Titian

The Rape of Europa 1559–62

oil paint on canvas

© Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

I’m having strange dreams. A man is tortured over 24 hours, somehow like a clock. He bears it stoically, looks at his broken hand. It’s the night the lockdown is announced. Early the next morning, a friend trapped in Hong Kong sends me a photograph on Messenger of a collage he’s been making. It’s very beautiful, composed of strips of gold and dun-coloured paper, stippled with black. There’s one small blue region, like an evening sky over a quiet sea. At the centre, the black takes over and there are shadowy crowds of people, and the eerie orange glow of a vast fire.

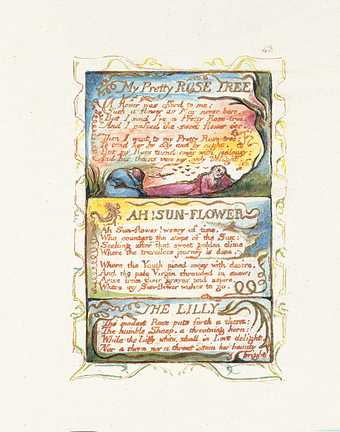

The colours put me in mind of William Blake. I find it strangely soothing right now to look at Blake’s muscular and shining human bodies, racked by forces they cannot understand. ‘Robert’, for instance, an illustration from his epic poem Milton (c1804–11). The figure is bent backwards beneath an almighty sky, skin so reddened it appears flayed, a comet smashing to Earth right by his feet. At the moment we’re all bombarded by bad portents, trying to dowse out what the future will be. We’re all reduced to the bare fact of our bodies, a vulnerability that centuries of human ingenuity designed to mitigate or transcend, if not obviate entirely.

Olivia Laing holds open a copy of Misericords: Medieval Life in English Woodcarving (1954)

Courtesy Olivia Laing

The week before the lockdown started, as galleries and museums began to shut their doors, an image kept cropping up on Instagram of Titian’s The Rape of Europa 1559–62, brought from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston to the National Gallery and displayed for two days before the museum closed. Titian painted Europa at the moment of being abducted, flung off her feet by a great white bull, Zeus in disguise. The saddest thing about the scene is the sight of her fat, dimpled thighs, waving in the air, cellulite exposed for all to see. It’s her total, abject helplessness that I connect with right now: the feeling, conveyed by way of painted flesh, that this wasn’t supposed to happen, is outside the plan – that spectrum of possibilities and likelihoods within which each one of us was operating, and which has now been so spectacularly upended.

Art loves to linger on that moment when disaster afflicts one person, while the rest of the world continues on its daily round. This was WH Auden’s observation in his famous poem ‘Musée des Beaux Arts’ (1938), itself about Pieter Bruegel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus c1588, another painting that situates a catastrophe within an otherwise imperturbable world. But the odd thing about the current crisis is that we’re all Europa, tumbled and terrified, swept towards an unknown destination, long past the point of no return. No painting in history is going to change that, but I don’t think looking is a hopeless act. Art has enormous powers of its own, not least its capacity to arrest or collapse time.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus c1558

oil paint on canvas

Bridgeman Images / Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels

I don’t feel like a citizen of the 21st century at the moment, for all that I’m typing on a MacBook. I feel medieval, and it comforts me to look at medieval art. Not so long ago, but in a very different world, my husband gave me a 1954 King Penguin book called Misericords: Medieval Life in English Woodcarving. I’d barely glanced at it, but this week I’ve been gripped. Six, seven, eight hundred years ago, craftsmen across the country were carving misericords on the underside of tip-up seats in churches, jutting corbels that monks could surreptitiously rest a portion of their weight on while forced to stand for lengthy sessions of prayer. These corbels were decorated with all manner of religious and domestic scenes, grotesque beasts, mermen, elephants, arks, shepherds, knights, tapsters, boat-builders, green men, griffins, football players, owls and hen-pecked husbands.

The one I’m looking at now is a Rogationtide figure from Worcester. It shows a small oaken man with bandy legs and a beard, his jacket emblazoned with heraldic button roses. In each of his hands he holds a great bough, the branches just taller than him and exploding with flowers at either end. Rogationtide, from the Latin to ask, is a spring festival of the Christian Church dating back to the seventh century, in which parishioners entreated God to bless their crops and begged for protection against calamity (it survives today as the beating of the bounds). If I wasn’t in lockdown, I’d be tempted to drive over to Worcester and lay down an entreaty of my own. Since I can’t, I must content myself by gazing at this hopeful figure with his armfuls of blossom, embodying the most ancient of pleas: Let there be enough food. Deliver us from evil. Give us what we need.

William Blake

‘My Pretty Rose Tree’, ‘Ah! Sun-Flower’ and ‘The Lilly’ from Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1794)

hand-coloured relief etching on paper

Photo © Tate

We’ve been insulated from the urgency of those prayers for a very long time. Now, calculating food stores and worrying over far-off family members, it’s as if the medieval imagination has re opened. In those days, most people lived on the edge of disaster, one poor harvest or broken leg away from absolute catastrophe. The things they made might have been designed to ward off bad luck or usher in fertility, but they’re also testament to the desire, in hard times as well as good, to make something lovely or strange, to copy the world’s abundance or to invent a wayward new form: a hart eating a snake, perhaps, or two naked women fleeing from a dragon.

Paul Nash

Eclipse of the Sunflower 1945

oil paint on canvas

Courtesy of the British Council Collection, photo © The British Council

Art has always been made in times of crisis, one eye on the door and the other on the gods. It has always been a way of bribing fate – here, take what I made – and also a technology for relishing right now. In the grim final year of her diary, 1941, Virginia Woolf wrote that the phrase ‘look your last on all things lovely’ kept ricocheting though her mind. The war had begun. There were bombing raids and rationing. She was often hungry, often afraid. Her diary records a London in ruins, the air thick with smoke and brick dust from burning houses and bombed squares: ‘all that completeness ravished and demolished.’ In the growing darkness, lovely things seemed almost to scald the eye, gaining a hallucinogenic clarity.

It’s the same mood of magnified strangeness you find in Paul Nash’s final paintings: the apocalyptic fever dreams of giant flowers falling from the sky. He made Eclipse of the Sunflower in the last year of the war, 1945, a year before his own death of pneumonia. It’s inspired by a Blake poem and painted in an illuminated Blakean palette. A giant, golden floral wheel rolls through an inky, fretful sky, coloured in weird swathes of violet and brown, above the wreckage of a sunflower plant, its dead leaves crisped and dry. How would you analyse this portent? It’s disquieting to look at, and yet it plainly enacts the same ongoing, eternal cycle as the Rogationtide figure from Worcester, the seasonal round of plenitude and death. Nash was reading James Frazer’s The Golden Bough (1890), pondering fertility myths as he struggled to breathe.

It’s a frightening painting, I think, and at the same time it’s hard to look away from. The eye is inexorably drawn to the bright light emanating from behind the sunflower’s furry brown eclipse. More is going on here than we can see. Where is it headed, that wheeling, fertile form? What new life can it possibly usher in?

Olivia Laing’s latest book is Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency, published by Picador.