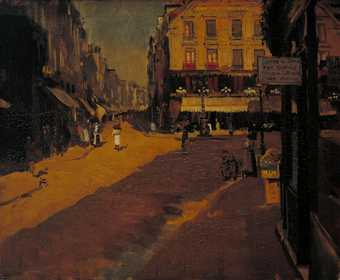

I like Sickert's The Old Bedford: Cupid in the Gallery c.1890 best. The mooning faces, young and old, of the men in the cheaper seats of the Old Bedford music hall peer out of a perspectival labyrinth of mirrors and plasterwork at the punters drifting through Tate Britain's 'Degas, Sickert and Toulouse-Lautrec' exhibition. No audience imagines itself watched. Sickert has caught us all with our guards down.

An hour later, I am unpacking large brown cardboard boxes to scrutinise the Sickert-related objects which chance has carried to the archive at Tate Britain. His painting overalls are here: two pairs of high-waisted trousers, a shirt and a buttoned jacket, all in ivory-coloured Egyptian cotton, faintly splodged with blue, black and yellow paint stains. "His palette is a poor wretch in faded rags," wrote the art critic Monod of Sickert. These are well-pressed rags. The painter's latterday inquisitors have sniffed over them hoping for DNA evidence that he was Jack the Ripper (no matter that Sickert was in France at the time of most of the murders). Alas, the overalls were steam-cleaned before donation.

From a fantastic case to a real one: leather-covered, hinged, fastened by a long brass pin and lined with purple silk. A nickel-plated instrument lies within. A clamp is joined by a telescopic rod to an array of adjustable arms, the last holding a tiny glass prism with a frame in front of it. One of a dozen small, rectangular glass lenses nested in silk-lined slots is intended, I assume, for the frame. A small piece of paper with a handwritten legend explains the enigmatic contents.

"This Camera Lucida belonged to Walter Sickert, lent to me and, alas - Kept! Enid Bagnold, when I was perhaps 24."

A camera lucida is used to transfer an image from life on to paper. Clamped to a drawing board or table, the rod holds the prism at a precise position and angle between the scene in front and the paper below. Looking down through one of the glass lenses, the eye sees the image on the plane of the paper and thus can simply trace it off.

In practice the instrument demands great skill. The eye cannot vary its distance from the glass by more than the diameter of its pupil, which is about 2/10 of an inch. David Hockney recently proposed a camera lucida as the means behind the uncanny draughtsmanship of Ingres, although it was invented after the artist's death, and Hockney's own experiments with it are unconvincing.

This camera lucida would have been borrowed around 1912. Enid Bagnold, the later author of National Velvet, attended various of Sickert's classes from 1909 onwards. The artist learned of the belief that Canaletto had used a camera lucida to compose some of his views of Venice, when he visited that city in 1895, and could recall it almost 40 years later. Might this one have afforded him a similarly useful technical shortcut?

The only evidence would be negative: a lack of preparatory sketches for a complex work. Sickert's music hall scenes present formidable perspectival challenges, but the thought of him setting up his apparatus amidst the patrons of Gatti's or the Old Bedford is an improbable one. The light was too weak anyway.

It seems likely that this beautiful, rather impractical instrument was acquired, toyed with, then happily discarded. Its presence here in the archive tells us that Sickert owned a camera lucida. Also that, after lending it to Enid Bagnold, he never asked for it back.