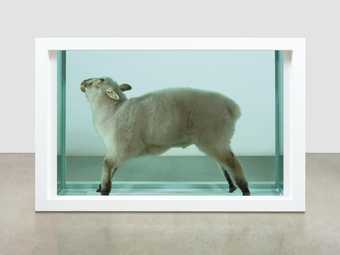

Damien Hirst

Away from the Flock (1994)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

I saw Away from the Flock at the Royal Academy of Arts exhibition Sensation in 1997. I went with my girlfriend Helen (an art student). We’d gone to London for a couple of days.

We had dead sheep on the farm, the same breed as the one in the tank. I knew sheep don’t stand like that, with a curved back; this is how they lay on the ground on their sides when they are dying. I wondered how it died. We used formaldehyde, diluted, for lame sheep, and I was fascinated that someone would use it to try and pause death and decay. Mostly, I was confused how this got to be ‘art’.

Helen asked me what I thought of it. I was reading the blurb thing for the artwork and I said: ‘Have you read this? … It’s just a dead fucking sheep’.

She shrugged this off like I’d crawled out from beneath a stone, on a hillside somewhere culturally backwards, which you might argue I had. No one where I came from really went to ‘modern art’ galleries, except Helen. Damien Hirst was just another pretentious art-school type, and his sheep in formaldehyde was a stunt. I was dead set on hating the whole shebang.

I liked the piece with the rotting carcass and the bluebottles more. I was used to that kind of thing. The look of utter disgust on the faces of the people walking by was special. Oh, and I loved the lifelike rubber model of Ron Mueck’s dead dad, which was hyperrealist, including even his bodily hair. I thought of that piece when my own dad died.

These days, I wonder if Away from the Flock said something important, something I was too dumb to understand. Maybe it was what the 1990s added to our pastoral heritage: a new brutal, visual 3D spectacle, a bit of knacker yard brought into a fancy urban gallery. Maybe it made us look at the ugliness behind industrial food production, and the banal fact that other things die so we can live. Maybe it was about the fragility of life?

Was that what Damien Hirst intended? I’m still not sure. A few years later, I saw bonfires of animals during the foot-and-mouth epidemic – all those legs and noses and bellies swollen or sticking up into the air, against the weirdly green smoke and the flames. I remember looking at our herd of cows on such a pyre, and thinking it was all ‘a bit Damien Hirst’. But the longer I looked, the more I realised it was art – gruesome, epic, horrible, and heartbreaking. This was a never-before-seen spectacle. Our cows, shot and then piled up with a JCB to burn. It had depth and context, as real life tends to – how could art compete with this? The whole gruesome scene should have been assembled in the Tate and set on fire, so people could have seen what I saw. And then I just went home and cried, because it wasn’t art.

Away from the Flock was acquired jointly with the National Galleries of Scotland through The d’Offay Donation with assistance from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the Art Fund in 2008.

James Rebanks is a sheep farmer and author who lives in Cumbria.

To read more of our special feature celebrating Tate Britain's rehang, visit www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-58-summer-2023/alex-farquharson-tate-britain-the-state-were-in