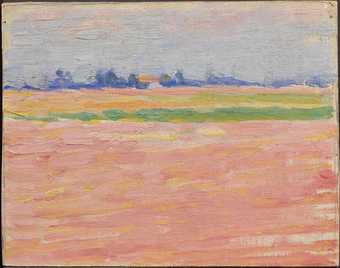

Walter Sickert The Blackbird of Paradise c.1896–8. Oil paint on canvas. Leeds Museums and Galleries, UK / Bridgeman Images

Walter Sickert (1860–1942) is known by many as the father of modern British art. Active in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, he was described as ‘one of the most gifted painters to have worked in this country since the days of Turner’. He is credited as having introduced impressionism and post-impressionism to a generation of artists working in Britain, shaping the course of art in the UK. Even now, Sickert continues to have a profound impact on contemporary painters.

Sickert was born in Munich in 1860, and at the age of eight moved with his family to Britain. Following a short career on the stage, he briefly studied at the Slade School of Fine Art in London before choosing to pursue art in 1882, becoming an apprentice to James Abbott McNeill Whistler, the renowned American artist who was living in London. Influenced by Whistler and French impressionist painters, particularly Edgar Degas, Sickert developed his own innovative approach to subject matter, creating radical painted compositions that evoked the materiality of existence.

Sickert first became well-known for his realist paintings of rowdy music halls, which catapulted his career to new heights. Travelling frequently between Venice, Dieppe, Paris and London, he painted scenes from his travels, all the while developing a series of penetrating self-portraits. His imagination was also fuelled by news and current events such as the Camden Town Murder, a brutal murder of a woman by an unknown assailant, which caused a sensation in the press. In the later years of his career, Sickert became absorbed in using small black and white newspaper photographs as a basis for large and colourful compositions, an artistic innovation that can be viewed as a precursor to the pop art movement.

Walter Sickert, c.1930s

Islington Local History Centre

Sickert was a founding member of the postimpressionist Camden Town Group, active from 1911 to 1913, and his contemporaries frequently gathered at his north London studio, inspired by his enthusiasm to paint everyday urban life. Not interested in showing a veneer of society, Sickert instead showed life’s gritty realities – painting scenes of dank interiors or dreary streets in London and abroad. His depiction of ‘gross material facts’ inspired many British artists of the 20th century, including Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud.

In the articles that follow, six contemporary painters share how Sickert has influenced their art, a testament to how relevant the artist remains to this day.

Thomas Kennedy is Assistant Curator of Modern British Art at Tate Britain.

Kaye Donachie on Sickert’s portraits that tell a story

Walter Sickert

Mrs Swinton 1905–6

Oil paint on canvas

Leeds Museums and Galleries, UK / Bridgeman Images

Virginia Woolf, in her essay ‘Walter Sickert: A Conversation’ (1934), recalls a fellow dinner guest’s comment about Sickert’s paintings: ‘When he paints a portrait I read a life.’ Woolf, thinking through the implications of this comment, had more sympathy for the idea that ‘Sickert always seems more of a novelist than a biographer … He likes to set his characters in motion’.

This way of reading a painting interests me – of allowing narrative impulses to emerge from inventive painterly descriptions. Sickert honed his vocabulary through preliminary sketches as structure, building the pace with tonal marks towards the final scene. The image emerges through expressive impasto daubs and strokes, evoking its subject and stories.

Mrs Swinton 1906 boldly depicts Mrs George Swinton, Elizabeth Ebsworth, a prominent Edwardian society figure. Mrs Swinton was a regular sitter for Sickert and other artists of the time. A brief career as a professional singer and performer was curtailed by family pressures, followed by charity work and investment in esoteric philosophies. The face is mask-like, the profile three-quarter, eyes fixed and partially glazed, perhaps preoccupied by people or events off set, elsewhere in the studio. The sitter, melodramatically, is both a projection and a reflection of affect, her sharp, glass-like expression a mirror to us all.

Curiously, Sickert places his subject against a Venetian setting, a city Mrs Swinton had never visited. This fictionalised composition is a particularly interesting fabrication. The landscape amplifies the artifice of the theatrical backdrop for the fictionalised performer. The muted green tones of the water peek through parts of her red dress and body, as if the scene were a film still caught midway in a cinematic dissolve. The figure and the background are painted with the same intensity, compressing the image into one moment of time.

The genre of portraiture fills museum and gallery walls, creating shadows of protagonists who weave time, history and power through a cast of the represented and the unrepresented. Sickert’s portraits plot points of interest as he manages to go beyond the academic. For me, he is a painter who constructs ideas forged through his stylistic choices. I read Sickert’s portraiture as a coat hanger on which he confers actors, framed through recollection and emotional connection, conjured in the act of painting. The gaps of unpainted canvas, created by scumbled brush marks dragged across a surface, articulate forms that seem to fade towards the edges of the frame and can be read as spaces or openings for subjective elucidation.

I enjoy the sense of theatricality in his portraits and the technical lens-like adjustments which pull into sharp focus the faces emerging from the grubby, blurred grounds. Sickert’s experiments with painting show a changing visual world. He seeks to capture the electric atmosphere of early cinema; his paintings contend with the theatre of images, seemingly predicting the cultural significance of montage and assemblage.

Sickert’s haptic melodramas attempt to move away from the literal descriptions of specific sitters ‘setting his characters in motion’. Painting, instead, moves towards figuring a fiction, forming characters who are invented and evolve through painterly and compositional decisions.

If we consider Sickert a novelist, as Woolf did, then his fiction remains deliberately fragmented, leaving a narrative that is always present and continually reimagined. His portraits are stories constructed and captured within multiple time frames, making them as vital now as they were historically. He allows us to consider the portrait as a timely screen – an imaginative, playful stage onto which we have permission to continually re-enact our own emotive scripts.

Kaye Donachie is an artist who lives and works in London.

Somaya Critchlow on Sickert’s reframing of the nude

Walter Sickert

The Studio: The Painting of a Nude 1906

Oil paint on canvas

Private Collection. Image courtesy of PIANO NOBILE Robert Travers (Works of Art) Ltd

Walter Sickert’s painting The Studio: The Painting of a Nude 1906, part of his Camden Town Nudes series, has a nude figure as its central focus. She has become a staged duplicate of multiples, sandwiched between the reflections of a mirror on either side. It is a scene in which we, the viewer, bear witness to the artifice and staging of image-making. But we are not alone as viewers: in the foreground, cutting across the woman’s body, is the arm of a man, that of the painter and observer, Sickert himself. He is controlling the viewpoint of the audience, just as he is controlling the positioning and portrayal of his model.

While Sickert’s intentions initially seem clear – to reframe and reposition the nude – the paintings themselves plague the viewer with their unnerving psychological tension; a tension that plays with viewership, the history of the nude, and the acceptable subjects of painting.

In Sickert’s 1910 essay ‘The naked and the Nude’, he wrote that modern representations of nudity had become so vacuous that they could not be considered anything but degrading. The nude in the 1900s had become synonymous with the female figure in art, as a vision of perfection idealised to the highest aesthetic. In contrast, Sickert’s Camden Town Nudes allow nakedness to operate outside the confines of the nude. They are paintings that depict women and sex workers in run-down apartments, amongst cheap furnishings, and leaning against or lying on iron bedsteads.

The subject matter is controversial, perhaps like my own depictions of the Black female body. Sickert’s paintings of women explore anti-academic poses and the composition of woman as subject/ object. They are at times bleak and contain traces of violence, particularly in the group of four Camden Town Murder paintings, in which a clothed male figure is introduced. These paintings are challenging and innovative, appealing to a darker, more carnal human intrigue and curiosity. The sombre images take their place among those such as Édouard Manet’s Le Suicidé (The Suicide) c.1877, or the grim depiction of rape in Intérieur (Interior) 1869–9, also known as Le Viol (The Rape), by Sickert’s predecessor, Edgar Degas.

At a dinner hosted by Virginia Woolf, she and her guests discussed Sickert’s ‘silent land’, a capacity of ‘seeing things that we cannot see, just as a dog bristles and whines in a dark lane when nothing is visible to the human eyes.’ It is true that there is something poetic and moody in Sickert’s work which you can’t put your finger on, an abstraction of life that investigates its darker side. The ‘silent-land’ is the creation of things that can be felt without being seen, an experience that seems familiar while being intangible. Sickert’s The Studio reminds us of the familiarity inherent to nakedness by dispelling the idealisation of the nude, but further unsettles us by situating it in an explicit façade – the act of painting, a construction of art.

Somaya Critchlow is an artist who lives and works in London.

Merlin James on Sickert and photography

Walter Sickert

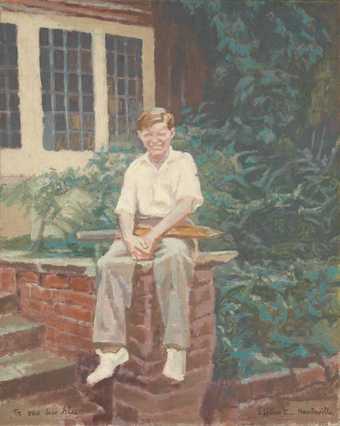

Claude Phillip Martin 1935

Oil paint on canvas

Photo © Tate

Sickert is about entity and identity – what it is to be somebody, or anybody. Among his many works in Tate’s collection, the portrait Claude Phillip Martin 1935 doesn’t make it into the present exhibition, maybe partly because the sitter is unknown. He’s named in the title, but if you Google him, all that comes up is this picture. He’s just a kid, whose three first names only make him seem all the more anonymous.

He’s evidently been copied from a family-albumtype snapshot. The cropping, scale and placement of the figure in the frame appear unconsidered, and Sickert doesn’t try to improve them. In fact, as much as painting the boy from the photo, he paints the photo of the boy. Effects we might disregard in the snapshot itself, or be only partly conscious of, are pointed up. There’s the coincidence of the window mullion rising from the boy’s head. There’s the lens’s slight enlargement of the legs and feet, diminishing the head and shoulders. The figure seems to hang in space over a wobbly foreground void. Colour and tone are rather greyed-out, as can happen when a photo features a bright area like the sunlit shirt here. In such conditions, the camera ‘squints’, just as the boy is squinting back at us, into the light. Edges are blurred and details are lost. Look closely and the boy’s eyes are not really there at all; the effect is a little disturbing. Still, he is surely grinning. Cricket bat across his lap and maybe a ball cupped in his hands, he’s happy enough in the moment.

But that instantaneity of the camera’s shutter (people often caught blinking) is another thing Sickert renders. He paints the frozen moment and the attention it draws, paradoxically, to the resumed continuum of time thereafter. What became of that boy after appearing in this image? I’m reminded of Chardin’s solitary youths with their playthings – house of cards, spinning top – intimations of future fates and fortunes.

In the catalogue for the great 1992–3 Sickert exhibition held at the Royal Academy in London and the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, the art historian Richard Shone pointed to the ‘pictorial tension’ created by the area of blue-green foliage in Claude Phillip Martin. It’s not just pictorial. The longer one looks at this dark, camouflage-like mass encroaching on the figure, the more disturbing it is. Its churning density seems almost to conjure up grotesque faces. One becomes aware of how close a grin can be to a grimace, cheerfulness to tearfulness. Perhaps the picture presages tragedy.

Of course, paintings don’t make predictions, except in that if they tell profound enough truths, those truths will go on being borne out by events, one way or another. One work included indispensably in the new exhibition is Miss Earhart’s Arrival 1932. Sickert transcribes a newspaper photo this time and the subject is a celebrity. Ace pilot Amelia Earhart has just completed her transatlantic solo flight. Yet she’s almost entirely lost amid the jostle of waiting crowds, lashing rain and bobbing umbrellas. When we finally spot Amelia’s tiny profile, she’s not addressing or even acknowledging journalists or fans. She still has the inwardness, the intent satisfaction and self-sufficiency of her recent isolation in the cockpit, in the clouds. There’s no real air of arrival (unlike with Sickert’s full-length monarchs and magnates, striding to meet us). Instead, Earhart, pictorially still one with the body of her aircraft, appears to be continuing on her own determined trajectory. Five years later, attempting a circumnavigation of the globe by plane, she vanished. Search parties and investigations continue to this day, attempting to find her. I think she’s there in Sickert’s painting.

Merlin James is an artist living and working in Glasgow.

Louise Giovanelli on Sickert’s use of mass media images

Walter Sickert

Juliet and Her Nurse c.1935–6

Oil paint on canvas

Leeds Museums and Galleries, UK / Bridgeman Images

Sickert’s use of appropriated and reimagined photographic sources, particularly in his later work, is familiar territory to me. I often employ a similar cropping device when making a painting – a ‘zooming in’ on areas of images I find most interesting. This allows me to reconfigure and reappraise. I am effectively using painting as a camera, drawing attention to details that would otherwise be overlooked, left unexplored or dismissed.

In the same way, Sickert takes images circulating in the world and studies and observes them. Isolated from their original context, these images appear as fragments of a narrative. There is an erasure and undoing of prior meaning, leaving interpretive room for the viewer. This dance between the painted mark and photographic source would play out in the work of painters for the rest of the 20th century, and we are seeing its effects acutely now, with the recent influx of figurative painters who, like myself, work with found imagery.

For me, the image is only one move of many. It is the starting point, the launch pad, from which painting must take over. Like a baton passed in a relay race, painting speeds away, necessarily, from the source image. The photograph is the smoking gun. Something has been signalled, impressed – and from there the journey of painting begins.

There is a difference between making a picture and making a painting. The distinction is subtle but important. One is a document and the other an experience. Sickert made paintings. We can see that, for him, the newsprint excerpts and found images functioned as a preliminary aid, a starting point from which to build. What is often discussed in relation to Sickert’s late works are the narratives behind the images – their sources, dates of publication and other historical details – but what we should be looking at instead is how Sickert deals with problems of painting. Formal considerations, such as how to arrange shape and colour, the consistency of the paint, surface quality, translucency, opacity – this tacit knowledge is what the artist is foregrounding and where meaning resides.

It is the low-resolution nature of newsprint and photographs found in the mass media – their lack of clarity and definition – that I believe Sickert was fundamentally interested in. Again, I see connections with my own work, as I also seek low-resolution starting points: film stills from a particular era, with a grainy, flattened, colour-saturated surface, such as The Birds (1963) and Carrie (1976), were the starting points for my recent small portraits Cameo 2020 and Auto-da-fé 2021.

That he was exploring these ideas in the 1930s shows just how radical Sickert was for his time. It is as if he is showing us that painting doesn’t have to, and maybe shouldn’t ever, fully illustrate an idea or narrative; that photographs should lead, should suggest, but never tell.

In Juliet and Her Nurse c.1935–6 (one of my favourite Sickert paintings), the incorporation of low-resolution and chance effects from the photographic source opens up space for painterly effects. The approach is tonal as opposed to linear, with large expanses of colour dryly scrubbed into the canvas weave, leaving gaps of raw material that glitter and dissolve. It is through the gaps that the meaning resides. All of this is light and surface. All of this is a painting, not a picture.

Louise Giovanelli is an artist based in Manchester.

Matthew Krishanu on Sickert’s ability to paint an inner life

Walter Sickert

La Hollandaise c.1906

Oil paint on canvas

Photo © Tate

Two prints of Sickert’s paintings are taped to my studio wall: La Hollandaise c.1906 and Portrait of an Afghan Gentleman c.1895.

In La Hollandaise, a woman is shown partially reclining on a bed. The figure is contained within the curves of the iron bedstead, her shoulder and hip echoing its lines. Like all Sickert’s paintings, the work is, for me, primarily about the paint itself – the calligraphic certainty of its marks, the beauty of the light catching form out of shadow, and the atmosphere of greens, pinks, creams and greys.

I first saw the painting hung alone at Tate Britain and was drawn in. Years later, in 2007, I saw it alongside other paintings from Sickert’s group of Camden Town Nudes in an exhibition at the Courtauld Gallery, where it seemed set in a world together with its companions. I love how constructed these paintings are; they are painted from pencil sketches and then invested with atmosphere and form in the artist’s studio, away from the scene. They are like places and people remembered and imagined.

Walter Sickert

Portrait of an Afghan Gentleman c.1895

Oil paint on canvas

© Jerwood Collection / Bridgeman Images

In 2015, while visiting the Jerwood Collection in Hastings for the first time, I met Sickert’s Portrait of an Afghan Gentleman and was halted, struck by how present the man seems. Judging by the attention and formal interest that Sickert invested in the painting, it was surely painted from life. I love the wisps of the man’s moustache and beard, the curls at the back of his neck; the gradations of red-brown, greenish brown and cream in the skin tones, and the powerful, textured brushstrokes that form his white collar. I am taken by the interiority of the gaze – the man has an inner life, a sense of purpose. By contrast, La Hollandaise is more constrained by her circumstances – boxed in by the bed, bare and somewhat downcast, but to me still possessing a sense of dignity, even monumentality. Not just their figures, but so much of their lives, their worlds, are created in the paintings.

I keep returning to these two images when in my studio. When feeling my way around the face of one of the ‘two boys’ who recur in many of my paintings, I think of the Afghan man’s cheekbones. And when creating a bed in a room (whether in a domestic setting or in a hospital), I feel once again the weight of Sickert’s mattress and his iron bedframe.

Matthew Krishanu is an artist based in London.

Andrew Cranston on Sickert’s nocturnal palette

Walter Sickert

Minnie Cunningham at the Old Bedford 1892

Oil paint on canvas

Photo © Tate

Walter Sickert is one of those painters whose work I’ve absorbed over a long time. Everywhere I’ve lived since the age of 20 (I’m now 52) – Manchester, Aberdeen, London and Glasgow – has had a wonderful Sickert or two in its museums. Through reproduction, too, I have had him with me in the studio: a postcard of his music hall painting Minnie Cunningham at the Old Bedford 1892 is pinned to my studio wall.

Sickert is one of the great image-makers and one of painting’s most distinctive colourists. I think of him, especially in his early work, as a sort of psychological impressionist with a feeling for the dark rather than the light – an inverted Claude Monet, and yet so much more than ‘just an eye’, as Monet was once described by Paul Cézanne. Sickert’s nocturnal, close-toned palette acknowledges the eye’s ability to adjust to low light, and to discern shape, forms and figures in the peripheral and hidden.

Minnie Cunningham at the Old Bedford locks the eye in with a crepuscular closeness of tone. The central slab of red pulses and glows in the context of those muted, foggy brownish greens. It is a reverberating musical painting whose abstract properties – its proportions, its chromatic values – are the visual equivalent to music, an innate, self-enclosed condition to which ‘all art constantly aspires’, as the critic Walter Pater wrote in 1873. Of course, ironically, paintings are silent.

This painting has the subtle nuances of observation but with the mysterious, haunting quality of a memory or dream. I wonder if the film director Nicolas Roeg knew this painting when he made Don’t Look Now (1973). More inexplicably, it’s always reminded me of the moment in Star Wars (1977) when Princess Leia first appears as a wavering hologram. There and not there, Sickert’s performer is painted side-on. We are allowed to look without our gaze being returned; we take in the scene unnoticed, from the dark.

The head is interesting and becomes a focus, not through greater description but more due to the lack of it – a passage of un-painting, where it looks as if Sickert has taken paint off rather than put it on, perhaps achieved through blotting with absorbent paper, or ‘tonking’, as it’s known to painters.

I simply love gazing at that red and am warmed by its flame. I couldn’t tell you what colour of red it is exactly, but it reminds me of meeting the painter Craigie Aitchison when I was a young painter. I had made a large red-orange painting for an open competition and he, as one of the judges, had awarded it first prize. At the opening he charged up to me and asked impatiently, ‘Where did you get it? The paint for your painting? It’s vermilion scarlet, isn’t it? I can’t find it anywhere.’ And then, as if addressing the room of mainly businessmen: ‘That bloody Thatcher banned it!’

Andrew Cranston is an artist who lives and works in Glasgow.

Walter Sickert, Tate Britain, 28 April – 18 September 2022. Curated by Emma Chambers, Curator, Modern British Art, with Thomas Kennedy, Assistant Curator, Modern British Art, Tate Britain. Supported by Tate Patrons and Tate Members.