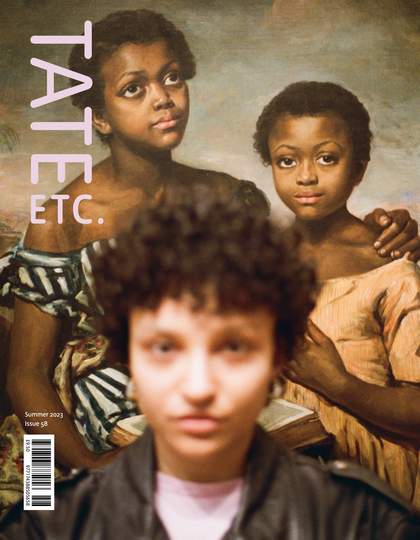

Johan Zoffany

Colonel Blair with his Family and an Indian Child (1786)

Tate

The Indian girl standing slightly behind the English child looks as if she has just come in through the arched doorway, summoned to join the family portrait. The eye is drawn to her, but not only because of the striking red and gold dupatta that covers her head – and mirrors the Colonel’s uniform – or the fact that she is of a darker hue: Where the Blair family are set at a slight angle, their pastel-clad and finely shod limbs arranged in mildly balletic postures, this girl seems unposed, standing heavy on her bare feet. She is clutching a cat that she might have just picked up and looks without guile straight at the viewer.

Is she friends with Maria Blair, the flaxen-haired girl on her right, the two with cat and dog comprising a little family portrait of their own? Of similar age, they may well be friends, but, of course, the Indian child is a servant, likely charged with Maria’s care. The little ayah (meaning ‘nursemaid’ here), dressed in the North Indian Muslim style, does not share the hint of a smile visible on the other faces, leaving her wide-eyed expression open to interpretation. Only the cat glowering directly at the viewer betrays something like displeasure, as felines are wont to at the best of times. Is the cat a mutinous surrogate, freely exuding an unease that Zoffany senses, even if it is not openly evinced on the young ayah’s face?

The animal held somewhat awkwardly in her embrace signifies something of the ayah’s role in the family. Young Indian servants were sometimes described as ‘pets’ and had a status in Britain and British portraiture as ornamental or decorative curiosities. Sometimes literally purchased, they were exotic status symbols for new Nabobs flush with East India Company wealth. They could be a part of the family but were also subject to the vicissitudes of family fortunes and migration. By 1786 in British India, the mixed-race marriages and families of an earlier era were taboo. A young Indian servant could be an alienable item, auctioned to service elsewhere; sometimes sexual servitude might await her. Is there an awareness of this, a sense of uncertainty in the ayah’s body language? Where the family strives to convey a sense of being, literally, at home in India, it is the Indian child who ironically appears to feel ‘out of place’.

Was our ayah brought to England like thousands of other young women from across Asia, sought after as ‘travelling nannies’ and a ‘most valuable adjunct to the whole lifestyle of the Raj’, as historian Rozina Visram describes them? Did she return to India, as some did, or was she left to her own devices, unprovided for and homeless when the family no longer needed her, with no way to pay for her passage back to India? In 1782, the directors ofthe East India Company admonished its employees for leaving many such girls destitute. We can’t know, but I like to imagine that this self-contained girl met with a better destiny after all.

Colonel Blair with his Family and an Indian Ayah was bequeathed by Simon Sainsbury in 2006 and accessioned in 2008.

Priyamvada Gopal is Professor of Postcolonial Studies at the University of Cambridge.

To read more of our special feature celebrating Tate Britain's rehang, visit www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-58-summer-2023/alex-farquharson-tate-britain-the-state-were-in