What is there in absinthe that makes it a separate cult? Even in ruin and in degradation it remains a thing apart: its victims wear a ghastly aureole all their own, and in their peculiar hell yet gloat with a sinister perversion of pride that they are not as other men

Aleister Crowley, The Green Goddess (1918).

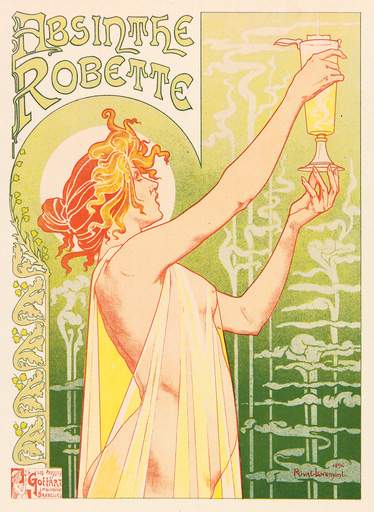

T. Privat Livemont

Poster for Absinthe Robette 1896

© David Nathan-Maister & The Virtual Absinthe Museum

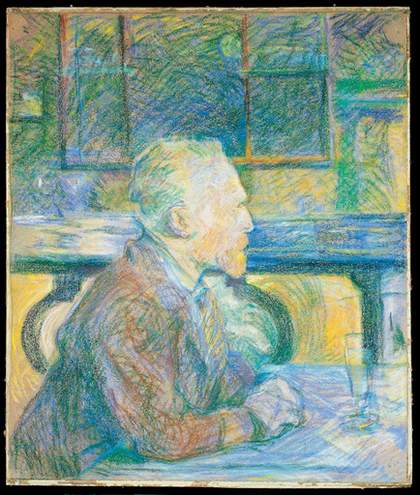

In the second half of the nineteenth century absinthe became commonly known as “the queen of poisons” and in France was considered responsible for a range of social changes – from an increase in numbers incarcerated in asylums, to trade union unrest and even women’s emancipation. It also became a symbol and a fuel for a caravan of creative individuals who made the nation a centre of artistic life, and artists including Toulouse-Lautrec, Picasso, Gauguin, Van Gogh and Degas either drank it or made it the subject of their paintings.

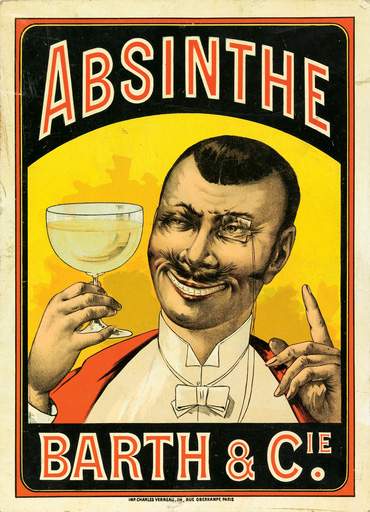

Advertising sign for Absinthe Barth & Cie

© David Nathan-Maister & The Virtual Absinthe Museum

Absinthe had been known of since biblical times; indeed, the name seems to have come from the Greek absinthion, meaning undrinkable. It was made from wormwood leaves and sometimes had an alcohol content as high as 80 per cent by volume. The modern absinthe story began in the 1830s when French troops fighting in Algeria used it as an anti-malarial, mixing it with wine to make it more palatable. They brought their newfound taste for the bitter drink home with them, and it soon became popular, particularly among the Parisian middle class who wanted to align themselves with the prestige of their soldiers.

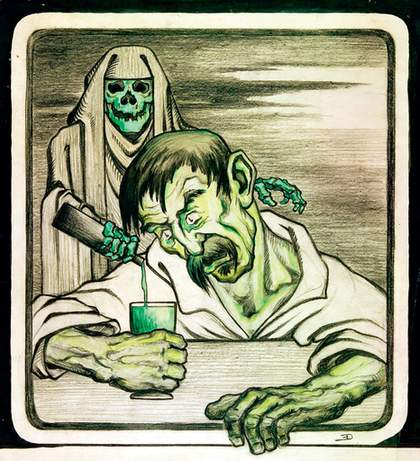

Emile Decoeur

Untitled c.1910

© David Nathan-Maister & The Virtual Absinthe Museum

“The Green Hour”, as it came to be known, saw Parisians filling the boulevards, moving from one café to the next. The turn-of-the-century writer H.P. Hugh recorded:”The sickly odour of absinthe lies heavily in the air. The absinthe hour of the Boulevards begins vaguely at half-past five… but the deadly opal drink lasts longer than anything else.” With the devastation of vineyards in the 1870s caused by the insect phylloxera, the wine still being produced was too costly for the poor. This helped to pave the way for absinthe to become a drink for the people; it could now be made cheaply with the use of industrial alcohol. Soon street corner vendors were producing massive quantities for sale at just a few centimes a glass.

Its appeal coincided with a time when artists living in Paris were exploring alternative subject matter to the accepted genre painting. The poet and critic Charles Baudelaire, in particular, was developing theories about the relationship between art and life.”The painter, the true painter,” he wrote in 1845, “will be he who can extract from present-day life its epic quality.” One of Baudelaire’s friends, the young Édouard Manet, had just left the studio of Thomas Couture in 1858 and was determined to create a style that he could reconcile with the world around him. In 1859 he painted a drunken ragpicker called Collardet with a broken absinthe bottle at his feet. (The rather incongruous glass of absinthe on the wall next to the man was added at a later date.) When Manet showed The Absinthe Drinker to his teacher, he was disgusted. “It is you who are the absinthe drinker,”Couture told his pupil, “it is you who have lost your moral faculty.” Not surprisingly, when Manet entered the painting forthe Salon of 1859 it was rejected.”Insults are pouring down on me as thick as hail,” he told Baudelaire. This did not deter the avant-garde artists from creating absinthe-related pictures. The Belgian Félicien Rops was preoccupied with drawing women absinthe drinkers around the dance halls of Paris. He completed Buveuse d’Absinthe in 1865 and repeatedly painted different models in the same pose for the next 30 years. In reference to one that he produced in 1876, he wrote: “It is a girl called Marie Joliet who arrives every evening drunk at the Ball Bullier and who sees with eyes of electric death.” The young Picasso painted several haunting images featuring absinthe drinkers, such as Woman Drinking Absinthe 1901, The Absinthe Drinker 1901 and Two Woman Seated in A Bar 1902.

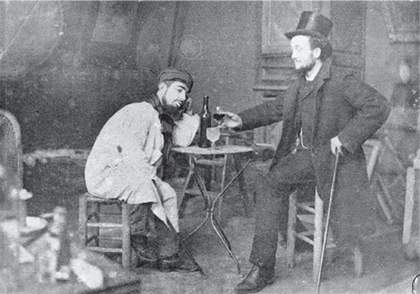

Toulouse-Lautrec and Lucién Metivet drinking absinthe c.1885

Photograph

© Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, Albi-Tarn, France

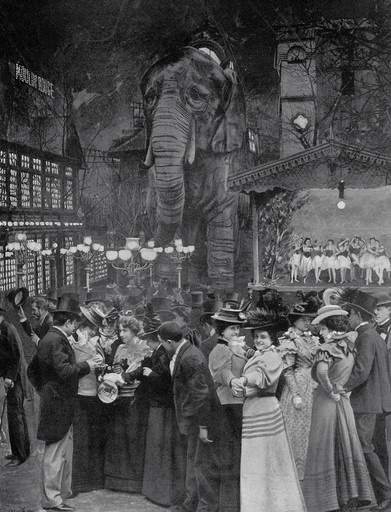

While most of these artists remained relatively passive flâneurs and only occasional absinthe drinkers, some immersed themselves in the experience. An official report later remarked that many late nineteenth-century Parisian writers and painters gave themselves up to “the green” with passion in their quest for more original and exquisite ideas. Among the most prominent of these was Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who illustrated the life of the music halls, the bars, the brothels and, in particular, the Moulin Rouge. The disabled aristocrat famously carried a hollow walking stick which contained a draught of absinthe, and was occasionally accompanied by a pet cormorant that he had trained to drink it. He liked to experiment by adding ingredients. One concoction was the Maiden Blush, a composition of absinthe, bitters, red wine and champagne. Another, created for the legendary dancer Yvette Guilbert, was the tremblement de terre, made from absinthe and cognac. His lifestyle inevitably influenced his work. The symbolist painter Gustave Moreau commented that Lautrec’s paintings “are entirely painted in absinthe”. Even the colour of the drink may have had an effect on Lautrec, who commented that he felt haunted by colours: “To me, in the colour green, there is something like the temptation of the devil.”

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Portrait of Vincent van Gogh 1887

© Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam/Vincent Van Gogh Foundation

French art and attitudes found favour with a marginal group of English bohemians who adopted absinthe along with other habits from across the Channel. One was the poet Ernest Dowson, who assumed the mantle of his French hero, the Symbolist poet Paul Verlaine (also a fan of absinthe). He led a short life (1867–1900) of verse, tragic love and family suicide, and wrote Absinthia Taetra, a tortured dedication to the drink. A contemporary quoted the poet as saying: “Whiskey and beer are for fools; absinthe for poets; absinthe has the power of the magicians; it can wipe out or renew the past, and annul or foretell the future.” The English painter Charles Conder also drank it to excess, and in one remarkable image made it the subject of a dreamlike sketch. A friend noted how he “worked by fits and starts, his life punctuated by love affairs and too much absinthe”.

Attempts were also made to duplicate the ambiance of the French café in the Café Royal in Piccadilly, as seen in such paintings as Sidney Starr’s At the Café Royal and William Orpen’s The Café Royal 1912. Though it was frequented by British artists such as Walter Sickert and William Rothenstein, the Europhile American James Whistler and Oscar Wilde, it was a diluted version of French culture rather than a natural expression of indigenous avant-garde life, and was not embraced by much of London society.

In fact, the English resistance to all things French – particularly the “French poison”– was strong. In Marie Corelli’s 1890 novel Wormwood: A Drama of Paris, one of her characters comments:”There are, no doubt, many causes for the wretchedly low standard of moral responsibility and fine feeling displayed by Parisians of today – but I do not hesitate to say that one of those causes is undoubtedly the reckless Absinthemania, which pervades all classes, rich and poor alike.”

The sentiment would crystallise over Degas’ L’Absinthe 1875–6. He had posed two of his acquaintances, Marcellin Desboutin, a painter and etcher, and Ellen Andrée, an actress, sitting at a table in front of a black coffee and an absinthe respectively. Ellen has a blank expression – staring ahead in an absinthe reverie. The painting (originally called Dans un Café) was first exhibited in the second Impressionist exhibition in 1876 and was bought by Brighton-based collector Henry Hill. He displayed it under the title A Sketch at a French Café, though with little reaction. However, when it came up for auction at Christie’s in 1892 (now known as Au Café ), the lot was hissed at by the crowds and eventually sold for a mere £180. When the Grafton Gallery showed the canvas again in 1893, it deliberately aligned the work with the green drink by entitling it L’Absinthe for the first time. The response from the press was intense. It was lambasted by the more conservative art critics as immoral, vulgar, boozy, sottish, loathsome, revolting, ugly, degraded and repulsive in its depiction of “humanity besotted by drink”. The picture did, however, have its admirers. D.S. MacColl, art critic of the Spectator (and future keeper of Tate from 1906 to 1911), called it “the inexhaustible picture, the one that draws you back, and back again”.

At the turn of the twentieth century much of France (and parts of the rest of Europe and the USA) was on an absinthe binge, but the perceived social costs led to an attempt at its prohibition. Backed by the wine growers, the temperance movement targeted absinthe as responsible for alcoholism, racial degeneration and social instability. Numerous attempts were made to curb its production and consumption. Despite that, 1913 was a bumper year with a record 5.25 million gallons being consumed. At the outbreak of the First World War, the drink was seen as a threat to the nation, and in late 1914 Finance Minister Ribot told the National Assembly that to vote for the bill to ban absinthe was an act of national defence. Armed with the belief that it was causing mass desertion among troops, it was finally banned in France in 1915. In what could be seen as an act of artistic defiance and a bohemian’s farewell to the green fairy, Picasso made his famous Cubist bronze, Absinthe Glass, and individually painted six casts of it.

Nineteenth-century Photo Relief of the Garden of the Moulin Rouge 1898

© Mary Evans Picture Library

Since then, absinthe has made a quiet, if restrained, comeback. In keeping with the fascination with the drink as a cultural phenomenon, Marie-Claude Delahaye opened an absinthe museum in 1994 in Auvers-sur-Oise (where you can see Toulouse-Lautrec’s absinthe spoon). In 1997 the musician John Moore, of the Jesus and Mary Chain, wrote about the drink in The Idler magazine, after trying it following a performance in Prague. He introduced it to the magazine’s editors, who subsequently set up a company to import it. While absinthe was once a symbol of decadence and temptation, it has since become a source of entertainment. In From Hell (2001), Johnny Depp plays Inspector Abberline, trying to capture Jack the Ripper while in an absinthe-induced haze, and in Baz Luhrmann’s film Moulin Rouge (2001), Kylie Minogue plays a cute green fairy.

Artists and poets painted and wrote about their experiences among themselves. Now the internet provides a wider audience for those who wish to share their thoughts, and it is clear that absinthe continues to hold an attraction. However, not everyone is favourable. On one site called The Vaults of Erowid, a college student wrote:”My roommate had explained that people from America’s past had raved about this drug until it was outlawed, so I decided the trip must be somewhat enjoyable. However, I was wrong. This stuff tasted like liquid dog shit. I could barely drink a two ounce bottle without gagging uncontrollably.”