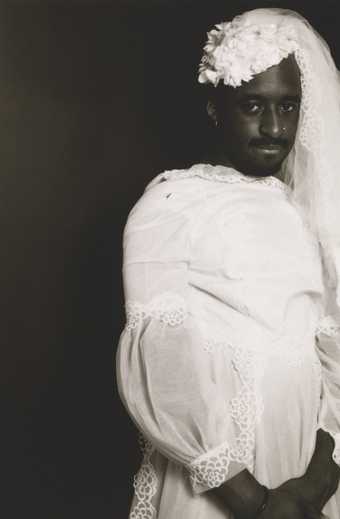

Ajamu

Self-portrait in Wedding Dress 1 1993

Gelatin silver print on paper

7.3 × 4.9 cm

© Ajamu

MELS EVERS You process your photographs in your own darkroom. Why is that important?

AJAMU A lot of the conversations around Black and Brown and queer photography aren’t about process, craft, making and aesthetics – they get pulled into content and representation instead. Somehow we expect the art to do some political or educational work. So, for me, the darkroom is a way to stay connected with a history of photography. The darkroom is also about touch, materiality, texture and sensation. In the darkroom I am bodily.

ME How does this relate to scale? Some of your prints feel very small and intimate.

A In a lot of my early nineties work, the scale drew on these small business cards used by sex workers in phone boxes. They were normally three inches by two inches. With erotic work, a small image brings a curiosity and pulls the viewer towards it, creating this intimate moment, a one-to-one encounter where one wants to look and doesn’t want to look at the same time.

ME Who or what else has influenced you?

A Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Jo Spence, Cindy Sherman, Pierre Molinier, pornography. I would even say music – Soft Cell’s Non-Stop Erotic Cabaret, that album was my backdrop as a young lad living in a small town. Some influences are drawn from my own sexual encounters. And paintings – surrealism plays a part in the work as well. So I steal, lovingly, from lots of places.

ME Can you say any more about working with photographers across generations?

A As a young photographer, it was great to have someone to look at your work and to ask them: what do you think? Rotimi did that for me. I came across his portfolio in Gay Times in October 1987, and through him, I joined the Brixton Artists Collective. I would go over to his house and show him my work. At that point, he was the most visible, out, Black, queer photographer. That’s something I try and do now: my house is a hub for younger Black, queer photographers – some who I’m mentoring informally.

ME Tate are releasing a limited edition print from your Circus Master 1997 series. Why did you choose to revisit this work?

A Parents should never have a favourite child, but Circus Master is probably my favourite series. It captured something I was thinking about deeply around S&M and kink, and the model at the time was a boyfriend of mine. I like that the images are very gentle, and historically I don’t see many images of Black men like that. For those of us who are out about being into kink, what is missing is a conversation around intimacy and gentleness within something that might appear quite violent and aggressive.

Self-portrait in Wedding Dress 1 was presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest in 2021 and is included in the display 60 Years at Tate Britain, from 13 October.

A limited edition print from Ajamu’s Circus Master series is available to buy on Tate’s website from 24 September.

Ajamu talked to Mels Evers, Assistant Curator of Displays, Tate Britain.