Derek Jarman

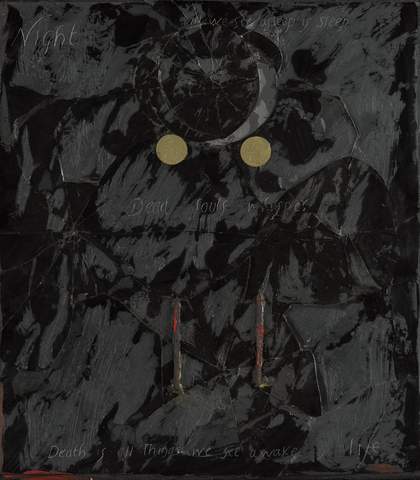

Dead Man’s Eyes (1987)

Tate

This pairing of 1980s assemblage paintings by Derek Jarman connects us with the deepest inspirations of his final decade: courage and fury. Dead Man’s Eyes, created in 1987, bears witness to an almost unbearable moment of loss. This was a year in which it seemed everything was being smashed. In the era before effective treatment, Derek’s recent diagnosis of HIV/AIDS meant that his professional future was in pieces. Meanwhile, as the vindictive amorality of Margaret Thatcher’s government laid waste to everything that Derek valued, his closest friends were dying one by one. Hence the smashed glass; hence the thick, black paint, as if the painting itself was aboutto be tarred and feathered.

This painting is about much more than mourning, however. Two rusted nails from the beach at Dungeness on the English coast are planted in the paint as carefully as Derek was planting the seeds for the garden he was creating at his cottage there; the title almost quotes Ariel’s song of rebirth after a supposed death by drowning in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Most importantly of all, the two gold coins, which focus the painting’s tarry surface, represent the coins that were once placed on the eyes of the dead in payment for their journey across the Styx into the Underworld. An inverted quotation from Heraclitus at the bottom of the canvas (‘Death is all things we see awake’) reminds us of our duty to live both within and beyond mortality. In the darkest moment of a completely secular catastrophe, this painting speaks of grief being alchemised; of smashed fragments storing up hope.

The Clause tackles the same historical moment but in a more combative and sharp-tongued mode. The Clause of the title was Clause 28, a nasty little bit of Conservative Party legislation from 1988 that tried to whip up an extra wave of vote-garnering homophobia by banning ‘the promotion of homosexuality’ in schools. Derek’s cheerfully vulgar riposte captures both the surreal malignancy of that political moment and the outrage and good humour with which LGBTQ+ people and their allies responded to it (the Clause was finally abolished in England in 2003, in response to 15 years of campaigning).

Derek Jarman

The Clause (1988)

Tate

The Clause becomes claws: two monstrous and ham-fisted demons (children’s toys, appropriately) seem to have appointed themselves prison wardens of exactly the sort of queer image that the guardians of the nation wanted Clause 28 to protect our kiddies from. A fragmentary art-school torso is bound up with some more of Derek’s trademark nails, thus evoking the homoerotic cult that he’d so joyously celebrated in his queer art-porn movie Sebastiane (1976). The scratched-in quotation of the then Queen’s own personal motto (‘Evil to him who Evil thinks’) provides the final twist of the image’s polemical knife (perhaps surprisingly, Betty Battenberg – as he called her – was a woman whom Derek much admired, not least for the frigid distaste she always manifested for her arriviste Prime Minister). If you want to see filth in everything, Derek is saying, then shame on you.

Personally, I can’t look at this second picture without wanting to laugh and cry at the same time. In just a few square inches, it summarises a whole decade of my life.

To its blackened partner, my only response is silence.

Dead Man’s Eyes and The Clause were purchased with funds provided by the Nicholas Themans Trust in 2022.

Neil Bartlett is an author and playwright based in London. His most recent novel is Address Book (2021), and his recent work for the theatre includes a West End staging of Virginia Woolf’s Orlando and a live iteration of Derek Jarman’s final film Blue.

To read more of our special feature celebrating Tate Britain's rehang, visit www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-58-summer-2023/alex-farquharson-tate-britain-the-state-were-in