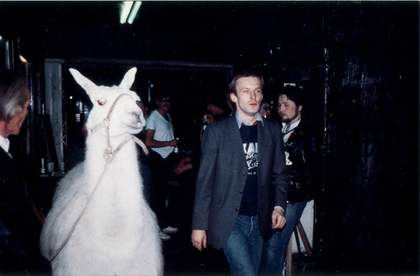

Franz West in 1990, photographed by Elfie Semotan

© Elfie Semotan

Austria’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, like the Burgtheater and Vienna State Opera, occupies a special place within the country’s high culture. More than an ordinary exhibition venue, it is a flagship. In his novel Old Masters (1985), Thomas Bernhard pushed this quality to the extreme, equating the institution with the country as a whole before launching into one of his infamous tirades: ‘the whole of this Austria, when all is said and done, is nothing but a Kunsthistorisches Museum, a Catholic-National-Socialist one, an appalling one ... A chaotic rubbish-heap, that is what today’s Austria is, this ridiculous pygmy state which drips with self-overestimation and which, 40 years after the so-called Second World War, has reached its absolute low only as a totally amputated state’. Museums have great merits, but Bernhard managed to give his comparison between state and museum a vitriolic quality.

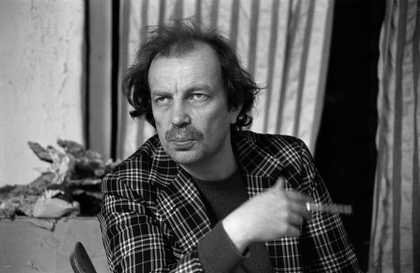

In the winter of 1989, four years after Old Masters was published and three years after the beginning of the ‘Waldheim affair’ (in which Austria’s president, Kurt Waldheim, was implicated in Nazi war crimes), which made headlines around the world, the Kunsthistorisches Museum hosted a well-received exhibition of works by the painter and sculptor Franz West, the first living artist ever to be shown there. In the museum’s Gemäldegalerie, West positioned 15 stripped-down metal couches, chairs and daybeds in front of the paintings by Velázquez and others, and invited museumgoers to sit or lie on them, thus becoming part of an artwork themselves. With his furniture pieces and later aluminium sculptures, writes curator Veit Loers, West’s focus from the outset ‘was not on autonomous artistic products, but rather on gentle interventions, surreal mises-en-scène within Austria’s then still authoritarian cultural landscape where art was assigned a specific role, kept in check wherever possible.’ The anti-image of a society in search of peace and quiet, sometimes to the point of dozing off, became visible. West often staged himself as part of this, having himself photographed as a reclining, resting or daydreaming artist – contemplation as part of artistic production.

Franz West posing on one of his metal couches at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, during Wiener Festwochen, 1990, photographed by Didi Sattmann

© Estate Franz West © Archiv Franz West, photo © 2018 Austrian Archives/Scala Florence

The artist, who the following year was invited by Hans Hollein to represent Austria at the Venice Biennale, was manifestly unfazed by his entry into the holiest of holies of national culture. ‘My works,’ West wrote in a text dated 1989, ‘correspond to the reusable coffins introduced by Josef II to save money (the appearance of an orderly burial was preserved while the corpse, having escaped the ambiguity of meaning, fell through a trapdoor into the grave). The items of furniture are skeletons – just as items of upholstered furniture have skeletons.’ The morbid quality of these remarks is reminiscent of ‘Wiener Schmäh’, a form of snarky humour cultivated in Vienna that is hard to define. For outsiders and the uninitiated, it often oversteps the line to blithe insult. Laughing at oneself and not taking oneself too seriously are certainly part of it. This sense of anarchy and the aesthetic associated with it is something West shared with peers like the German Martin Kippenberger and younger artists alike, including the Viennese Gelitin collective. There is also his obvious love of wordplay, as explored in the language experiments of the Vienna Group who circulated around the poet H.C. Artmann. In this light, the sculpture Deutscher Humor (German Humour) 1987 can be understood as exemplary, since the Germans are often said to have no sense of humour at all.

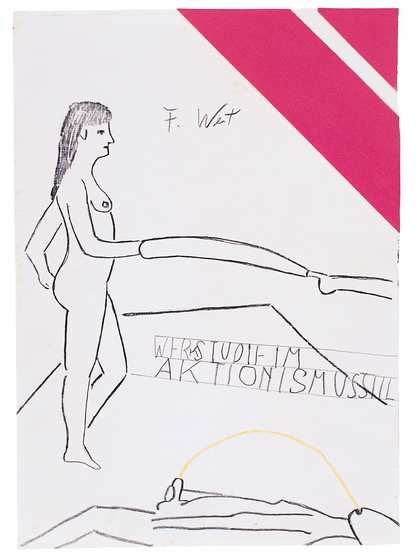

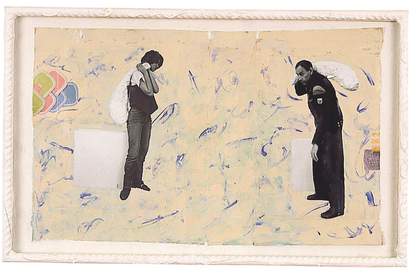

Franz West, Werkstudie im Aktionismusstil c.1974, pen and collage on paper, 21 × 15 cm

© Estate Franz West © Archiv Franz West

In contrast to the Vienna Actionists (Günter Brus, Otto Mühl, Hermann Nitsch, et al.) West did not deploy theatrical shock tactics that used existing body orifices or created new ones. Aged 16, he witnessed one of their performances and found it revolting (which, as a fellow artist, did not dampen his ongoing interest in the movement’s activities, however). His ‘drawings in Actionist taste’ from around 1974 reflect this distance underpinned by respect. But this did not mean he did not wish to work with the human body. West brought the body into the work indirectly, via his seats and couches, and via his peculiar Passstücke (most often translated as ‘Adaptives’, but also as ‘Fitting Pieces’ or ‘Adaptables’).

Franz West, Untitled 1990, collage and painted steel frame, 37.7 × 59 × 3 cm

© Estate Franz West © Archiv Franz West, courtesy Herbert Foundation, Ghent, photo: Wolfgang Woessner © DACS 2018

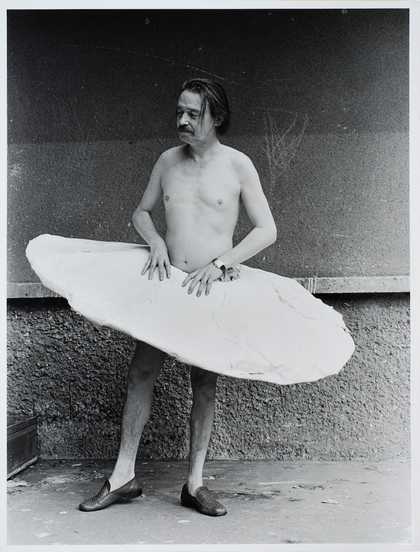

Otto Kobalek with Passstück by Franz West, Vienna, 1974, photographed by Friedl Kubelka

© Estate Franz West © Archiv Franz West, courtesy Galerie Raum mit Licht, photo © DACS 2018

Unlike his fellow artists – the avowedly left-wing sculptor Alfred Hrdlicka, for instance – West did not engage in public political debates. Instead, he insisted on the waywardness of art and the corresponding position of the artist. ‘West was not a political artist,’ says Christine Macel, curator-in-chief at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, ‘but his entire oeuvre revolves around the idea that art should be something one can literally interact with. West’s originality lies in the way he redefined the sculptural in relation to the body, to language, to the viewer.’

Franz West's Corona 2002 at Lake Zürich, 2006

© Estate Franz West © Archiv Franz West, courtesy Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zürich, photo: Stefan Altenbürger Photography, Zürich

Franz West's urinal sculpture Étude de couleur 1991 at Skulptur Projekte Münster, 1997

© Estate Franz West © Archiv Franz West, photo: Roman Mensing, artdoc.de

Franz West's Schlieren 2010 at Tate Modern, 2019

© Estate Franz West © Archiv Franz West, courtesy Zabludowicz Collection, London, photo © Tate / Matt Greenwood

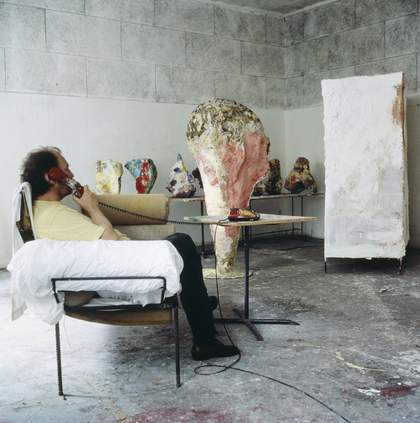

Between 1973 and the 2010s, he produced around 2000 sculptures. His art thus tends to appear as a paradoxical mix of gentle refusal and high productivity. The way he stuck to the unwieldy, dirty, crooked and imperfect, or to papier-mâché as a material, can be read as a formula of resistance to the ossifying forces and refining tendencies that start to take effect, seemingly by natural law, whenever an artist’s career reaches a certain degree of international prominence. Such strategies of refusal have found their secret manifesto in the short story ‘Bartleby, the Scrivener’ by Herman Melville: ‘I would prefer not to.’ Here, art is made possible by the passive activity of resting, which also applies to the moment and its fleeting quality: ‘The perception of art,’ as West said of one of his couches, ‘takes place through the pressure points that develop when you lie on it.’ On the other hand, West engaged heavily in a range of collaborative activities with artists like Heimo Zobernig and Bernhard Riff, or integrated others’ work into his displays, as in the installation Viennoiserie 1998, which brings together works by artists including Raymond Pettibon, Paul McCarthy and Joseph Kosuth in a kind of salon hang and interior situation.

Franz West

Viennoiserie (1998)

Tate

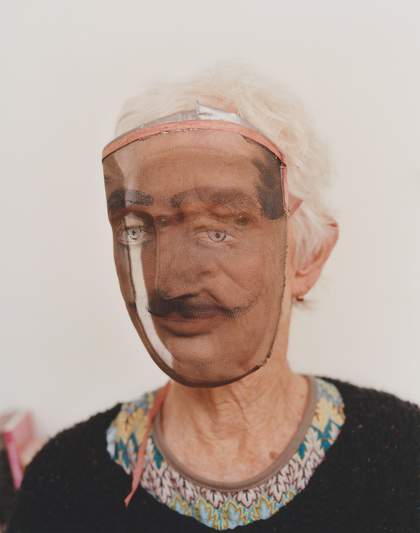

Franz West in his studio in Vienna, 1995

© Estate Franz West © Archiv Franz West, courtesy David Zwirner

Visiting a major museum or wandering around a biennial looking at art all day long can be an exhausting thing to do. Thus, giving the audience the chance to rest or even take a nap might be understood as a special form of artistic generosity. And it is certainly no coincidence that later versions of West’s reclining furniture – such as the 72 ‘divans’ in the open-air cinema at documenta IX in 1992 – recall, with their Oriental throw rugs and bolsters, the famous couch of the Viennese psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, now to be found in London, the city to which its owner emigrated in 1938. As well as being a symbol for Freud’s theories of dreams and for speaking about sex, repressed fantasies and mental trauma, it has also become the place where the modern mind comes to itself.

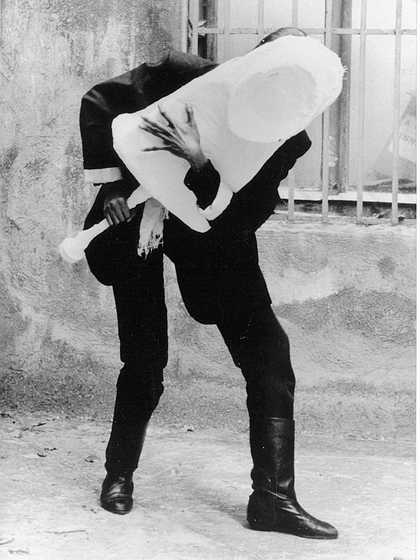

Lisa de Cohen with Passstück by Franz West, Vienna, 1983, photographed by Rudolf Polanszky

© Estate Franz West © Archiv Franz West

West’s Passstücke have also inspired psychoanalytical interpretations, which, in the beginning at least, were supported by corresponding statements from the artist. In an early text, co-written with the poet Reinhard Priessnitz for the invitation card to an exhibition at Galerie nächst St Stephan in 1980, the objects are described as ‘constituting a potential attempt to give shape to neurotic symptoms (the basis of culture according to Freud)’. Elsewhere, West explained: ‘If neuroses could be perceived visually, they would look like Passstücke.’ Later, however, West distanced himself from Freud and let it be known that he rejected his theory of drives, the idea in psychoanalysis that biological instincts lie behind our behaviours.

The eating of certain types of food requires a specific form of routine or skill, but there hardly seems to be an ‘elegant’ way of using Passstücke. West began producing them in the mid-1970s in the apartment of his mother, Emilie, who worked as a dentist. Her practice and the apartment were located in Karl-Marx-Hof, one of the best-known municipal housing projects in Vienna, referred to, on account of its striking architecture and size, as ‘the workers’ Versailles’. His mother’s assistant, a former set builder, taught West the papier-mâché technique that he went on to use in most of his sculptures.

Franz West, Passstück 1983, wood, paint, cardboard, adhesive, fabric, plaster and metal, 45 × 45 × 29.5 cm

© Estate Franz West © Archiv Franz West, private collection courtesy Peder Lund, photo: Lukas Schaller

Franz West, Passstück 1983/2007 (painted by Eugenia Rochas), wood, paint, gauze and plaster, 11.5 × 79.5 × 22.5 cm

© Estate Franz West © Archiv Franz West, private collection courtesy Peder Lund, photo: Lukas Schaller

Bulky and hard to balance, the Passstücke are the opposite of ergonomic designs or the kind of smooth-surfaced objects said to comfort via tactile contact. Touching a Passstück, one is immediately surprised by its weight. It takes a while to become even moderately accustomed to these strange, plaster-white forms: their structure and the distribution of weight across the object remain confusing. Handling the Passstücke prompts slapstick movements or contortions. These are artworks that are activated only by being ‘used’. At Kasper König’s request, West showed his Passstücke in the Westkunst exhibition of 1981 (an ambitious 10,000-square-metre blockbuster exhibition that underlined Cologne’s aspirations to serve as the European powerhouse of Western contemporary art). König recalls that the invitation to handle the objects was at first only accepted by a few people: ‘His sloping furniture resembled foreign bodies, and his Passstücke seemed eerie and even embarrassing to the majority of visitors to the exhibition. The open offer to use these objects was hardly even taken up, and then mainly by artists.’ This may be one reason why West presented them together with photographs and videos demonstrating their usage. Over the course of his life as an artist, they mutated into a kind of artistic trademark, allowing his anarchic humour and artistic independence to be experienced directly. All you have to do is pick them up.

Franz West, Reinhard Bernsteiner, Herbert Flois and Songül Boyraz posing with Passstücke outside the artist's studio in Vienna, 2007, photographed by Lukas Schaller

© Estate Franz West © Archiv Franz West, photo © Lukas Schaller

Franz West, Tate Modern, 20 February – 2 June, curated by Mark Godfrey, Senior Curator, International Art (Europe and the Americas), Tate Modern and Christine Macel, Chief Curator, Centre Pompidou with Monika Bayer-Wermuth, Assistant Curator, Tate Modern and Loïc Le Gall, Assistant Curator and Luise Willer, Researcher at Centre Pompidou. Supported by Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne, with additional support from the Franz West Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council and Tate Patrons. Organised by Tate Modern and the Centre Pompidou, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris.

Kito Nedo lives in Berlin where he works as a freelance journalist for several magazines and newspapers. In 2017, he won the ADKV-ART COLOGNE Award for Art Criticism. This text has been translated from German by Nicholas Grindell.