or that complemented certain outfits.

Once we had chosen the set and outfits, directing was mostly about small details. I have very specific ideas about hand placement, angles of the face and minor details, so that is where the directing is very driven by me, and where my role as a photographer is much more prominent.

Atong Atem

Zack and Adella (2015)

© Atong Atem. Courtesy the artist and MARS Gallery

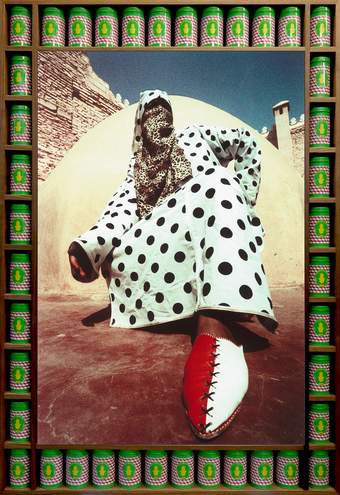

HASSAN HAJJAJ When I’m in London, I take pictures on the street outside my shop, Larache, in Shoreditch, but when I’m in Morocco I shoot inside, in my riad. The studio shoots are more like a performance. Recently, for instance, I did a shoot for the actor Will Smith and some of his friends. We put on a buffet lunch for him, Karima did henna for everyone, and I had a musician play Morrocan Gnawa music. I find the music sets the mood, so people can relax and have a memorable day.

When I put the backdrop down, it’s like a stage; then I dress everyone up and I find that they start to act. It becomes a bit like a performance for both me and the sitter. It’s like I’m a fan, taking the picture of somebody I admire.

Hassan Hajjaj

White Dotted Stance (2002/1423)

© Hassan Hajjaj. Courtesy the artist

RUTH GINIKA OSSAI A typical day of shooting studio portraits is really just me going about my everyday life, shooting real-life experiences with my family and friends. The series I made between 2016 and 2020 was shot at social functions, such as school graduations, weddings, burials, or simply at home with my family in Nigeria.

The picture Student nurses Alfrah, Adabesi, Odah, Uzoma, Abor and Aniagolum. Onitsha, Anambra state, Nigeria 2018 was taken at a graduation ceremony just before the student nurses started their night shift in a maternity ward at a hospital. The image of the three Aunties (Adeniké, Bolatito and Folasade. Ebute Metta, Lagos, Nigeria 2018) was taken at an Owambe or Nigerian party. I had set up a studio at the party, and guests waited for me to snap and print their pictures. And Ogechi and Faith in Ogechi Ugwueze and Faith Ifebuche, Nsukka, Enugu state, Nigeria 2016, are my cousins, who I photographed in my father’s village in Nsukka at my grandfather’s burial ceremony.

I treat the way I document my own life experiences in the same way as any other subject – wishing to fill my sitters with power and agency while not creating pressure. I want to them to be free, and for their own true selves to shine through in my pictures.

Ruth Ginika Ossai

Adeniké, Bolatito and Folasade. Ebute Metta, Lagos, Nigeria (2018)

© Ruth Ginika Ossai

See photographs by Hassan Hajjaj, Atong Atem and Ruth Ginika Ossai in A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography at Tate Modern until 14 January 2024.

Supported by the A World in Common Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council, Tate Patrons and Tate Members. Curated by Osei Bonsu, Curator, International Art, with Jess Baxter and Genevieve Barton, Assistant Curators, International Art and Katy Wan, former Assistant Curator, International Art.

*Hassan Hajjaj's artworks are dated according to both the Gregorian calendar and the Hijri calendar.