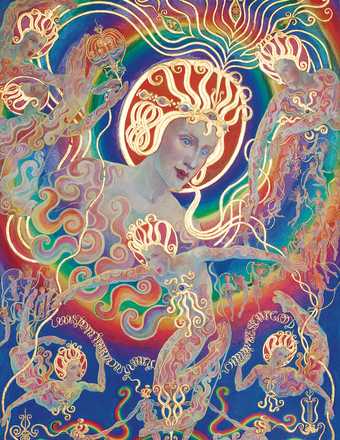

Ethel Le Rossignol, detail of Wisdom, Harmony, Unity, Omnipresent God 1920-33, No 30 of the Goodly Company series of psychic drawings, watercolour and gouache on paper, 72 x 53 cm

Collection of the College of Psychic Studies, London

When I began writing this article I did the usual thing: I opened a new Word file and wrote what I thought might be a good title (it’s still the same one you’re seeing here). Then I left my computer to get a cup of coffee, while pondering a convenient opening line. When I returned to my desk, I noticed something had changed on the screen. Under the title, where earlier there was just an empty page, there was now a sign. It was a zero. Clearly, when I moved away from the desk I must have pushed some papers or a book against the keyboard. But what do I know? Am I sure that it was not my hand that inadvertently touched the 0 key? And if that were the case, should I interpret the 0 as a possible unconscious attempt at writing my text? And would it really matter, from a psychological point of view, to determine what it was that touched the key? No such questions would have come to my mind if it were not that they seemed close enough to the subject of my article, which is the seemingly strange situation of creating a work without having the perception of being its author. In this case, being dispossessed of agency and authorship becomes not an obstacle, but a condition for creation.

The intuitive idea most people have of artistic creation is that artists are able to turn their fantasies and ideas into concrete, perceptible objects by following a more or less elaborate technical process. Whether the artistic establishment will recognise the value of these objects is of course another matter. This is a very rational way of looking at the whole process, a perspective that has been largely predominant in the history of modern art. After all, acknowledging that a particular person is the ultimate ‘author’ of a work implies such a linear view of artistic creation. But the history of Western culture (not to mention those of other cultures) is full of moments in which this simple paradigm has been challenged, whether metaphorically or literally.

After William Blake

The Man Who Taught Blake Painting in his Dreams (counterproof) (after c.1819–20)

Tate

What are we to make, for instance, of the famous series of Visionary Heads that William Blake produced in his late years for the astrologer and artist friend John Varley? The story goes that he drew them as if he were actually seeing them in real life, while Varley was observing him (and seeing nothing). Many of these heads belong to historical figures, such as Julius Caesar, Roger Bacon and John Milton. But one of them seems to be of a different kind, personally closer to Blake. It purports to be the portrait of The Man Who Taught Blake Painting in his Dreams after c1819–20.

For those who are familiar with the ideas of Emanuel Swedenborg and know how important they were for Blake’s own visionary work, there is nothing strange here. Swedenborg’s writings are full of references to spiritual beings who, he claims, taught him about the mysteries of heaven, and it is only logical that Blake would want to receive a similar kind of teaching in relation to his art. Some critics have argued that the artist was not too serious when he was drawing these portraits, and that he just wanted to amuse himself a bit at the expense of Varley’s naivety. Perhaps there may have been a humorous aspect in the situation, but when one is familiar with the rest of Blake’s work one can hardly doubt that he honestly believed in the spiritual power of his imagination. More than that, with this portrait he was prefiguring a model in which not just the content but also the technical side of artistic creation would be outsourced to a different world from the physical one, and to personalities other than one’s own conscious self.

Heinrich Nüsslein, Untitled (Grey Angel) 1930–40s, oil on wood, 50 x 37.6 cm

© Courtesy Sammlung Zander/Collection Zander, photo Alistair Overbruck

Blake’s aesthetic model was far from popular in his own time, at least before Romanticism would open new doors to its appreciation. But in earlier times, at least until the age of the Enlightenment, it had been normal to think that human beings are subjected to all sorts of influences from non-human entities, but also from astral bodies and occult properties of natural objects. This was clearly relevant for artistic creation, as it was common for a poet or an artist to invoke inspiration from the Muses or other divine beings. After all, the very etymology of the word ‘inspiration’ is based on the idea of a person becoming the receptacle of such a subtle, aerial, but nevertheless overpowering presence. Starting from Plato’s Phaedrus, artistic genius has been associated with madness and visionary states, which were supposed to be concomitant with real inspiration from divine entities. With the modern concept of a solidified, monadic self, such a vision of creativity became increasingly problematic and the old tropes of inspiration could survive only as literary metaphors.

Spirit drawing by Victor Hugo, 26 July 1854

© Bibliothèque nationale de France

There is, however, no linear evolution in this story, and what seems to be the modern paradigm of human personality, and therefore also of artistic creation, is constantly questioned and challenged after the Enlightenment. During the 19th century, the doctrines of mesmerism first, and of spiritualism later, offered to these alternative views a theoretical and ideological backbone. Not only improvised artists, but sometimes also well-established ones were attracted by the new theories. Exemplary in this respect is the case of a talented artist such as the French sculptor Théophile Bra. He follows a trajectory that seems to be modelled on that of Swedenborg and prefigures that of Hilma af Klint: after a successful career and a large number of public commissions, Bra goes through a mystical crisis in 1825 and retires to spend the rest of his life in relative isolation, filling thousands of pages with extraordinary drawings and revelations about the spiritual world. If we look at some of his drawings, it is hard not to recognise geometrical patterns that will be seen again later in spiritualist art.

Victorien Sardou, untitled mediumistic ink drawing, c1860, ink on paper, 21 x 14.5 cm

Collection of the College of Psychic Studies, London

In 1848, while Europe was aflame with revolution, upstate New York was seeing the birth of another kind of revolutionary movement. All of a sudden, spirits began to talk. They had been silent for too long, because now they clearly had many things to say. Not just to new prophets or future religious leaders, but to anybody who cared to listen. Political regimes had been shaken and democratised through popular revolutions, and something similar happened to the old regimes of consciousness through spiritualism. It was not just about the thrill of hearing new revelations about the other world. Whether the spirits were real or not, they made it possible for people who did not have a voice suddenly to have one. A method had been found to plumb the depths of human consciousness, and it was suddenly within anybody’s reach. This method led to a widespread outburst of creativity, as the mediums were channelling the literature, music and art that purportedly the spirits did not have the time to create while they were still alive. These works remain today largely a lost continent, in part because of the decline of popularity of spiritualism towards the end of the century, but also because much that was produced in that context was merely either boring or kitsch.

But not all of it was. French literary celebrities such Victor Hugo and Victorien Sardou experimented with spiritualism, and they let the spirits guide their hands in producing mysterious landscapes and fairy palaces. And then we have the almost forgotten gems. When we look at the watercolours that British medium Georgiana Houghton produced between the early 1860s and the late 1870s, for instance, we immediately realise that there is a whole artistic dimension of spiritualism that still deserves our attention. There is something unreal about these drawings, as it is hard to connect them to the period when they were produced. They show a consistent non-figurative pattern, as if they were objects from a reverse time capsule that had been projected back 40 years from the period of the avant-gardes. Like many other mediums, Georgiana practised a form of automatic drawing, working in a state of mild trance and with her hand controlled by her spirit guides. She claimed that even famous artists from the past, such as Titian and Correggio, came from time to time to visit her and help her to produce new works.

Georgiana Houghton, Flower of Catherine Emily Stringer 1866, watercolour on paper, 33 x 24 cm

Collection of the College of Psychic Studies, London

Houghton’s work could be easily compared with that of Hilma af Klint, who began her artistic career in the 1890s. There are interesting differences of course: af Klint had received a more formal artistic training, and she produced many more paintings than Houghton, mostly in larger formats. But for the rest, analogies abound, starting with the most obvious one: they went abstract before abstraction even existed. In recent large exhibitions of af Klint’s paintings it has been easy to present her as a precursor of one of the most important developments in the history of modern art. It would be just as easy to do the same with Houghton. But one wonders whether it is really so important to determine who won the race. What is perhaps more interesting is to determine under which conditions was it possible for Houghton and af Klint to develop a visual language that was obviously so very much at odds with the existing canons of artistic expression. Since agency in the production of the work of art was not claimed by themselves, but was handed over to the spirits, they could afford more radical freedom.

Hilma af Klint, The Dove, No. 4 1915, oil on canvas, 152 x 115.5 cm

Courtesy Foundation of Hilma af Klint

The creative techniques of automatism, based on spirit communication, were formalised by 19th-century spiritualism. Their use did not ensure artistic quality, but they could at least facilitate radical experimentation and innovation. This potential was seen and interpreted positively by early psychologists of the unconscious, such as Frederic WH Myers and Théodore Flournoy. It was the subliminal self that was speaking through the artist, not the spirits, and could express itself in ways that could lead to the development of real artistic genius. The same potential was perceived by the surrealists, who, as in the case of André Masson, were keen to experiment with automatic drawing and other similar techniques. The belief in the spirits had vanished; the new interpretive framework was now wholly secular and based on the insights of psychoanalysis, but the basic techniques were adopted from spiritualism.

Matt Mullican’s Memory Jam: Retrospective Performance Series, Artists Space, 16 May 1985

Courtesy Artists Space, New York

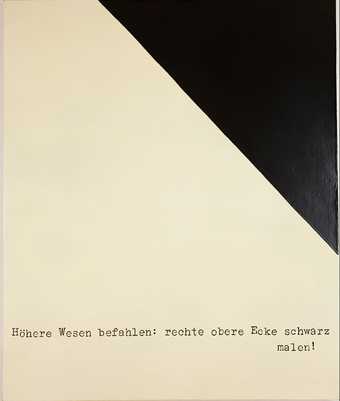

a few contemporary artists have been interested in experimenting with these psychological processes, working with dissociation and alienated agency. Matt Mullican’s odd relationship with ‘That Person’ is as close as postmodern consciousness can get to the experiments of 19th-century mesmerists and spiritualists. In other artists, such as Sigmar Polke with his famous Higher Beings Command: Paint the Upper Right Hand Corner Black! (Höhere Wesen befahlen: rechte obere Ecke schwarz malen!) 1969, we find the same potential ambiguity we had seen in Blake’s Visionary Heads. Is it tongue-in-cheek? Is it serious? Probably a little bit of both. Hardcore spirits have been exorcised with the vacuum cleaner of secular psychology, but what can we do if their invisible hand sometimes still wants to reach out to ours and shake it?