Portrait of Danielle Dean

Courtesy Danielle Dean

NATHAN LADD The video installation you’re working on for your exhibition at Tate Britain originates from your research in the Ford Motor Company archives in Detroit, particularly your discovery of a plantation in Brazil called Fordlandia. Could you tell us about that?

DANIELLE DEAN Fordlandia was a work camp for a rubber plantation set up by the industrialist Henry Ford in the Amazon rainforest in 1928. He wanted to control every aspect of the production of Ford cars, even the raw material used for tyres. Using the Ford logic, he planted Indonesian rubber tree seeds close together, but nature doesn’t always like rational, profit-yielding organisations. In fact, you shouldn’t plant rubber trees close together because it creates disease. It was a complete failure, and Fordlandia is now just a ruin.

NL What sort of material were you coming across?

DD As well as the Ford Motor Company archives, I also visited the personal archive of someone who collects Ford adverts. All the early drawings got me thinking about the American dream – of buying a car, particularly a Ford, and how that relates to a history of representing the landscape as something that you can consume from the comfort of your own car.

Fordlandia Dance Hall, Boa Vista, Brazil, c.1933

From the collections of The Henry Ford

NL Did you learn anything about what it was like to live and work in Fordlandia?

DD Ford described Fordlandia as a ‘work utopia’. He wanted to cultivate the ideal worker – not only ensuring that they worked efficiently, but that they also lived a moralistic way of life. He saw things like jazz as corrupting, so he promoted square dancing, because it was more ordered and ‘civilised’. It’s so regimented that you’re like: ‘Oh OK, is that to do with the assembly line?’

NL As part of your project, you’ve been looking at a parallel Amazon, the e-commerce company, and specifically its Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT) platform. Could you explain what that is?

DD AMT is a crowd-sourcing platform made up of ‘workers’ and ‘requesters’. Requesters can be big corporations, entrepreneurs, professors in a university – anyone who wants access to lots of people, and to gather lots of data. The workers fill in surveys about their emotions, or identify something in an image that feeds AI technology. It’s human labour on a mass scale, and all of this work is about generating data for algorithms. Back when Fordlandia existed, in the 1930s, rubber was a big deal, but now data is big business. There’s a comparison to be made between the history of a raw material that comes from nature, and the mining of immaterial labour under capitalism today.

Ford Country Sedan advertisement, 1959

From the collections of The Henry Ford

NL What will people see when they walk into your new work, Amazon?

DD They will see a large projection of a landscape that represents Fordlandia. It has a bit of a Disney feel, because it’s influenced by Ford car commercials, which have that feeling too. Then, monitors are positioned around the space, each telling the narrative with the AMT workers. They’re filmed in their homes, and they have props which connect them to the projections of the rainforest.

NL What did you learn through making this comparison across history?

DD Thinking through the history of how labour is changing also brought up the discussion of political dissent. There was a riot at Fordlandia because the workers were unhappy with the reality of Ford’s utopian dream. I had conversations with some of the AMT workers about the fact that it’s very hard to have a union when everyone is working on their own at home. How do you have a revolt when you’re not together?

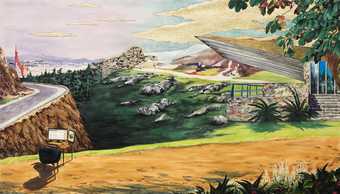

Danielle Dean

4. a.m. 2021

Watercolour on paper

126 × 213 cm

© Danielle Dean. Courtesy the artist and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson

NL It’s interesting that, even outside of a Fordist factory, there may be built-in structures of power that control you as a worker in your own home, working on your own computer.

DD AMT work is itself a form of surveillance. You have to do exactly what is asked for at a certain time, and if you don’t do what they call a ‘HIT’, or a ‘human intelligence task’, in the way you are requested to do it, you don’t get paid. It’s almost harking back to medieval times, because if you’re a salaried worker, and you do something wrong, your employers are not going to say you’re not getting paid today.

NL It feels slightly Orwellian, or Black Mirror-esque...

DD But it’s real! With the work I make, reality is way more fucked up than fiction.

Art Now: Danielle Dean, Tate Britain, 21 January – 8 May 2022. Curated by Nathan Ladd, Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art, Tate Britain. Art Now is supported by the Art Now Supporters Circle and Tate Americas Foundation.

Danielle Dean is an artist who lives in Los Angeles.