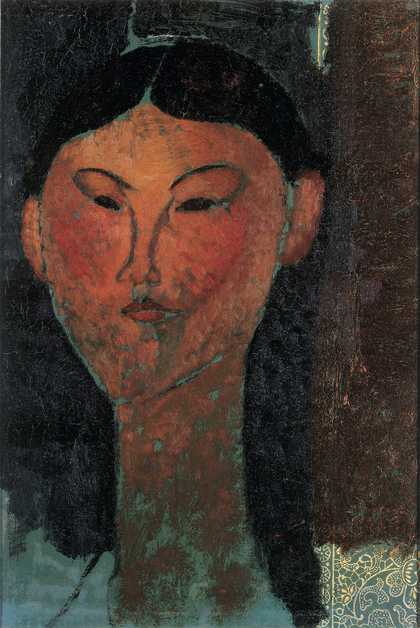

Beatrice Hastings in Paris, 1918

Courtesy HPB Library, Toronto

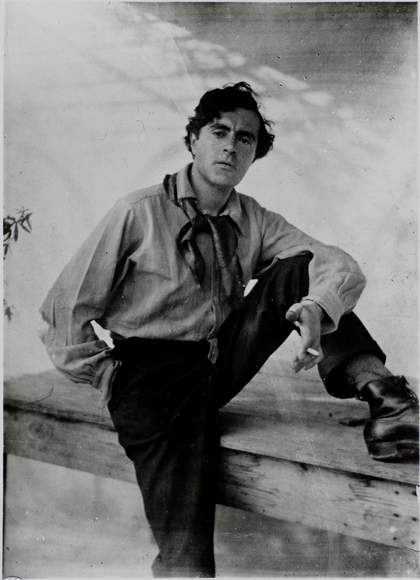

Amedeo Modigliani, 1909

Courtesy Getty Images/The LIFE Picture Collection

Amedeo Modigliani’s artwork depicts few objects and even fewer landscapes. Occasionally, a door or an item of furniture establishes an interior, but most often the only narrative is the inner drama supplied by a face, the position of the hands, the tilt of a head. Early paintings depicted caryatids, but these were soon freed from their architecture and given something more abstract to support. Charged with a dormant theatricality, his figures often resemble marionettes at rest.

Modigliani (1884–1920) initially intended to be a sculptor. Inspired and encouraged by Brancusi, he started carving heads from stone, but ill health and money troubles soon led him to abandon the medium. Dust from the stone irritated his lungs and fits of coughing due to childhood tuberculosis sabotaged the steady hand; during the First World War marble became scarce and stone rose in price. He would change medium, but not style, replicating in paint the angularity of his three-dimensional figures.

Among the portraits Modigliani painted in his short lifetime, the least puppet-like were perhaps those of Beatrice Hastings, his partner from 1914 to 1916. In the two years of their stormy, brawl-filled romance, he painted her 14 times. For Modigliani, the two years with Hastings saw a surge in focus and creativity, and coincided with his return to painting. For Hastings too, their time together marked one of her most sustained productive periods.

‘She had as many faces as voices. Modigliani's portraits together convey a shape-shifting, highly volatile nature’

From their very first encounter, Modigliani was drawn to the English writer, referred to in Paris as ‘la poétesse anglaise’. As a devoted reader of Dante, he was also seduced by Beatrice’s name. Poets already featured in his life, and he’d painted them all: three years earlier, he’d had a romance with the melancholy Russian Anna Akhmatova; his drinking companion was novelist and poet Blaise Cendrars; and he knew the French writers Max Jacob and Jean Cocteau. By most accounts, he was never without a book in his pocket, usually Lautréamont’s baroquely audacious narrative prose poem Les Chants de Maldoror. As for Hastings, her first impression was far from romantic: ‘a pig and a pearl ... he looked ugly, ferocious, greedy’. Yet he improved upon second encounter, elevated from pig to ‘pale and ravishing villain’.

Amedeo Modigliani Béatrice (Portrait de Béatrice Hastings) 1916, Oil on canvas with newsprint, BF361, The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Even within the bohemian milieu of Paris in the 1910s, Hastings and Modigliani made a feral, wayward pair. He lived in a haze of intoxication – absinthe, wine, hashish – and would dance on tabletops, howl out lines of Italian verse, and rampage through the streets at night. Hastings, meanwhile, extravagant in dress and occasionally accessorised with a basket of live ducks as a handbag, had forged a reputation as one of the main voices of The New Age, a British socialist journal of art and politics whose publisher, AR Orage, had been her partner for seven years. (Contemporaries considered their set the dark avant-garde or, in Virginia Woolf’s words, ‘the literary underworld’.) Hastings’s affairs with New Zealand author Katherine Mansfield and the writer and painter Wyndham Lewis contributed to her eventual split from Orage, and in 1914 she moved to Paris as the journal’s correspondent. There she embarked on a series of chronicles entitled ‘Impressions of Paris’. Through Max Jacob, she rapidly gained entry into artistic circles, and soon formed part of what Malcolm Bradbury would call ‘the standing British atelier population in Paris who became points of contact and transmission’.

By this time Hastings had already published under a wide spectrum of pen names. ‘Beatrice Tina’ was the poet who often drew on mythological themes (most famously, in the poem The Lost Bacchante) and an outspoken champion of the suffrage movement. In bold contrast was the essayist ‘D Triformis’, a detractor of the suffragettes and of Beatrice Tina herself. ‘TKL’, meanwhile, was a critic who parodied art movements, and quarrelled publicly with Ezra Pound while penning a parody of Marinetti’s futurist manifesto. ‘Alice Morning’ was the Paris diarist (and her most developed and consistent voice). At other moments she was ‘Pagan’, ‘Cynicus’, ‘Robert à Field’, ‘Mrs Malaprop’ or ‘G Whiz’. When a persona became troublesome, she would shed it and create a new one. Encompassing them all was ‘Beatrice Hastings’ – itself the pseudonym of Emily Alice Beatrice Haigh, born in England in 1879 and raised in South Africa. After a falling out with her family and a brief marriage to a boxer, she returned to Europe in time for modernism’s heyday.

Amedeo Modigliani, Beatrice Hastings 1915, oil paint on paper, 40 x 28.5 cm

Private Collection

She had as many faces as voices. Modigliani’s portraits together convey a shape-shifting, highly volatile nature: here, she stands on the threshold of a doorway, birdlike, with an inordinately long neck and a plume tucked behind her ear; there, she sits in the mesh of a gilt armchair, shadows rising off her like a headdress. She is hatted or unhatted; glimpsed frontal, profile or three quarters; dressed in dark reds, oranges and umber. Her face is sometimes lean, more often round and strong-chinned. In one portrait, she is clad in a pale blue, checked shirt with white collar, her pointy, doll face and fluted lips strikingly similar to Modigliani’s Pierrot (Self-Portrait as Pierrot) 1915. Elsewhere, she is Madame Pompadour, the rim of her black feathered hat sailing across her forehead. In another portrait she looks precariously stitched up, as if, with one tug of the thread, her whole being might unravel, her absent eye like the missing button of a worn, over-loved toy.

Their domestic world was agitated, yet creatively ablaze; the outside world was rocked by war. Often Hastings and Modigliani would wake to the thunder of bombs. During the winter siege they visited the soup kitchens, along with many other starving artists. The tone of Hastings’s dispatches from Paris darkened from light-hearted cultural chronicles to more serious reportage. After nearly two years the couple parted ways, beset by rows, affairs, and Beatrice’s growing love of whiskey.

In early 1920, Modigliani’s tuberculosis came roaring back and he died, destitute, aged 35. Back in England, Hastings continued to write, albeit in more isolated conditions. The year Modigliani passed away, her own health worsened and she entered a clinic. A journal, later published as Madame Six, interweaves her Paris reminiscences – never far – with details of her hospital routine. Man Ray’s photograph of her from 1922 depicts a gloomy character: jaw clenched, gaze sad and evasive, all self-possession and serenity gone from the face.

Amedeo Modigliani, Madam Pompadour 1915, oil paint on canvas, 61 x 50 cm

The Art Institute of Chicago

Her interest in theosophy deepened, particularly her devotion to the medium Madame Blavatsky, in her eyes a kindred spirit, and of whom in 1937 she published an impassioned defence: ‘Civilised woman wants something more than to be the means to man’s life: she wants to live herself.’ Despite doing her best to honour this credo, Hastings ultimately faded into obscurity, ending her days in fevered, fragile solitude. In 1943, she gassed herself in a small house in Worthing, in the south of England, a pet mouse cradled in her hand. Her death hardly earned a mention in the press, apart from the local paper.

Hastings’s final Paris persona was 'Minnie Pinnikin', the eponymous narrator of an unfinished novella in which she detailed her relationship with Modigliani. Pinnikin – the name a portmanteau, possibly, of pinnacle and mannequin – captured the moment in her life when Hastings found herself at the peak of her craft, while existing as the central model in someone else’s.

Modigliani is at Tate Modern, 23 November – 2 April 2018.

Chloe Aridjis is a London-based writer. Her first novel, Book of Clouds, won the French Prix du Premier Roman Etranger. Her second novel, Asunder, is set in the National Gallery and her third, Sea Monsters, is due for publication in spring 2018. She was guest curator of the Leonora Carrington exhibition at Tate Liverpool.