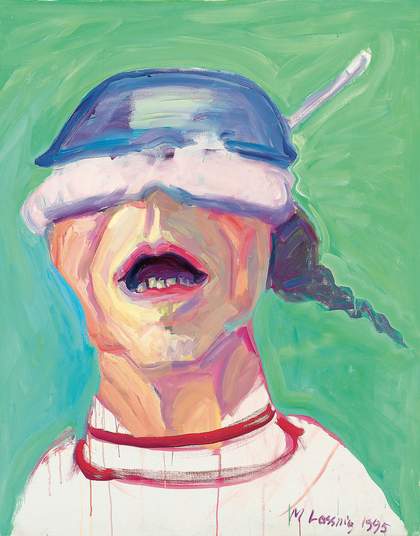

Maria Lassnig, Self-Portrait with Saucepan 1995, oil on canvas, 125 x 100 cm

© Maria Lassnig Foundation

In 1972 a curious awards ceremony took place in the cramped Manhattan studio of Austrian painter Maria Lassnig. Tired of being ignored as an artist in her homeland, she had moved to New York in 1968 at the age of 49. Four years later, the Austrian government finally corrected its oversight and chose her as its national Artist Laureate. Uneasily sipping champagne from plastic glasses, her hippyish downtown artist friends watched as a few Austrian officials, stiffly dressed in business suits, honoured Lassnig in her modestly furnished loft, crowning her with a laurel wreath – a misplaced and absurdly formal ritual later described by one embarrassed guest as hilarious.

For most of her life, Maria Lassnig worked in obscurity. In 1980 she was offered a teaching position at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna – a role she accepted only when she ensured that her salary matched that of Joseph Beuys – and, at the venerable age of 60, became the first-ever female professor of painting in the German-speaking world. She died aged 94 in 2014, the year she was awarded the Venice Biennale’s Golden Lion Lifetime Achievement Award.

Maria Lassnig, Self-Portrait with Stick 1971, oil and charcoal on canvas, 193 x 129 cm

© Maria Lassnig Foundation

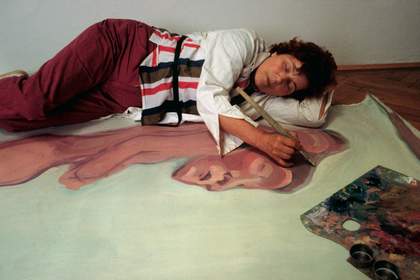

Maria Lassnig painting in her studio in Vienna, 1983, photographed by Michael Westermann

photo © Kurt-Michael Westermann/Maria Lassnig Foundation

Lassnig devoted her life to what she termed ‘body awareness painting’: portraying not how the body looks, but how it feels to be inside one. In her effort to capture bodily experience – its flaws, functions, gestures and moods – she sometimes worked lying down alongside the canvas, or leaning against it, even sitting on it. She never worked from photographs, but relied solely on inner sensations, sometimes closing her eyes while painting. ‘The hardest thing is really to concentrate on the feeling while drawing. Not drawing a rear-end because you know what it looks like, but drawing the rear-end feeling.’ Her painting Hospital 2005 presents a row of half-naked aching bodies, their exposed state instantly bringing to mind those awful back-to-front, neck-tied hospital gowns that leave their wearers worryingly unprotected from behind. That queasy emotional cocktail – vulnerability, powerlessness, fear – was the mainstay of Lassnig’s art.

Maria Lassnig, Hospital 2005, oil on canvas, 150 x 200 cm

© Maria Lassnig Foundation

‘Embarrassment is a challenge. I want to paint things that are uncomfortable,’ the artist said. Her uneasy figures – such as the cowering creature in The Believers and Honest Believers 2002, sitting atop a stool in his pointy dunce cap, glaring at us in unfriendly horror – are rendered in acidic, poisonous shades. Greens are bluish; reds are greenish; yellows purplish. Hers are discomforting and unstable shades, as indefinable in colour as a bruise. A trio of multi-hued figures – one pinky-green, another fire-engine red, the third a bloodless white – comprise the cast of 3 Ways of Being 2004: a line-up of pug-nosed, pin-headed, rat-tailed, pot-bellied, armless characters. Mouths are especially noxious, sometimes missing teeth (The Admiration 2008), or, as in Photography against Painting 2005, displaying hideous giant gnashers and a thick red tongue, hanging wetly like a bloodied slug.

Embarrassment is a uniquely human phenomenon, mysteriously conjoining body and mind. Our awareness of having exposed ourselves to ridicule prompts an uncontrolled physical response: we sweat, fidget, tremble and blanch. We quiver, fumble, twist our fingers and lower our eyes – all actions inventoried in Lassnig’s canvases. ‘Why should the thought that others are thinking about us affect our capillary circulation?’ asked Charles Darwin in 1872’s The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals, a question the eminent natural scientist never managed to answer. Actions that are acceptable in private can turn embarrassing if witnessed by others. Indeed, Lassnig’s people seem perpetually caught in some unseemly act: retrieving something from a lover’s nose; playing football without trousers; conversing with a pet hamster.

Maria Lassnig, Two Ways of Being (Double Self-Portrait) 2000, oil on canvas, 100 x 125 cm

© Maria Lassnig Foundation

Like art itself, embarrassment requires being seen. Perhaps for this reason Lassnig pays so much attention to the eyes. They are enlarged, crooked, bloodshot and bulging. They are too close; too far apart; mismatched; lost in shadow. Eyes are disembodied and dangled overhead. They protrude like a frog’s, stare emptily like a bird’s. They come in standard-issue pairs but also singularly, such as the twisted cyclops of The Innocent Glance 2008. The word embarrass derives, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, from the French embarrasser: to block, hamper or impede. Indeed, sight in Lassnig’s figures is often blocked: eyes are veiled, pierced, shut tight, masked, encased and blindfolded. Particularly in the late works, they can be erased altogether. However, the absence of any background means the figures inhabiting her canvases are always in plain view: she offers them nowhere to hide from us their candid display of human imperfection.

Not all of Lassnig’s figures are pathetic. The undressed older woman sitting astride a motorcycle in Country Girl 2001 affects a certain narcissistic bravado. The waltzing skeleton and his partner in Death and the Girl 1999 seem not to notice us at all, absorbed by a silent music. Emotions in her art range from desire, joy and curiosity to disappointment, injury and desperation. None the less, the gnawing feeling of embarrassment – prompted by our wayward physical bodies, our crippling emotional frailty – predominates. In My teddy is more real than me 2002, a naked woman who looks remarkably like the artist (many of Lassnig’s people resemble her, and she is a ruthless self-portraitist) cuddles an oversized teddy bear. The woman’s skin is green and she looks mortified, as if we’d rudely surprised her in this compromising position.

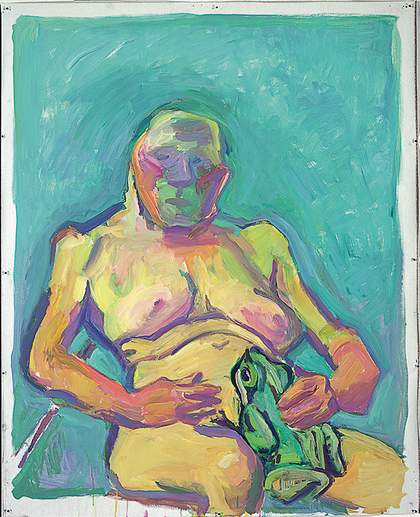

Maria Lassnig, Frog Princess 2000, oil on canvas, 125 x 100 cm

Zabludowicz Collection, © Maria Lassnig Foundation

Martin go in the corner, shame on you is the title of Martin Kippenberger’s 1989 standing statue, a dejected figure facing the wall and banished – rather than installed – in the gallery corner. Kippenberger admired Lassnig’s art, and his awkward figures borrow heavily from her. Both artists developed a kind of soul-baring self-portraiture that verged on confession, but Kippenberger’s public shame is guiltier than Lassnig’s. Where the latter’s lonely figures whisper ‘Look at me; I did something bad,’ Kippenberger’s cry ‘Look at me! I am bad!’ Lassnig’s on-canvas trangressions are usually minor, but discomfort levels rise in a painting featuring a middle-aged man attempting some ungodly act on a doll-like figure, unreassuringly titled Bugbear 2001. Frog Princess 2000 shows a woman pressing a frog against her genitals, while the unapologetic cook in The Madonna of the Pastries 2001 has mischievously replaced the newly-wed figurines atop a freshly baked wedding cake with a pair of dripping hypodermic needles.

Lassnig’s art is often compared with the colourful work of young American painters Dana Schutz and Amy Sillman, but she can also recall German-born Jutta Koether. Best known as an abstract painter, in 2009 Koether gave a performance at the Reena Spaulings gallery in New York titled The Staging of Restricted Means in the Landscape Redefines the Terms of Pleasure of Painting. Ostensibly a lecture about her painting practice, the performance grows acutely embarrassing as the artist acts out her incoherent socio-artistic aspirations. She stomps clumsily around the gallery, fiddles with the lights, drops her notes, then crouches on the floor in the desperate attempt to reassemble them. Finally, Koether begins to shout the lyrics of Garbage Man, by the punk band The Cramps. As the performance shifts from boring to ‘excruciating’ – as one audience member described it – we are reminded of Lassnig’s film Cantata 1992, her self-deprecating autobiography, jauntily set to music. At one point the Austrian artist similarly turns punk, sporting goth make-up and a studded leather jacket while smoking a fag. In their pursuit of the embarrassing, both Koether and Lassnig have intuited that a middle- aged wannabe punk rocker, singing tunelessly about artistic frustration, is a guaranteed cringe trigger.

Still from Maria Lassnig’s film Cantata 1992

© Maria Lassnig Foundation

Ever since Jackson Pollock danced around his barn dripping paint, the medium of painting has offered tormented artists the ideal outlet to release their angst messily: a wildly splattered canvas willingly serves as emotional playpen. Despite being laden with emotion, Lassnig’s works share none of the abstract expressionists’ reckless abandon. In fact, they are figurative, controlled, expertly draughted and precisely coloured. (A classically trained painter, she excels at such painterly moments as expressive hand gestures, accurately foreshortened figure groups, convincing drapery and pitch-perfect light and shadow.) Conceptual art-making predominated during much of her artistic lifetime, when painting itself was deemed embarrassing, and many figurative artists of the period – from Philip Guston to Carroll Dunham – adopted, like Lassnig, a cartoonish style. As with them, her body shapes are unnaturally distorted and tinted, yet weirdly alive and familiar: perhaps we recognise their humanity by virtue of their telltale embarrassment.

In Erving Goffman’s Embarrassment and Social Organization of 1956, the sociologist theorised that human interaction depends on the unspoken imperative that we all go to great pains to avoid embarrassment. And yet, as Michael Craig-Martin has written: ‘To be an artist, you have to make yourself vulnerable in exactly the ways most people spend their lives trying to avoid.’ Are artists exempt from Goffman’s social contract? For most of us, embarrassment is an undesirable presentation of the self, to be avoided at any cost. The exasperating force of Lassnig’s art is that she elects embarrassment, doggedly pursuing its sensations and giving them shape thanks to her precise draughtsmanship and virtuoso painting technique, preserving her fears on the canvas forever.