When the 22-year-old Charles Conder arrived in Paris he discovered his spiritual home. English by birth, he had spent his youth in the Australian bush on trigonometrical expeditions, joined up with Australia's first group of plein-air painters and produced an astonishing and precocious collection of Impressionist landscapes. But the attraction of Europe was soon irresistible, and once in the French capital he wrote back to his Australian painting companion Tom Roberts: "The jabber of my friends, the click of the billiards and the smell of heliotrope all belong so much to this café... I have just looked over the Moulin and persuaded my friends to go there for an hour and met their curses the next morning."

The bohemian milieu was Conder's natural habitat and he soon befriended Louis Anquetin and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who would invite him not merely to brothels and nightclubs, but occasionally to executions by guillotine and also sometimes as a spectator at surgical operations (one of Lautrec's preferred amusements). His imagination fired, Conder would describe his exotic adventures in letters to Australia to be read with envy and incredulity by his "squarer" chums around a bush campfire beneath the Southern Cross.

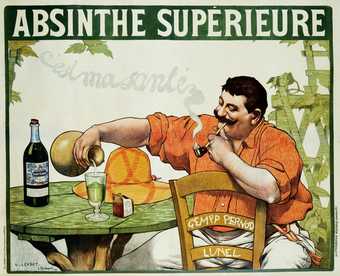

Conder frequently drew "postcards" illustrating his nocturnal adventures in the Latin quarter in an imaginative composite. A Dream in Absinthe 1890 is one such pictorial diary; a fantasia in comic strip form in which he parades the imagery of his new metropolitan life in the City of Light, 13,000 miles from the tall eucalypts, the lavender blue hills and the golden beaches of Australia. His early gift for linear improvisation is evident here, and among the alcoholic demons and opium poppies he has interspersed glimpses of the Moulin Rouge, La Gouloue and Lautrec himself. The picture is drawn in a manner which is half oriental and half influenced by the caprices of Parisian artists of the demi-monde such as Adolphe Willette, but also with a nod to Conder's old friend from his Sydney days, Phil May, who was soon to join him and the young William Rothenstein in their ramshackle studio on the rue Ravignan. Here and there the iconography is obscure – what are all those poultry doing? And is it a strangled peacock in the foreground? The picture is not so much symbolic, in the mode of the time, but anecdotal, and is clearly done for the amusement of the artist's friends. It is also, of course, a pictorial hallucination inspired by that dangerous verdant liquor which was to the taste of Conder and his friends what patchouli was to the napes and décolletages of their mistresses. Is the green-haired figure in the revealing kimono fastened with a chatelaine the Spirit of Absinthe herself? And why the prosaic jar of cold cream and the bottle of dentifrice? Perhaps these are just the first objects Conder saw when, with a pounding post-Absinthian hangover, he opened one eye in the morning wondering where the hell he was. It is a whimsical and wonderfully vagrant invention and rather modern as well – the sort of thing one might expect from someone like Cy Twombly, if he could draw.