Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings in their studio in London, June 2022, photographed by Angel Li

Photo © Angel Li

Listen to this article

Amy Emmerson Martin What work have you been making for your Art Now exhibition at Tate Britain?

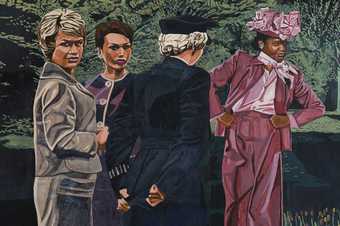

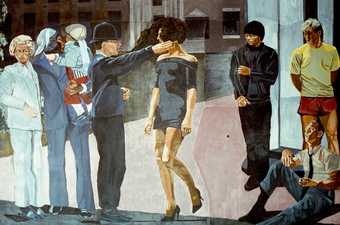

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings We are presenting six new fresco paintings and a large graphite drawing. The paintings depict scenes of exchange, conflict and camaraderie in public spaces – on street corners, down suburban roads, in parks and public gardens. When developing our compositions, we were drawn to ideas such as authority and obedience, questioning the types of authority that exist in public space: legal authority represented by police in uniform, moral authority represented by well-dressed ladies and suited men who observe and perform outrage, and the authority of the street represented by hustlers, loiterers and sex workers who take control of their territory in and around the pavement. The opaque scenarios depicted are imagined in part as an urban territorial battleground between these various forms of authority and in part as the natural surge and swells of people in overpopulated and under-loved cities.

AEM Your practice encompasses video, installation, etching, egg tempera painting, and drawing. Why has fresco felt like the right medium for your recent work?

HQ & RH Fresco painting is often found in places of political, legal and educational importance and is executed at a monumental scale. Traditionally, frescos depict scenes loaded with ideology and symbolism while presenting themselves as neutral or universal. A fresco often represents the moral code of the time within which it is painted, intended as an instructional and educational medium that reinforces dominant perceptions.

Photo © Angel Li

AEM How do you go about making a fresco?

HQ & RH Fresco is the practice of painting with pigment mixed with water onto freshly laid lime plaster, usually on a wall or – as we do it – on wooden panels. It is an obsolete medium, in part because it’s so horribly difficult to execute, due to the speed at which the painting must be executed (while the plaster is wet), and also because of its hideously technical nature. Plaster that is one millimetre too thin won’t absorb the pigment correctly, leaving the surface powdery and chalky. Plaster one millimetre too thick will cause the lime in the plaster to mix with the pigment, leaving a milky bloom on the surface of the painting and hairline cracks as the plaster contracts in the carbonation process. Between these variables are the perfect fresco conditions where pigment, unimpeded by any painting medium other than the carbonated plaster, glows as if illuminated by an inner light. Elusive and very difficult to achieve, this is the part of the process that fascinates and motivates us endlessly. We chase these moments through each very long, physically and mentally draining fresco day.

To prepare for painting the frescos, we make full-scale preparatory drawings called cartoons. We plan each detail down to who will paint what, the colours that we will use and the size of each day’s painting, which is known in the fresco world as a giornata, or a ‘day’. On the day of painting, we apply two layers of silky intonaco plaster – a fatty mix of lime putty and sand aggregate – to specially prepared boards. When the plaster is firm enough to paint, we transfer our cartoon, which has been traced and pricked with thousands of tiny holes, onto it and we dab pigment through the holes onto the plaster to be left with a map of our image to work from. We race to cover all the white plaster with a watery layer of paint, which seasons the plaster and helps keep it moist for more detailed work.

Photo © Angel Li

AEM How have you learnt to work in this tricky medium?

HQ & RH We are largely self-taught. In 2020, we did a one-week course with Fleur Kelly, an experienced fresco painter based in the south of France, where we learnt the essentials. But the only true way to learn to paint fresco is through experience and the development of a symbiotic understanding of the materials and their characteristics.

We work to keep the painting style bold, graphic and monumental, since fresco is not a subtle medium. In certain areas, such as faces, we work more intensively, building up layers of pigment until we are able to blend on the surface of the fresco. In other areas, we use only a single layer of paint. When we paint, we don’t sit down or talk or change the music. We are so anxious about the plaster drying before we can finish the image that we work in a state of heightened focus. When it works, it feels transcendental; when it doesn’t, it feels like hell.

The nature of painting in giornata, or section by section, is a highly unusual way to approach a painting because with other mediums such as oil paint, the painting is typically built up as a whole in layers. The surface of the fresco has scars running through it where the plaster joins; the small changes between colour mixes day-to-day can create a completely different feeling from piece to piece. There is naturally a degree of uncertainty as the painting changes so radically in the drying process. We decided to embrace this aspect of fresco painting, to heighten rather than disguise its sculptural qualities. We love how visible the process is on the surface of the painting – how the fresco has its own architecture, and how the plaster and pigment turn to rock that will last forever.

AEM The architectural qualities of built environments also feature prominently in your recent paintings, as they do in a lot of your work. Why is this something you keep returning to?

HQ & RH Exterior and interior architecture has always played an important role in our work, from our first collaborative project @gaybar, when we built fully functional gay bars in studios and galleries and hosted live event series, to UK Gay Bar Directory, a moving image archive of gay bars in the UK. We are interested in architecture as something that shapes people’s behaviours, desires and orientations. For some, domestic architecture represents power – each property owner is the king of their castle – and for others, it represents repression and is a space encoded with rigid ideas of gender roles and sexual behaviour.

Photo © Angel Li

AEM Have you drawn on specific artistic influences when creating your new works?

HQ & RH Our fresco series is heavily influenced by the Masaccio, Masolino and Filippino Lippi fresco cycles in the Brancacci Chapel in the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence, Italy. The frescos in the Brancacci Chapel depict biblical stories of saints who raise the dead, heal the sick, aid the poor and suffer imprisonment. These saints move through the palazzi and public spaces with a sense of authority and social standing; they are often depicted as stern and powerful – prosperously clothed among a sea of rags and standing upright among the sick, dying and poverty stricken. We are interested in the way that these religious stories unfold within public spaces, where we witness an unruly clash of registers: the disciplinary power of the state versus the political and communal charge of the streets.

Meanwhile, the graphite drawing is roughly based on Paolo Uccello’s painting The Battle of San Romano c.1438–40 in the National Gallery in London, a battle scene featuring soldiers in armour and many horses. In our drawing, the battle scene becomes one of police militarisation, featuring mounted police in full riot gear. We have been thinking about the militarisation of the police in light of the new Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill and a ‘tough on crime’ political approach that results in urban gentrification, sweeping police powers and an expanding carceral system.

Photo © Angel Li

AEM Have you been looking beyond art history too when carrying out research for these paintings?

HQ & RH For these frescos, we worked heavily with archival street photography from London, Paris, Berlin, New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. We sifted through hundreds of images during our research and cut up sections of photographs that we then used to make collages for our compositions. Certain characters depicted in the frescos are Frankenstein’s monsters, assembled from many different gender expressions, body parts and costumes. Working with street photography archives – some dating back to the advent of photography – we were able to make our own history of the street, with the freedom to play with an infinite number of potential interactions between the figures. The result is that each painting speaks of many eras, expressed through architecture and costume. Working with existing archives or creating our own has always played a significant role in our practice. We are interested in creating an emotional and sensual relationship between the viewer and a historical moment. We are also interested in a horizontal rather than hierarchical relationship to history, and building empathy and understanding across generational divisions.

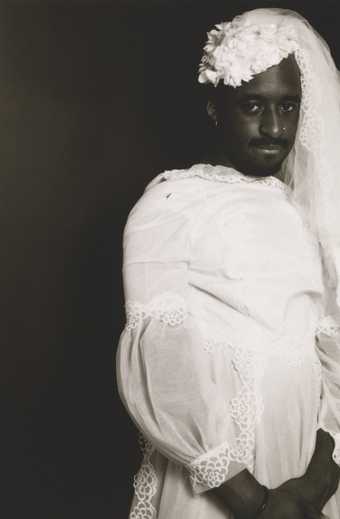

Working with archives also allowed us to make historical interventions and revisions. For example, one of the fresco paintings draws from images of two pairs of drag queens being arrested from gay bars in New York in the 1950s. In the 1950s and 1960s in the United States, the ‘three-article rule’ was used to criminalise LGBTQ+ people, especially so-called ‘cross dressers’. The rule stipulated that each individual must be wearing at least three articles of clothing assigned to their biological gender at any given time and resulted in a huge number of arrests in gay areas, such as Greenwich Village in New York, where police raids were frequent and brutal. In our fresco, we removed the offending police officers and the handcuffs from the arms of the drag queens, transforming the scene into one where the queens are walking home from a wild night down a leafy suburban street. Interventions in art-making can’t heal the past or absolve it of its violations and abuses, but it can help you to reimagine the future, especially when drag performers, trans and non-binary people continue to shoulder the burden of such disproportionate political vitriol.

Photo © Angel Li

AEM How long have you been working together in this way?

HQ & RH We have worked together for eight years. At first, we argued constantly as our individual artistic egos battled for space and our attitudes towards making clashed. Now we have a way of working that allows us both to flourish. On a good day, we have a deep understanding of our own vulnerabilities and strengths, we help each other grow, and we surprise each other constantly.

When we work, we are often very quiet. We tend not to talk very much in the studio and, strangely, our work creates distance between us as we disappear into deep tides of concentration. When we develop new ideas for work, the conversations are a spark of shared excitement that we can both visualise unfolding into a full body of work. We delegate roles to one another in research and development and we tend to have meetings outside the studio where things feel less loaded and difficult. Occasionally, things spiral out of control, we lose faith in what we are doing, have crazy fights and find it impossible to work.

In order to work harmoniously, we follow a regimented approach to producing work and managing our studio. In relation to the frescos, we have a series of rules that apply to creating the composition, drawing the cartoon and finally painting. We design each giornata so that there is enough for us both to paint each day. People consider our way of working, especially on drawings or paintings, highly unusual, as they think about painting within the context of modernism and the myth of the artist as an individual genius. We think about art-making within a broader historical context as early practices of art-making were highly communal. Large groups of artisans would work together under the control of a master to produce works: one artisan would specialise in painting flowers, while another would paint the architecture. We work like artisans, but we have no master.

Photo © Angel Li

AEM Speaking of flowers, where did the title of your new show come from?

HQ & RH We struggled to find a title for this exhibition as we didn’t want to privilege one aspect of the narrative or define the viewer’s experience of the work. In the end we settled on Tulips, which refers to the foliage that runs through all the work in the exhibition. In public spaces, tulips exercise a form of control over green spaces where what is grown or not grown is tightly managed. This form of urban planning is reminiscent of the ‘broken windows theory’ in criminology, where visible signs of crime and disorder are seen to incite further anti-social behaviour and civil disorder. If broken windows signal disorder, tulips signal order. We see this desire for control and order in dialogue with notions of the commons, and the cultural and natural resources available to all members of society. In the urban scenes of the fresco paintings, the commons would ideally represent the streets and the public garden. These spaces, however, are subject to increasing surveillance, policing and privatisation, prescribing who uses these spaces and how. We think of Sylvia Plath’s description of the flowers in her poem ‘Tulips’:

Their redness talks to my wound, it corresponds.

They are subtle: they seem to float, though they

weigh me down

Despite the weight of tulips, the promise of the commons perseveres, like beautiful weeds growing in the cracks.

Hannah Quinlan & Rosie Hastings live and work in London.

Amy Emmerson Martin is Assistant Curator, Contemporary British Art, Tate Britain.

Audio narration by Radhika Aggarwal and Wesley Nzinga.