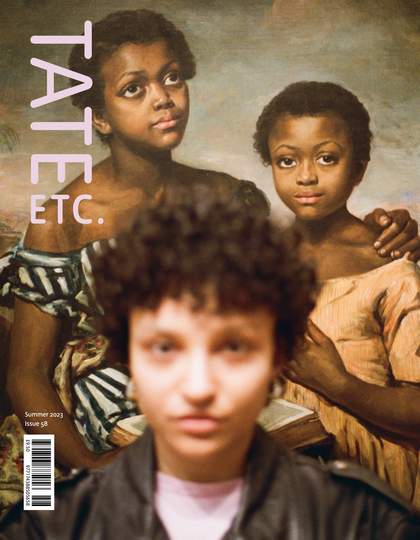

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Fishermen at Sea (exhibited 1796)

Tate

Moon marked and touched by sun*

Those of us who study changes should thank our mothers for losing their minds. I feel so accompanied by the moon. Bask in second-hand light, refracted in relation.

JMW Turner’s mother, Mary Marshall, like generations of my mothers, was diagnosed as mentally ill. And as I have worked to reclaim all my fears, I’ve decided to tell myself the truth. They were/are all artists. They were/are all like me. In the case of my great-grandmother and great-aunt, they were passionate truthtellers, whose truths were so inconvenient to the patriarchs in my lineage that said patriarchs locked them away in a New Jersey asylum. And so, I value my trouble, my freedom. They trouble me to speak the truth.

This is their second-hand light, refracted off the sun as my life.

And so when I look at the moon in JMW Turner’s oil painting, the first he exhibited at the Royal Academy, I think of Mother Mary Marshall, whom Turner’s first biographer describes as ‘a person of ungovernable temper’. Mary Marshall, like my great-grandmother, died in a mental institution. Yes, when I look at Turner’s moon, I think of all the lunatics I love. And where we hide it.

In Fishermen at Sea, isn’t the real painter the moon? Look how she colours the edges of the clouds, tips of the waves. The muted glow illuminating the scene is all thanks to the moon shining full, almost directly above, the weak mockery of light held in the hands of man. Lamplight could pretend to be unrelated to moonlight, but we know. I read Turner’s Fisherman at Sea as a study of power, where the moon and the ocean are in collaboration and men are small and tossed about. So focused and hopeless.

According to a label on the gallery wall, a ‘hard-to-please art critic’ saw this painting as ‘proof of an original mind’. And isn’t an original mind a dangerous possession? My family history has taught me that, yes, it is. My mother, the therapist-in-therapy, my grandmother, co-founder of the Caribbean Mental Health Association, have both taught me that it is a question of what we make out of this cool, changing light and the smaller, more urgent light shaping our faces, burning in our laps.

It can make me feel crazy, my relative helplessness amidst a climate crisis that we are denying so we can burn ourselves to death. What would we do in relationship with this planet – with these oceans that could, at any moment, overtake what man has built – if we acknowledged how small we are, and what exactly is in our hands Maybe we would turn, change, become like Mary: ungovernable.

*from Audre Lorde’s ‘A Woman Speaks’ (1984)

Fishermen at Sea was purchased in 1972.

Alexis Pauline Gumbs is a scholar, poet, activist and educator based in Durham, North Carolina. Her most recent book Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals won the 2022 Whiting Award in Nonfiction.

To read more of our special feature celebrating Tate Britain's rehang, visit www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-58-summer-2023/alex-farquharson-tate-britain-the-state-were-in.