George Frederic Watts

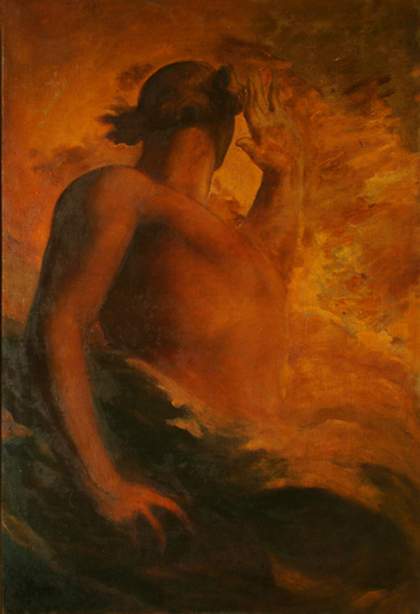

The Dweller in the Innermost (c.1885–6)

Tate

George Frederic Watts’s great, flawed project was to paint the story of humanity, from creation to the immutable qualities of life and of death. This vast series, The House of Life – conceived around 1848 but never completed, seems yet more implausible today: how could one person capture the world’s many voices and truths? What Watts did realise were fragments of this vision – works that distil his understanding of the spirit and the cosmos through an intuitive, economic symbolism. These ‘symbolical’ paintings, as the artist termed them, formed part of a broader development in European art – one that began with romanticism in the late 18th century and was later reinterpreted by symbolism and surrealism.

Rejecting a rigid rationalist worldview – which divided body and soul, dark and light, and flattened the universe into a mechanistic order – these movements embraced the chaos of existence. Symbolism, which flourished from the 1880s to the 1910s, was loosely affiliated and wide-ranging. It encompassed work that evoked the spiritual, the quintessence behind the material world. Though Watts was rarely in conversation with these artists, working in relative isolation and drawing inspiration, rather, from the practice of Dante Gabriel Rossetti or William Blake, he exhibited his paintings internationally and had a significant impact on the movement.

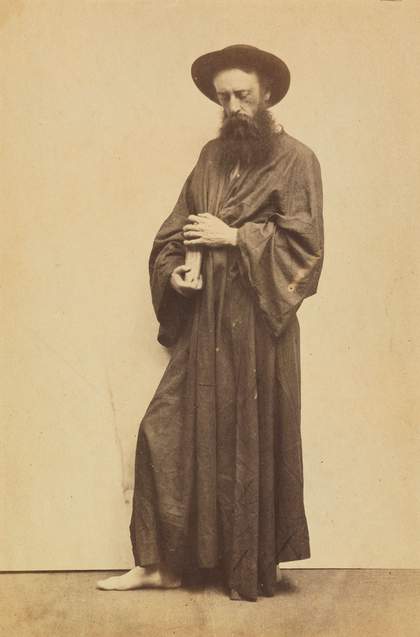

George Frederic Watts, photographed by James Soame, c.1854–8

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Works such as Love and Life c.1884–5 illustrate Watts’s appeal to a Victorian audience, whose agnosticism was marked by a deep yearning for spirituality. By the late 19th century, Christianity had lost its authoritative standing, its mythos rethought even within its own factions. With the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) and new geological findings, humankind and the Earth were reappraised from the vantage of evolution and a history that preceded the Book of Genesis by millennia.

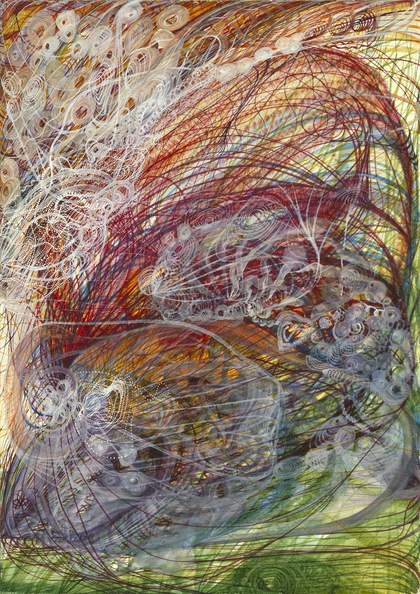

George Frederic Watts

Love and Life (c.1884–5)

Tate

Numerous esoteric organisations were founded, or gained popularity, during this time, including Theosophy, Gnosticism, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and the Society for Psychical Research, of which Watts was a member. In this context, Watts’s image of Life – frail and trusting, held up and guided forward by Love, ‘with his wide wings of sympathy, charity, tenderness and human affection’ (as the artist wrote in On Taste in Dress, 1883) – suggested another compass by which to live, one both lofty and immediate.

Chaos c.1875–82 also revisits our foundations. It imagines the formlessness from which the elements took shape, drawing on the creation myths of ancient Greece and evolutionary theory. Here, a pale figure rises from a tide, reflecting the idea that life first emerged from the sea. Its stretched limbs and bulging back suggest a struggle into being, while heavy Titans form part of the mountain on the right. A chain of dancing, leaping figures soars between them, signalling the boundless passage of time.

Herein lies the key to Watts’s distinct symbolism: it relies on the knowledge that our bodies already hold. His works unlock a primal notion – that the human body rhymes with both a flower and the cosmos, and the most intuitive gestures echo a greater whole. In Sic Transit 1891–2, for instance, the iconography of the vanitas (a genre underlining the transience of life and worldly attributes) lies below a dead and shrouded figure: the ermine robes of state, a lute and book for the arts, a gilded shield for vainglorious wars. Yet it is the foot, stone-like and still, that conveys the gulf and finality of death: the point at which a sheet becomes a shroud and the material world falls away.

Hope 1886 looks not to absence but to ‘the indestructible minimum of the spirit’, as G.K.Chesterton described it in 1904. It depicts a woman with bandaged eyes, who sits on a globe amongst the clouds. She bends her ear to a lyre, listening for the music of its one unbroken string. Her long neck twists and dips down, leaving soft flesh exposed, and it is this gesture – in such a melancholy image – which embodies the vulnerability that we must embrace to have hope. Over more than a century, this painting has inspired many – from suffragette Olive Hockin to civil-rights activist Martin Luther King, Jr. and former president Barack Obama. This recognition is at the core of Watts’s work, for while we live our joys and struggles in the space of years or days, they echo across the ages, fragments of a whole.

A selection of paintings by George Frederic Watts is on display as part of George Frederic Watts: Poems on Canvas, Tate Britain, until September. Curated by Caroline Corbeau-Parsons, Curator, British Art 1850–1915, Tate.

Caroline Marciniak is a writer and Editorial Coordinator of Frieze who lives in London.