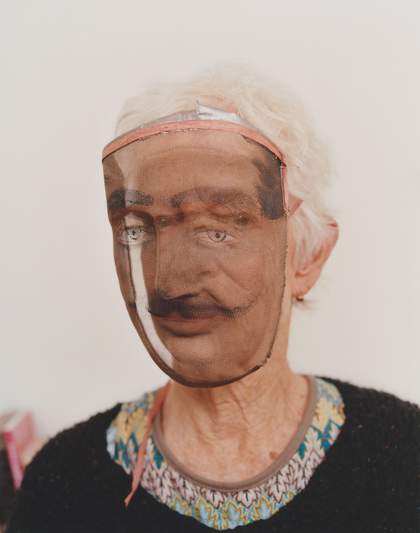

Natalia Goncharova with 'Basic makeup for an actress of the Futurist theatre', published in Teatr v karrikaturakh, 21 September 1913

State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, photo: Andrei Sarabianov

It has taken a long time for many women artists to gain the recognition that they deserve, but to some extent, Natalia Goncharova (1881 –1962) is the exception. She was one of the first women artists to become a leading avant-garde figure, acknowledged as such by her innovative male colleagues. Together with her partner Mikhail Larionov she dominated the Russian art scene of the first half of the 1910s, spearheading the creative developments that underpinned the heroic Russian avant-garde’s achievements: challenging the establishment, defying pictorial conventions, and producing powerful and innovative works that continue to delight and astonish.

Her output was prodigious. In 1913, she showed over 800 works at her solo exhibition – the first public, one-woman show in Russia – held in both Moscow and St Petersburg. The futurist poet Ilia Zdanevich published a monograph about her and Larionov – probably the first book to analyse and chronicle the work of a woman artist. She was a prominent member of the innovative Jack of Diamonds group (also known as the Knave of Diamonds) and, in true avant-garde spirit, she pushed the boundaries of acceptability in subject matter, style and ideas, extending this into the arena of public behaviour.

Born into an impoverished aristocratic family she identified with figures on the fringes of society, painting Jews, wrestlers and peasants, as well as painting nudes and religious figures. Subverting the usual role of makeup, she painted her face with abstract designs and walked with her colleagues through the streets of Moscow in 1913 – a futurist manifestation and performance. She lived with Larionov without getting married. She wore trousers (unheard of for women at that time) when painting the sets for Sergei Diaghilev’s 1914 mime ballet production based on Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera-ballet, Le Coq d’or. That year she also starred in the first futurist film, Drama in the Futurists’ Cabaret No. 13, directed by Vladimir Kasianov. In 1915 she travelled to Switzerland where she worked on designs for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Sadly, she never returned to Russia. Living in Paris from 1919 onwards, she continued to work until her death: painting, designing sets and costumes for the ballet and theatre, producing schemes for interiors and creating clothing designs. Increasingly divorced from the French art world and cut off from her homeland, she fell into obscurity and has only gradually come to assume the position in art historical narratives that is rightfully hers.

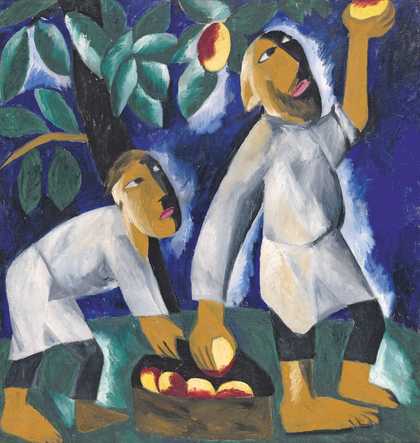

Natalia Goncharova

Gardening (1908)

Tate

Goncharova gained eminence as a painter, but she began her training as a sculptor at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture between 1901 and 1909. During the 1905 Russian Revolution, which radicalised the intelligentsia, the school acted as a refuge for political activists fighting the Tsarist autocracy on the streets of Moscow. Although Goncharova did not, as far as we know, belong to any radical political party, she and most of her fellow students sympathised with the revolutionaries. Not surprisingly, her subsequent works and actions, explicitly or implicitly, challenged the rules and expectations that the contemporary establishment imposed on her – both as an artist and as a woman.

She first came to prominence as a leader of the art movement known as neo-primitivism. Its goal was to create a quintessentially Russian art by fusing Western innovations of post-impressionism, fauvism and even proto-cubism with artistic devices derived from native artefacts such as the icon, the lubok (popular print), peasant embroideries and other elements of indigenous folk art. As a painting like Washing the Canvases 1910 (also known as Washing Linen) reveals, the impetus had come from France. Indeed, Goncharova acknowledged in the catalogue for her 1913 exhibition: ‘Modern French painters opened my eyes, and I grasped the great importance and value of the art of my native land, and through it, the value of the art of the East.’

Having grown up in the countryside, she was intimately acquainted with peasant culture and frequently wore peasant costume. Now, she used her knowledge to paint peasants at work. In Hay Cutting 1907 – 8 she employed the bold outlines, planar organisation, flat colour and disregard for perspective found in the popular prints or lubki. The large scyther dominates the composition, while the smaller figures carrying the hay complete the rural narrative. But Goncharova was no purist – all styles were grist to her mill. In Gardening 1908, she combined devices from East and West; the folds in the women’s clothes recall the treatment of drapery in icon painting, while the crystalline, stylised vegetation seems inspired by the lubki as well as by Henri Rousseau’s fanciful plants. For Peasants Picking Apples 1911, Goncharova employed a proto-cubist approach: the workers are huge, filling the canvas with their boldly faceted bodies and primitive, mask-like faces.

Natalia Goncharova, Peasants Picking Apples 1911, oil paint on canvas, 104.5 × 98 cm

State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Natalia Goncharova, Peasants Gathering Grapes 1913–14, oil paint on canvas, 145 × 130 cm

Bashkir State Art Museum, Ufa, © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Goncharova seems to have courted controversy by focusing on lowly members of society in works such as Wrestlers 1908–9 and Nude Black Woman 1911. It was especially true of her paintings of Jews, including Jews on the Street (A Jewish Shop) of 1912. Under the Tsars, Jews were second-class citizens, regularly persecuted and subject to mob violence. Her Old Man with Cat, also known as Monk with Cat or Rabbi with Cat 1911, outraged the political and religious establishment by depicting a Jew in an icon format.

It is difficult for the contemporary viewer to understand why Goncharova’s exploration of icon painting was so provocative. Paintings like Mother of God 1911 appear to be harmless homages to a great pictorial tradition. Nevertheless, in 1914 she was accused of blasphemy. The Evangelists of 1911 outraged the church. Although the work depicts the figures simply and with dignity, in a Cézannist hatching stroke, it challenged the traditional taboos against women painting icons and undermined accepted conventions against mixing sacred and profane imagery.

Natalia Goncharova, The Evangelists 1911, oil paint on canvas, 204 × 58 cm each

The State Russian Museum, St Petersburg, © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

This was not the first or only time that Goncharova infuriated the establishment. She was constantly defying conventions in accordance with her vow: ‘I set myself no limits in the sense of artistic achievements.’ In 1910, she was charged with displaying ‘corrupting pictures’ of nudes. Their angular articulation and chunky proportions might have offended accepted notions of good taste, and certainly challenged conventional notions of female beauty. In this respect, however, they differed little from the work exhibited by her male colleagues. Undoubtedly the main offence was that these works were produced by a woman, and so flouted established ideas of public decorum and the customary ban on women drawing live nudes. In A Model (Against a Blue Background) of 1909–10, the figure’s upper body (from her head to the pubic area) boldly confronts the viewer, filling the canvas, and challenging both academic and avant-garde practice. The ensuing trial focused on defining ‘public viewing’, the movement’s political orientation and Goncharova’s moral character. Such issues were closely connected in a society where the Academy was controlled by the Imperial household. Goncharova’s defence was creative freedom, but she was ultimately acquitted on the grounds that the works were shown at a private exhibition.

Natalia Goncharova, Cyclist 1913, oil paint on canvas, 79 × 105 cm

The State Russian Museum, St Petersburg, © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Natalia Goncharova, Dynamo Machine 1913, oil paint on canvas, 116 × 102 cm

Dendar Artworks Limited, © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Not surprisingly, Goncharova was among the first artists in Russia to respond to cubism and futurism, developing a style that became known as cubo-futurism, because it combined cubist fragmentation with a distinctly modern subject matter. Paintings such as Factory (Futurist) 1912, Weaving Loom + Woman (also known as The Weaver) and Cyclist (both of 1913), focus on the machines that were changing everyday life and people’s perceptions of reality. Cyclist depicts a male figure bent over the handlebars, peddling hard, bouncing over the cobbles of a provincial town and passing shop windows – the contents of which are fragmented to convey his dislocated impressions and a sensation of the speed at which he is travelling. Aeroplane over a Train, also of 1913, is a far more complex celebration of movement and speed. Since 1902 aircraft had literally given humanity wings and allowed people to transcend gravity. The painting evokes notions of time and the fourth dimension, conveying new perceptions of reality and sensations of a world in flux. Are the two forms of transport about to smash into each other or are they occupying the same space at different moments in time? At the intersection of the two structures, a single figure (ostensibly male) stands still, static amidst the chaos, acting as a pivot around which the composition moves. He may represent human ingenuity, which has set these forces in motion. Equally, he may be contemplating the wonders of technology and/or the disaster that may be unfolding as these two inventions collide. This is an image that can be interpreted in several different ways, perhaps reflecting Goncharova’s own ambivalent attitudes. After all, technological and industrial progress was transforming and improving everyday life in Russia, but at the same time also undermining traditional social structures, adversely affecting those rural crafts, culture and ways of life with which she identified and commemorated in her neo-primitivist works.

Natalia Goncharova

Rayonist Composition (c.1912–13)

Tate

Together with Larionov, Goncharova may also have been responsible for developing rayism (sometimes called rayonism – the French translation of the Russian term). Building on the achievements of futurism and cubism, this new style was not concerned with painting an object but instead focused on depicting the rays that were reflected from an object and the intersections of these rays in space. In exploring this idea, Goncharova produced abstract works like Rayonist Composition c.1912 –13. Although she continued to paint abstract canvases in the West, it was her colourful theatrical designs, based on the motifs of peasant embroideries, that caught the attention of the critics and the public’s imagination.

Throughout her career, Goncharova showed immense courage in fighting artistic and social conventions, pursuing artistic freedom, and rejecting traditional gender roles. She blazed a trail through all the obstacles in her path and produced an impressive body of innovative work that lay the aesthetic foundations for future developments.

Natalia Goncharova, Mystical Images of War: Angels and Aeroplanes 1914, lithograph on paper, 32.9 × 25.2 cm

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, © ADAGP Paris and DACS, London 2019

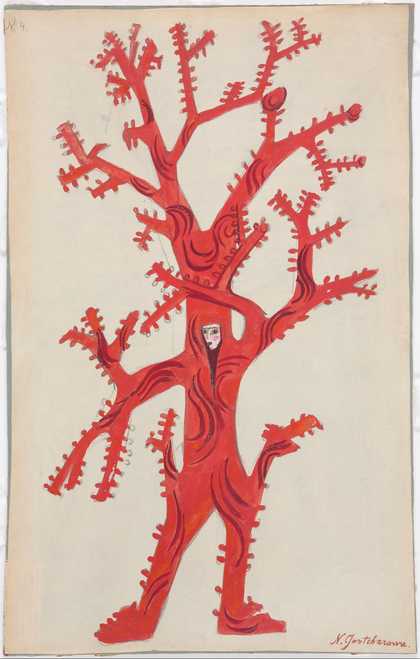

Natalia Goncharova, Coral. Costume design for Sadko 1915–16, gouache and graphite on paper mounted on cardboard, 37.5 × 23.9 cm

State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Natalia Goncharova, Design with birds and flowers. Study for textile design for House of Myrbor 1925–9, gouache and graphite on embossed paper, 74.5 × 67 cm

State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Natalia Goncharova, Orange Seller 1916, oil paint on canvas, 131 × 97 cm

Museum Ludwig, Cologne, © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Natalia Goncharova is presented in the Eyal Ofer Galleries, Tate Modern, 6 June – 8 September. Curated by Natalia Sidlina, Curator of International Art, and Matthew Gale, Head of Displays, with Katy Wan, Assistant Curator, Tate Modern. Supported by LetterOne, with additional support from Mr Petr Aven and Tate Members. The exhibition is organised by Tate Modern in collaboration with Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi, Florence and the Ateneum Art Museum, Helsinki.

Christina Lodder is Honorary Professor of History of Art, University of Kent.