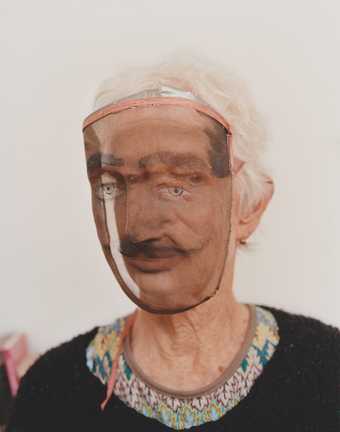

Dorothea Tanning at her home in the south of France, c.1955, photographed by Michael Ochs

Michael Ochs Archives / Stringer / Getty Images

Some years after Dorothea Tanning (1910–2012) left New York to move to Arizona with her lover Max Ernst, she sublet her flat to her friend Teeny, and her husband Marcel Duchamp. ‘One of the droll results of this,’ she writes in her autobiography, ‘was that for a time there were four names on our brass letterbox down in the little entrance vestibule’: Matisse (Teeny had previously been Mrs Pierre Matisse), Ernst, Duchamp, Tanning. She notes, parenthetically, ‘(When this amusing fact is reported – in books, the press – the last of the four names is omitted. After all, why not? In reports of this kind it is lustre that is required, not accuracy.)’ With the first UK retrospective devoted to Tanning’s work at Tate Modern, Tanning is finally receiving the kind of recognition that demonstrates how much her name deserved its place on that letterbox.

Born in Galesburg, Illinois in 1910, Dorothea Tanning was initially expected to become an actress; a series of photographs of her at age seven shows she had quite a flair for mugging and pulling faces: a born shape-shifter. But it was visual art that drew her, and she announced early on her intention to become a painter. When she was 15 she scandalised her parents by painting a naked woman with leaves instead of hair: they realised, to their horror, that their daughter was a ‘bohemian’. She always had a firm idea of what she wanted to do or explore, and she would not let anyone’s influence sway her. In art school, in Chicago, her teacher did not think much of her work; she speculates that this was because she was uninterested in depicting figures in the manner of all the other students, who were collapsing them into squat Picasso fertility totems. If Picasso was doing this, ‘I assumed he had his reasons. But I didn’t see why the rest of us should do the same thing.’

She would not be notably influenced by modern art until she encountered the surrealists. Attending the 1936–1937 Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Tanning would later describe it as an ‘explosion, rocking me on my run-over heels’, a ‘limitless expanse of possibility [that] … would possess me utterly’. She began to meet the surrealists as they arrived in the early 1940s, driven from Europe by fascism and war. ‘Shipwrecked surrealism’, as Tanning called it, was the toast of the town and Tanning and her American peers eagerly took it in.

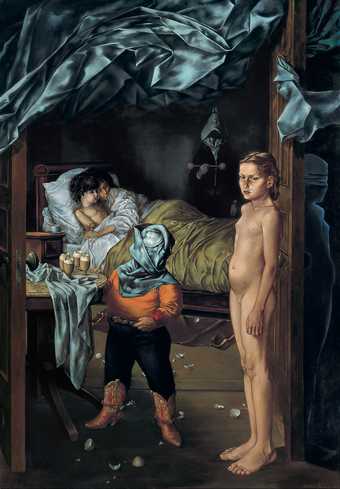

Dorothea Tanning

Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (1943)

Tate

Tanning’s early paintings, such as Birthday 1942, Children’s Games 1942, or Eine Kleine Nachtmusik 1943, all explore the liminal worlds between sleeping and dreaming, interior and exterior, childhood and maturity; they are fantastical, irrational and somehow give a feeling of being both methodically planned and spontaneously taking shape on the canvas. The dreaming girls of Eine Kleine Nachtmusik confront a large sunflower wilting on the landing, while their hair grows down to the floor or up towards the ceiling as if the whole scene were underwater; their dresses are open and in luxurious tatters; the landing offers several closed doors and one, cracked open and lit from inside, beckons temptingly as the tentacular arms of the sunflower threaten to encircle them. It is a painting about confrontation, Tanning would tell the art historian Victoria Carruthers, but the artist hints she’ll come out ahead: the dreaming girl grasps one of the flower’s petals firmly in her hand as she closes her eyes and tips her face up to the sunlight.

It was 1942’s Birthday, however, that would secure Tanning’s future. That year Peggy Guggenheim was organising an all-female exhibition for her gallery, Art of This Century. She sent her husband, Max Ernst, on a reconnaissance mission to young artists’ studios to see if he could unearth anything interesting. On a snowy day in 1942 he arrived at Dorothea’s door. They fell in love immediately and would be inseparable until Ernst’s death in 1976.

On that fateful studio visit, Ernst noticed Birthday on the easel, and recognised its brilliance. A woman identifiable as Tanning stands by a door, a winged lemur crouched at her bare feet. She wears a skirt made of roots that also somehow manages to recall a peacock’s tail feathers, its rhizomatic wildness echoed in the tendrils of her hair. Her purple and gold Shakespearean doublet lies open to reveal her bare torso; one of her hands emerges from a lace-trimmed sleeve to grasp at the doorknob of the closest door – is she arriving and closing the door behind her, or on her way out? Through the door opens a series of further doors.

There appear to be so many passages, and possibilities, open to her – and to us; we need only walk through them. But in her autobiography, Tanning puts us on our guard against these interpretations of her paintings: ‘A long time ago I said that I want to seduce by means of imperceptible passages from one reality to another … My wish: to make a trap (picture) with no exit at all either for you or for me.’ Her work must be looked at while in a state of movement, not in anticipation of arrival, for there is no way out. This does not symbolise that: this is en route to becoming that, or could take another path altogether, becoming something else entirely. It is their sense of kinetic energy that makes Tanning’s paintings stand out from the many surrealist fantastical creations.

Dorothea Tanning, The Guest Room 1950–2, oil paint on canvas, 152 × 106 cm

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018. Private collection, courtesy Malingue S.A., Paris, photo © Florent Chevrot

Dorothea Tanning

Some Roses and Their Phantoms (1952)

Tate

The year 1946 saw Tanning and Ernst flee their cramped quarters in New York (so many landings, so many doors) for the open expanses of Arizona and a house they would build themselves – one that ‘remained curiously unfinished in a way that never entirely left the desert outside’. Out west, ‘in that camera-sharp place where planetary upheaval had left its signature’ (as she described it), Tanning found she mainly wanted to paint interiors. Interior With Sudden Joy 1951, The Guest Room 1950–2, Some Roses and Their Phantoms 1952 all emerged from the hot desert, pursuing her visions of domestic reality as if intruded on by a gothic imaginary, and unconscious, supernatural forces.

Dorothea Tanning, Maternity 1946–7, oil paint on canvas, 142 × 121 cm

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018. Private collection

Dorothea Tanning, Maternity V 1980, oil paint on canvas, 40 × 50 cm

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018. Private collection

In 1946 Tanning also began a series of paintings called Maternity, of which the best-known is the first, showing a mother in tattered clothes holding a baby, while at her feet lies a most disturbing Pekingese with the face of a baby. In the desert beyond, through an open doorway, a distinctly uterine creature stands at attention. ‘I’m very much against the arrangement of procreation, at least for humans’, she wrote in her autobiography. ‘If I could have designed it, it would be a toss-up who gets pregnant, the man or woman.’ In the later canvases – Maternity III 1966 for instance – the figures are more abstract; it is difficult to say what is what in the tussling between almost-discernable woman and almost-discernible baby. There are, rather, suggestions of legs, hair, infant skulls. Mostly there is struggle.

Maternity III belongs firmly to the second period of Tanning’s career. After years of working in the surrealist vein, by the mid-1950s Tanning had tired of the movement’s standardising touch. ‘I began to chafe just a little at the reliance on precisely painted elements of the natural world in order to present an incongruity … Upon a vista of endless sand or in a bare room you could put anything. You could turn night into day and vice versa just by using light and dark colours. You would paint a sad giant dog (I did). Gradually, in looking at how many ways paint can flow onto canvas, I began to long for letting it have more freedom.’

Looking back, late in life, she would describe this as a ‘splintering’ of her canvases into ‘prismatic surfaces’. This work retains the dreamlike quality of her surrealist canvases but without the figurative precision of a representable world. Her thematic preoccupations were the same, but her formal interests had shifted. Colour became her primary mode – perhaps an unsurprising by-product of moving to the Sedona landscape with its radical blue skies and red rocks. She leaves the surrealist dreamscape behind in the wide-awake visions of Insomnias 1957, immense and imposing at 207 × 145 centimetres. A riot of lilac, yellow, purple and rust-red the colour of Sedona’s earth, the oil is so light in places as to resemble watercolours, and so insistently modelled and built-up in others it transcends its two dimensionality, verging on sculpture.

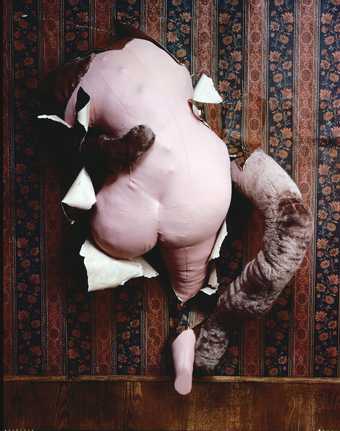

It’s telling that this ‘splintering’ happens just as Tanning and Ernst had to leave the United States, McCarthy-era legislation having deprived Ernst of his American citizenship. They moved back to France in 1957, where Tanning would remain until 1979, living between Huismes (a small town in the Loire Valley), Paris and Provence. Here she would push her work into an entirely new medium. In 1969, attending a performance of Stockhausen’s Hymnen at the Maison de la Radio in Paris, Tanning had another breakthrough. She saw, suddenly and clearly, the sculptures she would go on to make, ‘living materials becoming living sculptures’. Instead of paint and canvas, the new body of work would involve ‘carded wool and endless lengths of sensuous tweeds, the chopping up of which provided thrills of a kind very close to lust with its attendant peril’. She worked at her new everyday material until she had created ‘a family of sculptures that were the avatars, three-dimensional ones, of my two-dimensional painted universe’. An early example is Rainy Day Canapé 1970, ‘in which’, as one critic described, ‘a body appears to be struggling to birth itself from inside the upholstery of a couch’. Her wonderfully creepy Chambre 202, Hôtel du Pavot 1970–3 is a full-scale art installation, taking up a whole room; it’s like stepping into one of her early paintings, or the future scene of a crime.

Detail of Dorothea Tanning's Chambre 202, Hôtel du Pavot 1970–3

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018. Courtesy Centre Pompidou, Paris, musée national d'art moderne - centre de création industrielle

In her cloth sculptures, Tanning gives life to forms that have never existed before. This is still surrealism, but appropriated to suit ‘concerns both feminine and geriatric’, as Linda Nochlin has written of Tanning’s and Louise Bourgeois’s late soft sculptures. However, what Tanning resented more than anything else was a label. ‘Artist’s wife’, ‘surrealist’, ‘female painter’ – she rejected all the ways in which critics, no matter how well-intended, attempted to classify her. As she said in a 2002 interview, being called a surrealist made her feel ‘like a fossil’; she objected to her work being included in all-female shows for fear of its being ‘ghettoised’ there.

Her final act of shape-shifting was to change métiers, or at least to diversify them. Very late in life – in her eighties – she turned increasingly to language, writing poetry that she published in the Paris Review and the New Yorker as well as in two collections, and prose, in the form of a novel (Chasm, 2004) and a wildly romantic and charming autobiography (Between Lives, 2001). She died in 2012 at the age of 101, leaving us so many ways into her visions, so many imperceptible passages between realities. We have only to decide where to begin.

Dorothea Tanning, Tate Modern, 27 February – 9 June, curated by Alyce Mahon, Reader in Modern and Contemporary Art History, University of Cambridge and Ann Coxon, Curator, International Art, Tate Modern with Hannah Johnston, Assistant Curator, Tate Modern. Supported by The Destina Foundation, with additional support from the Dorothea Tanning Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council, Tate Patrons and Tate Members. Organised by the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid in collaboration with Tate Modern.

Lauren Elkin is a writer living in Paris. She is the author of Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice and London, published by Chatto & Windus. Her next book, Art Monsters, on women’s radical art from Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven to Pussy Riot, is forthcoming with Chatto & Windus.