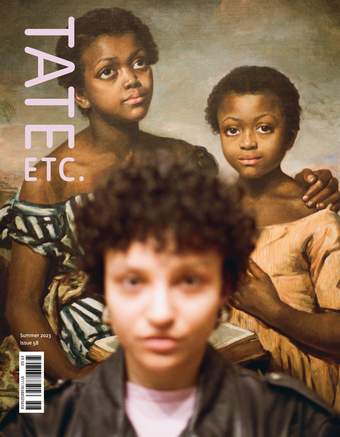

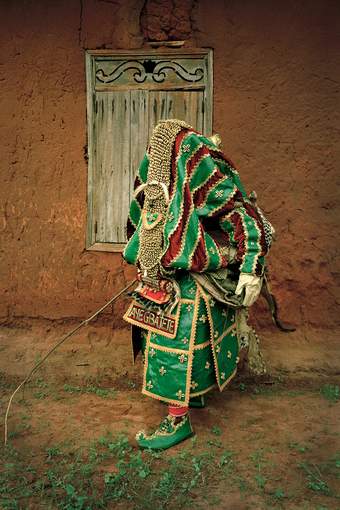

Leonce Raphael Agbodjélou

Untitled (Egungun series) 2011

C-print on paper

Leonce Raphael Agbodjélou. Courtesy of Jack Bell Gallery

Once or twice, aged seven or eight, I told the lie that my father was an Eze, a chief, in our hometown. The details are sketchy, as to what had necessitated peddling the falsehood, except that I remember it was during conversations with fellow pupils.

My school was run by Catholics – some of our teachers were nuns, and every day at noon the bell rang for us to recite the Angelus. And yet it was a period of my life in which I had sunk to such notoriety that I could tell a lie about my ancestry without much heed to the consequences. Even now, I wonder about the need implicit in my declaration. Why did I feel I had to elevate my father’s standing in the eyes of my peers? And why choose a royal title in particular? My hometown has no monarch, as is the case for many Igbo communities. My statement was doubly a lie. My father, in fact, was a clergyman.

I remember being a boy with recurring daydreams of being someone other than who I was: an actor, an inventor of a car, the writer of a 1000-page Bible concordance. I considered each of those identities for lengths of time, thinking of possibilities, such as what tools I would need to build the car or compile the book. I wondered about this particularly while I walked home from school, on a stretch of road between the gate of the large compound owned by the church and the manse we lived in.

The notion is to find a self that is large enough to contain all the potentials we think we possess – just as a masquerade, with its unrevealing form, signals the tantalising promise of an alternate life.

George Osodi

HRM Agbogidi Obi James Ikechukwu Anyasi ll, Obi of Idumuje Unor (in Palace), 2012

George Osodi

The ivy sways lightly, or maybe it is just atremble in Jonathan Adagogo Green’s mind, when a porter stretches a hand to lift him aboard.* A barefoot man stands guard at the rear. Adagogo considers the light and begins to ready his gear. He finds a stool to stand on, in front of which he places his tripod. He sees the guard’s face relax but knows at once that the man hasn’t been born close to the Bonny River, and communication beyond gestures is impossible. He sends over a little wave, and the guard passes back a demure smile. Another soldier, of a higher rank, rests his feet on a large metal box. He is likely the captain of the Protectorate Force Adagogo had heard about, even though it now seems impossible to believe a white man without a trace of hair on his chin is as merciless in warfare as has been reported. The captain looks over Adagogo’s equipment, and nods as if impressed. But his face remains stoic.

Adagogo had woken up surly – such little time he’d had to prepare for a trip to the bank of the river where an undisclosed prisoner is held in a moored steam yacht, a quarter day’s journey. He responds to the captain with deferential ‘yesses’ and ‘ahas’, the minimum expected from him as a man minor in prestige. ‘How soon will you be ready?’ the captain asks Adagogo. ‘Now sah,’ he replies, then pulls out the lens.

The king and his cortege are lifted out of the underbelly of the yacht, about five in all, including two sword-bearers and his head wife. Adagogo has covered his head with a red cloth in near readiness to press the shutter button, and so sees them first from behind the camera. When he raises his head, he shudders at the sight. The king is led forward between two guards, chained from foot to neck. The rumours are true. Britain has conquered Benin. The Oba is on his way to be exiled.

In the first photograph, Adagogo has taken precise note of the Oba’s discomfiture. The right arm of the soldier to the left is sliced out of the frame. After he presses the shutter, he climbs from his stool and looks around. In all this time, he hasn’t sought to make eye contact with the king. He sees a wicker chair, then formulates a question to the captain. ‘Yes,’ the captain agrees, ‘he can sit.’ Of one of the sword-bearers Adagogo asks that the king is dressed in a different manner. He returns to his camera to pull out the used plate, then inserts another.

Adagogo finds the king’s face through his viewfinder. The off-white wrapper has been replaced with a velvet cloth, embroidered with royal swords. The king looks at the photographer with piercing recognition, and, just before the shutter is pressed, tenders a relaxed face.

* Jonathan Adagogo Green, who described himself as an ‘artist photographer’, lived between 1873–1905 in Bonny, one of the most successful precolonial city-states in the eastern Niger Delta region of Nigeria.

In my childhood presbyterian church, a harvest thanksgiving service was organised each year. Perhaps it was a homage to a colonial-era society consisting of newly converted farmers, in which the laity brought an offering of produce to thank God for a good bounty. On such Sundays, a group of children were billed to make a presentation, consisting of either a song based on the theme of fruitfulness, or a playlet of a similar moral. That year we rehearsed a dramatisation of the story of Cain and Abel.

I was chosen to play Abel, and an older boy was asked to take on Cain’s role. As in the biblical story, we were expected to present a burnt offering to God.

First, we carried a basin of goods from one end of the church to the other, in turn. Then, close to the chancery, we dropped the basin, and sang. ‘Nara aja di ka nke Abel, a nara ya di ka nke Cain.’ Receive the offering like that of Abel, and not like Cain’s. After this song, we were to try and set fire to the content of our basins. To signify whose offering was accepted by God, mine, which had been filled with dry grass, was to come alight, while the older boy was to seek fire without success.

Yet, at the appointed time, I could not light the match. I held the stick at the wrong end, repeatedly eliciting no spark. The adults broke into sniggers. The older boy, done with dramatising his part, took my matchbox and lit the offering at the prompting of the Sunday school teacher who was supervising from a corner.

When we were done, the teacher was livid. ‘I asked you if you knew how to do it, and you kept saying, “I know, I know,”’ she said. ‘Why didn’t you just let me teach you?’

For many years afterwards, each time I returned to the feeling of shame that followed, I could not decipher why I had claimed to possess a skill I didn’t. Perhaps I was already conditioned by the fear of being seen as deficient in some way by the boys with whom I attended Sunday school. We were all competing for a trophy of exceptionalism, it seemed, to be awarded to any of us whose mock pose showed the most sophistication.

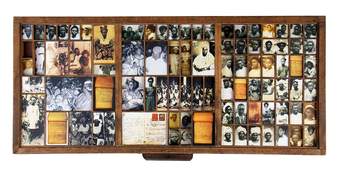

Kelani Abass

Casing History 1, 2016

Letterpress type case and digital print

Kelani Abass. Courtesy of 31project, Paris

During my final year in university, I was the chairman of a committee designated to organise the activities that would mark our graduation. One such event was a class dinner, in which we all dressed up, ate lavish meals, and gave awards to those who had been voted by others as best in this or that. In addition, we were to contract the production of shirts with each person’s name on it, to be worn after our final exams when we’d move through the school in a carnivalesque mood. Last of all, my team and I were to produce a yearbook, which was to include the details of a pre-filled form submitted to us by our peers. To bear these costs, we levied each person 7,500 naira.

In retrospect, I see how we should have prioritised the yearbook, the shirts, and then the dinner, according to the order in which we could best memorialise our years together. But the inverse was the case. By the day of our graduation, we had paid only a quarter of the sum agreed for the yearbook and had nothing left.

Months later, I returned for the convocation ceremony. By some intervention – the details of which are now hazy to me – the printer of the yearbook had agreed to forego the debt we owed, due in part to the reality that we were an unofficial organisation who could not be litigated. So we convened in the lobby of our faculty building to distribute the books. The process went without a hitch and marked, for me, the end of a tumultuous period of bearing the burden of crushing responsibility.

Almost a decade and a half later, I remember a detail of that afternoon that I must have suppressed in the time since. One of my former classmates was visually impaired. While we were students, everyone in the class had done their best to accommodate his needs, whether by allowing him access to the front row of every lecture room or leading him to any part of campus he wished to go when he seemed stranded. As we sat waiting for those who were yet to pick up their books, he heard my voice and asked to speak with me.

He told me how, all those months ago, I had agreed to arrange for him to attend the class dinner, and yet left him waiting. He’d called me to ask for my help, and I had promised to send a car for him, which never came. That day, he recalled in a quivering voice, he had been waiting in front of one of the male hostels when it began to rain.

As I write now, I struggle to remember his name, and feel as guilty as I did then, when I pleaded for his forgiveness. It is as though I have been presented with an album of family photographs and I cannot tell one forebear from the other.

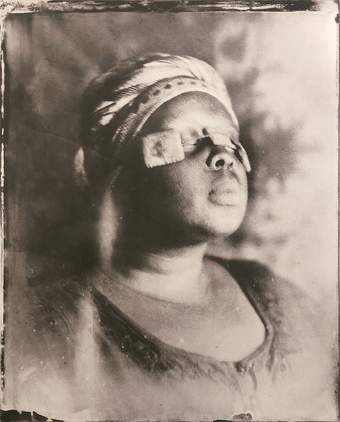

Khadija Saye

Tééré, 2017-8

Silkscreen print on paper

Courtesy of the Estate of Khadija Saye. 2017 by Estate of Khadija Saye. All Rights Reserved. In memory: Khadija Saye Arts at IntoUniversity

In memory of Khadija Saye.

I am looking at three photographs taken by Taslima Akhter in Dhaka after the collapse of a garment factory.

A woman sits outside a fence made of bamboo pillars and wire netting. Because her face is turned away, and her elbows rest on her knees, and her hand holds her head to the side, I know she is watching the rubble of the nine-story building beyond the fence. She considers how the ground is covered in carpets of debris, and how, if she watches long enough, it becomes overcast with gloom. Hence her manner, as she faces both buildings, is telling: a terrible solemnity, as though love is decoupled from life, time and again.

The ruin is brought closer in the next photograph. A lifeless man and woman are trapped within crushed brick, serrated metal and cement. Behind the woman – who I recognise as a woman by the tender grasp of the man – there’s a pink-orange fabric. I cannot tell if this belongs to the woman or another. I cannot tell if the rod pierced through her chest to the ground, or if this is an optical illusion given the angle from which the photograph was taken. As I return to consider the firmness of the man’s grasp, his shut eyes, and the woman’s head hanging backwards in a gasp-like pose, I know this for sure: theirs is a final embrace.

The third photograph is of a woman lying on a bed. Her hands are stretched over the framed photograph of a younger woman. Neither the woman on the bed nor the one in the portrait are in poses that suggest they are recently deceased. My immediate guess is that the woman on the bed mourns the woman in the framed photograph. And my response to this guess is to note the tranquil beauty of the mourned woman – how unchangeably beautiful she has become to those who see her or cradle her image, especially her mother.

The Canadian poet Anne Carson once wrote, ‘If you are writing an elegy begin with the blush.’ I don’t know how to say this without seeming to oversentimentalise the dead. Yet, when we saw her body as it lay in state, we noticed that her face had a blush. I won’t say I am happy when I think of her that way. But I get awfully close to that.