Poet, engraver, painter, seer, William Blake was a flop in his lifetime. Nearly two centuries after his death, he is still a confounding figure. But whatever you may think of him – crank, undiagnosed nutter, or prophet – the man was a grafter, you have to give him that; even on his deathbed he was still working.

On his last day, he set aside his illustrations for Dante’s Divine Comedy, looked upon his wife Catherine, and cried out: ‘Stay Kate. Keep just as you are – I will draw your portrait – for you have ever been an angel to me.’ Catherine, the illiterate daughter of a market gardener, hadn’t been just a faithful companion to him, but also a working partner in full sympathy with Blake’s visionary outlook, as much as his craft. Anyone familiar with the seer of Soho will know that in calling Catherine an angel, he wasn’t simply indulging in a figure of speech: this was a man who’d been seeing and speaking with celestials since boyhood.

William Blake, Catherine Blake c.1805, graphite on paper, 28.6 x 22.1 cm

Courtesy Tate Photography

It’s said that after completing Catherine’s portrait, Blake downed tools for good and spent his last hours singing verses and hymns until he expired. Sadly, that late portrait is now lost, but Tate has in its collection an unfinished drawing from earlier days, Catherine Blake c.1805. In a room full of rarely displayed engravings, watercolours and drawings, this partial rendering of Mrs Blake is striking for its tenderness and calm. To see it unframed and up close is a rare treat.

Blake was a man much given to visions. His watercolours in particular have the hectic quality of fever dreams. In his underworld images for Dante’s Divine Comedy, or his famous, acid-trip-like painting, The Ghost of a Flea c.1819–20, there is little echo of the poet’s enduring claim that ‘all that lives is holy’. But in his drawing of his beloved, there’s a stillness and precision born of a quality of attention that feels like reverence. ‘As a man is,’ the painter once said, ‘so he sees.’

Blake has caught his wife at work. Her head is down, her hands obscure, and there is the suggestion that she is at her embroidery, or – more likely, given their modest circumstances – busy darning. Her hair is wrapped in a scarf, but a few feral curls escape. Almost everything about the drawing is faint and provisional, except for the details of the face; this is where Blake’s hand is firm and his line strongest. Catherine’s nose is robust, her mouth full. The erotic violence of the painter’s visionary and mythological scenes is tamped down here, but this is no chaste or idealised vision of womanhood: Catherine appears as a maker and worker. Up close you can see the sensual detail in the delicate rendering of her eyelashes. To me, it speaks not merely of adoration, but also admiration.

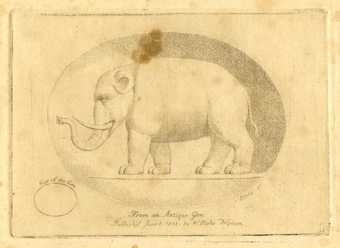

The paper on which the portrait is drawn tells a deeper story still. Catherine’s figure is embossed because the page is recycled; Blake has drawn her on the back of a bit of work – a verse from a charming sentimental poem about an elephant by William Hayley. The gentleman poet Hayley was a generous fellow, but a man of conventional outlook, and, although he was keen to see Blake prosper, he couldn’t help but try to tame the painter’s wild genius. Blake later wrote: ‘Thy Friendship oft has made my heart to ache: Do be my Enemy for Friendship’s sake.’ Anyone curious enough to look up Blake’s illustrations for Hayley’s Ballads Founded on Anecdotes Relating to Animals will note that this particular pachyderm has the feet of a badly upholstered moggy. The artist was either ‘phoning it in’, or he’d never seen an elephant in his life. The difference between the gig work and the portrait is in the quality of attention.

William Blake's print illustrating William Hayley's animal ballad The Elephant, published by Blake in 1802

In any case, the painter’s frustration at being co-opted by the establishment cost him his patronage. His contempt for hack work is every bit as luminous as his love for Catherine. She bears the force of the former, and wears the latter in the lightness of her husband’s line, sacred and profane all in the one lasting moment.

Catherine Blake can be viewed by appointment at Tate Britain's Prints and Drawings Room. The Blake Room and William Blake's Legacy 1920s–1980s, both curated by Martin Myrone, are at Tate Britain.

Tim Winton is a writer. His book The Boy Behind the Curtain: Notes from an Australian Life is published by Picador.